| Library / Biographies |

Adi Śaṅkara Biography

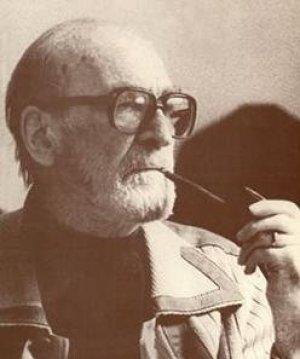

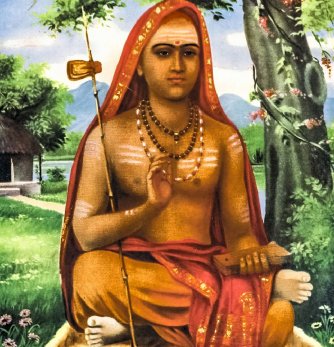

Adi Śaṅkara was a famous Hindu theologian, founding the school of Advaita Vedānta. ![]() Adi Śaṅkarācārya (आदि शङ्कराचार्य) was an Indian philosopher and theologian who consolidated the doctrine of Advaita Vedānta.

Adi Śaṅkarācārya (आदि शङ्कराचार्य) was an Indian philosopher and theologian who consolidated the doctrine of Advaita Vedānta.

He is credited with unifying and establishing the main currents of thought in Hinduism.

The Sringeri records state that Śaṅkara was born in the 14th year of the reign of "VikramAditya", but it is unclear as to which king this name refers. Though some researchers identify the name with Chandragupta II (4th century CE), modern scholarship accepts the Vikramaditya as being from the Chalukya dynasty of Badami, most likely Vikramaditya II (733–746 CE),

Several different dates have been proposed for Śaṅkara:

• 509–477 BCE: This dating is based on records of the heads of the Shankara's cardinal institutions Maṭhas. The exact dates of birth of Adi Shankaracharya believed by four monasteries are Dvārakā at 491 BCE, Jyotirmath at 485 BCE, Jagannatha Puri at 484 BCE and Sringeri at 483 BCE., while according to the Kanchi Peetham Adi Shankara was born in Kali 2593 (509 BCE). The successive heads of the Kanchi and all other major Hindu Advaita tradition monasteries have been called Śaṅkarācārya leading to some confusion, discrepancies and scholarly disputes. The chronology stated in Kanchi matha texts recognizes five major Śaṅkaras: Adi, Kripa, Ujjvala, Muka and Abhinava. According to the Kanchi matha tradition, it is "Abhinava Śaṅkara" that western scholarship recognizes as the Advaita scholar Śaṅkara, while the monastery continues to recognize its 509 BCE chronology.

• 44–12 BCE: the commentator Anandagiri believed he was born at Chidambaram in 44 BCE and died in 12 BCE.

• 6th century CE: Telang placed him in this century. Sir R.G. Bhandarkar believed he was born in 680 CE.

• c. 700 – c. 750 CE: Late 20th-century and early 21st-century scholarship tends to place Śaṅkara’s life of 32 years in the first half of the 8th century. According to the Indologist and Asian Religions scholar John Koller, there is considerable controversy regarding the dates of Śaṅkara – widely regarded as one of India's greatest thinkers, and "the best recent scholarship argues that he was born in 700 and died in 750 CE".

• 788–820 CE: This was proposed by early 20th-century scholars and was customarily accepted by scholars such as Max Müller, Macdonell, Pathok, Deussen and Radhakrishna. The date 788–820 is also among those considered acceptable by Swami Tapasyananda, though he raises several questions. Though the 788–820 CE dates are widespread in 20th-century publications, recent scholarship has questioned the 788–820 CE dates.

• 805–897 CE: Venkiteswara not only places Śaṅkara later than most, but also had the opinion that it would not have been possible for him to have achieved all the works apportioned to him, and has him live ninety two years.

The popularly accepted dating places Śaṅkara to be a scholar from the first half of the 8th century CE.

Śaṅkara was born in the southern Indian state of Kerala, according to the oldest biographies, in a village named Kaladi sometimes spelled as Kalati or Karati. He was born to Nambudiri Brahmin parents.

His parents were an aged, childless, couple who led a devout life of service to the poor. They named their child Śaṅkara, meaning "giver of prosperity". His father died while Śaṅkara was very young. Śaṅkara’s upanayanam, the initiation into student-life, had to be delayed due to the death of his father, and was then performed by his mother.

Śaṅkara’s hagiography describe him as someone who was attracted to the life of Sannyasa (hermit) from early childhood. His mother disapproved.

A story, found in all hagiographies, describe Śaṅkara at age eight going to a river with his mother, Sivataraka, to bathe, and where he is caught by a crocodile. Śaṅkara called out to his mother to give him permission to become a Sannyasin or else the crocodile will kill him.

The mother agrees, Śaṅkara is freed and leaves his home for education. He reaches a Saivite sanctuary along a river in a north-central state of India, and becomes the disciple of a teacher named Govinda Bhagavatpada.

The stories in various hagiographies diverge in details about the first meeting between Śaṅkara and his Guru, where they met, as well as what happened later. Several texts suggest Śaṅkara schooling with Govindapada happened along the river Narmada in Omkareshwar, a few place it along river Ganges in Kashi (Varanasi) as well as Badari (Badrinath in the Himalayas).

The biographies vary in their description of where he went, who he met and debated and many other details of his life. Most mention Śaṅkara studying the Vedas, Upanishads and Brahmasūtra with Govindapada, and Śaṅkara authoring several key works in his youth, while he was studying with his teacher. It is with his teacher Govinda, that Śaṅkara studied Gauḍapādiya Kārika, as Govinda was himself taught by Gauḍapāda.

Most also mention a meeting with scholars of the Mimamsa school of Hinduism namely Kumarila and Prabhakara, as well as Mandana and various Buddhists, in Shastrarth (an Indian tradition of public philosophical debates attended by large number of people, sometimes with royalty).

Thereafter, the biographies about Śaṅkara vary significantly. Different and widely inconsistent accounts of his life include diverse journeys, pilgrimages, public debates, installation of yantras and lingas, as well as the founding of monastic centers in north, east, west and south India.

While the details and chronology vary, most biographies mention that Śaṅkara traveled widely within India, Gujarat to Bengal, and participating in public philosophical debates with different orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy, as well as heterodox traditions such as Buddhists, Jains, Arhatas, Saugatas, and Carvakas.

During his tours, he is credited with starting several Matha (monasteries). Ten monastic orders in different parts of India are generally attributed to Śaṅkara’s travel-inspired Sannyasin schools, each with Advaita notions, of which four have continued in his tradition: Bharati (Sringeri), Sarasvati (Kanchi), Tirtha and Asramin (Dvaraka).

Other monasteries that record Śaṅkara’s visit include Giri, Puri, Vana, Aranya, Parvata and Sagara – all names traceable to Ashrama system in Hinduism and Vedic literature.

Śaṅkara had a number of disciple scholars during his travels, including Padmapada (also called Sanandana, associated with the text Atma-bodha), Sureshvara, Tothaka, Citsukha, Prthividhara, Cidvilasayati, Bodhendra, Brahmendra, Sadananda and others, who authored their own literature on Śaṅkara and Advaita Vedānta.

Adi Śaṅkara is believed to have died aged 32, at Kedarnath in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand, a Hindu pilgrimage site in the Himalayas.

Texts say that he was last seen by his disciples behind the Kedarnath temple, walking in the Himalayas until he was not traced. Some texts locate his death in alternate locations such as Kanchipuram (Tamil Nadu) and somewhere in the state of Kerala.

Works of Adi Śaṅkarācārya

Bhāṣya (commentaries) on:

• Brahmasūtra

• Aitareya Upaniṣad (Rigveda)

• Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (Śukla Yajurveda)

• Īśa Upaniṣad (Śukla Yajurveda)

• Taittirīya Upaniṣad (Kṛṣṇa Yajurveda)

• Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad (Kṛṣṇa Yajurveda)

• Kaṭha Upaniṣad (Kṛṣṇa Yajurveda)

• Kena Upaniṣad (samaveda)

• Chāndogya Upaniṣad (samaveda)

• Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad (Atharvaveda) and Gauḍapāda Kārika

• Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad (Atharvaveda)

• Praśna Upaniṣad (Atharvaveda)

• Bhagavadgītā (Mahābhārata)

• Vishnu Sahasranama (Mahābhārata)

• Sānatsujātiya (Mahābhārata)

• Gāyatrī Mantraṃ

Prakaraṇa grantha (treatises):

• Vivekacūḍāmaṇi (Crest-Jewel of Wisdom)

• Upadeśasāhasri (A thousand teachings)

• Śataśloki

• Daśaśloki

• Ekaśloki

• Pañcīkaraṇa

• Ātma bodha

• Aparokṣānubhūti

• Sādhana Pañcakaṃ

• Nirvāṇa Ṣaṭkam

• Manīśa Pañcakaṃ

• Yati Pañcakaṃ

• Vākyasudha (Dṛg-Dṛśya-Viveka)

• Tattva bodha

• Vākya vṛtti

• Siddhānta Tattva Vindu

• Nirguṇa Mānasa Pūja

• Prasnottara Ratna Malika (The Gem-Garland of Questions and Answers)

• prabodhasudhakara

• svatma prakasika

Stotra (hymns):

• Ganesha Pancharatnam

• Annapurnashtakam

• Kalabhairavashtakam

• Dakshinamurthy Stotram

• Krishnashtakam

• Bhaja Govindaṃ, also known as Mohamuḍgara

• Śivānandalahari

• Saundaryalahari

• Jeevanmuktanandalahari

• Śrī Lakṣmīnṛsiṃha Karāvalamba Stotraṃ

• Śāradā Bhujangaṃ

• Kanakadhāra Stotraṃ

• Bhavāni Aṣṭakaṃ

• Śiva Mānasa Pūja

• Pandurangashtakam

• Subramanya Bhujangam

• Kashi Panchakam

• Suvarnamala

• Mahishasura Mardini stotram

• Meenakshi Pancha Ratnam

• Nirvana Shatakam also known as Atma Shatakam

• Sabarigiri Ashtakam

Published Works

Collections

• Sri Śaṅkara Granthavali - Complete Works of Sri Śaṅkaracarya in the original Sanskrit, v. 1-10, revised ed., Samata Books, Madras, 1998

• Sankaracaryera Granthamala, v. 1-4, Basumati Sahitya Mandira, Calcutta, 1995.

• Upanishad-bhashya-sangraha, Mahesanusandhana Samsthanam, Mt. Abu, 1979-1986. Śaṅkara's bhashyas on the Katha, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Chandogya and Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

• Prakarana-dvadasi, Mahesanusandhana Samsthanam, Mt. Abu, 1981. A collection of twelve prakarana granthas.

• A Bouquet of Nondual Texts, by Adi Śaṅkara, Translated by Dr. H. Ramamoorthy and Nome, Society of Abidance in Truth, 2006. A collection of eight texts. This volume contains the Sanskrit original, transliteration, word-for-word meaning and alternative meanings, and complete English verses.

• Svatmanirupanam: The True Definition of One's Own Self, Translated by Dr. H. Ramamoorthy and Nome, Society of Abidance in Truth, 2002.

• Nirguna Manasa Puja: Worship of the Attributeless One in the Mind, Translated by Dr. H. Ramamoorthy and Nome, Society of Abidance in Truth, 1993.

• Hastamalakiyam: A Fruit in the Hand or A Work by Hastamalaka, Translated by Dr. H. Ramamoorthy and Nome, Society of Abidance in Truth, 2017.

Brahmasutra Bhashya

• Edited with Marathi translation, by Kasinath Sastri Lele, Srikrishna Mudranalaya, Wai, 1908.

• Edited with vaiyasika-nyayamala of Bharatitirtha, and Marathi commentary, by Vishnu Vaman Bapat Sastri, Pune, 1923.

• Selections translated into English, by S. K. Belvalkar, Poona Oriental Series no. 13, Bilvakunja, Pune, 1938.

• Edited with Adhikarana-ratnamala of Bharatitirtha, Sri Venkatesvara Mudranalaya, Bombay, 1944.

• Translated into English, by V. M. Apte, Popular Book Depot, Bombay, 1960.

• Translated into English, by George Thibaut, Dover, New York, 1962. (reprint of Clarendon Press editions of The Sacred Books of the East v.34, 38)

• Sri Śaṅkarācārya Granthavali, no. 3, 1964.

• Translated into English, by Swami Gambhirananda, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata, 1965.

• Translated into German, by Paul Deussen, G. Olms, Hildesheim, 1966.

Bhagavadgita Bhashya

• Critically edited by Dinkar Vishnu Gokhale, Oriental Book Agency, Pune, 1931.

• Edited with Anandagiri's Tika, by Kasinath Sastri Agashe, Anandasrama, Pune, 1970.

• Alladi Mahadeva Sastri, The Bhagavad Gita : with the commentary of Sri Śaṅkarācārya, Samata Books, Madras, 1977.

• A. G. Krishna Warrier, Srimad Bhagavad Gita Bhashya of Sri Śaṅkarācārya, Ramakrishna Math, Madras, 1983.

• Translated into English, by Swami Gambhirananda, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata, 1984.

• Trevor Leggett, Realization of the Supreme Self : the Bhagavad Gita Yogas, (translation of Śaṅkara's commentary), Kegan Paul International, London, 1995.

Upadeśasāhasri (A Thousand Teachings)

• Sitarama Mahadeva Phadke, Śaṅkarācāryakrta Upadesashasri, Rasikaranjana Grantha Prasaraka Mandali, Pune, 1911. (with Marathi translation)

• Paul Hacker, Unterweisung in der All-Einheits-Lehre der Inder: Gadyaprabandha, (German translation of and notes on the Prose book of the upadeSasAhasrI) L. Röhrscheid, Bonn, 1949.

Vivekacūḍāmaṇi (Advaita introductory treatise)

• Edited with English translation, by Mohini Chatterjee, Theosophical Publishing House, Madras, 1947.

• Ernest Wood, The Pinnacle of Indian Thought, Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton (Illinois), 1967. (English translation)

• Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood, Śaṅkara’s Crest-jewel of Discrimination, with A Garland of Questions and Answers, Vedānta Press, California, 1971.

• Sri Śaṅkara's Vivekachudamani with an English translation of the Sanskrit Commentary of Sri Chandrashekhara Bharati of Sringeri. Translated by P. Śaṅkaranarayanan. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1999.

Pañcīkaraṇa1

• Edited with Sureshvara's varttika and varttikabharana of Abhinavanarayanendra Sarasvati (17th century), Sri Vani Vilas Press, Srirangam, 1970.

• Edited with Gujarati translation and notes, Sri Harihara Pustakalya, Surat, 1970.

Sources

• https://en.wikipedia.org/

Footnotes

1. Pañcīkaraṇa (five-fold) is the method and process of the subtle matter (or the prior stage of matter) to transform itself into gross matter. Intelligence is the subtle manifestation of consciousness and matter its gross manifestation. Adi Śaṅkara treatise on this theory was elaborated by his disciple Sureshvaracharya, and later on commented upon in 2400 slokas by Ramananda Saraswati, disciple of Ramabhadra, and in 160 slokas by Ananda Giri, disciple of Suddhananda Yati.