| News / Science News |

Anxiety molecules affect male and female mice differently

Feeling worried from time to time is normal. But for people with anxiety disorders, fear and uncertainty interfere with everyday activities. The chance of developing certain emotional and social disorders can vary depending on your sex. Women, for instance, are 60% more likely than men to experience an anxiety disorder over their lifetimes.

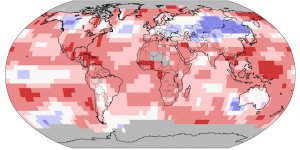

Brain cells (shown in red) activated by the “social hormone” oxytocin prompt differences in how male and female mice behave. ![]()

Individual differences in how you behave or feel can be caused by a variety of factors, including how your brain is wired or the hormones in your body. Oxytocin is a hormone that plays a role in social behavior, but can also help regulate stress and anxiety.

A team of researchers previously discovered a group of oxytocin-responsive brain cells—called oxytocin receptor interneurons—that regulate a social behavior in female mice.

The scientists activated oxytocin receptor interneurons and then compared how anxious or social the mice were during different tasks. The team measured the animals’ behaviors while they explored an open field or an elevated maze or while in a chamber with an unfamiliar mouse of the opposite sex.

After the brain cells were activated, male mice became less anxious but the females did not. The female animals did, however, become more social.

The light-activated brain cells project into 2 areas of the medial prefrontal cortex―a brain region responsible for complex behaviors. In male mice, cells in one of the areas responded more robustly to the light activation. Cells in this region were also more sensitive in male animals to a stress hormone called CRH.

That oxytocin receptor interneurons released a molecule called CRHBP that blocked the activity of CRH. CRHBP thus reduced the stress hormone’s effect on cells in the male brain. Female mice had higher levels of CRH in their brains. This likely accounts for their lack of sensitivity to CRHBP’s stress-reducing effects.

Stress, social situations, and sex-related differences can affect how much oxytocin and CRH is present in different brain areas. The authors suggest that the balance between oxytocin and CRH levels may be what determines the differences in behavior. (NIH)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE