| News / Science News |

Debris piles up in ‘mid-ocean garbage patches’

Researchers in Germany and the US explored plastic waste pathways, moving from the coasts to the middle of the oceans, to determine the relative strengths of different subtropical gyres in the oceans and their role in the long-term accumulation of debris. They say their findings will help target ocean clean-up programmes.

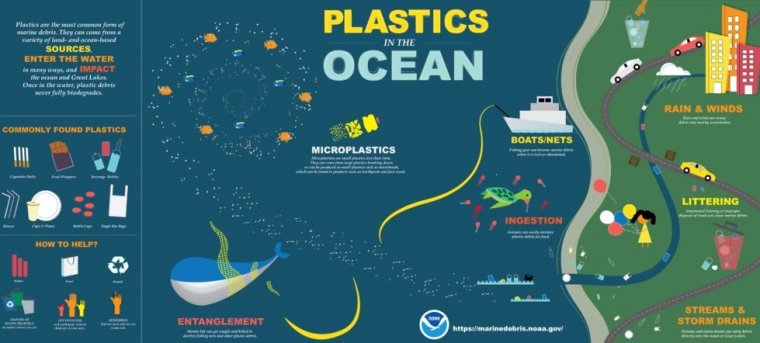

Plastics in the ocean. Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris Program

A gyre is a system of large, rotating ocean currents that also have become synonymous with concentrations of plastic waste and debris that are transported by ocean currents. The main gyres are the subtropical gyres of the North and South Pacific, the North and South Atlantic, and the Indian Ocean. According to a 2020 Pew Trusts report, an estimated 11 million metric tonnes of plastic waste enter the oceans annually.

Philippe Miron, scientist at the University of Miami and an author of the study published March in Chaos, says they explored debris pathways and patch stability by quantifying the connection between them and their ability to retain trash. They found that gyres, in general, are weakly connected or disconnected from each other.

“The weakness of the Indian Ocean gyre as a plastic debris trap is consistent with transition paths not converging within the gyre,” Miron says. “Indeed, in the event of anomalously intense winds, a subtropical gyre is more likely to export garbage toward the coastlines than into another gyre,” Miron says.

“We identified a high-probability transition channel connecting the Great Pacific Garbage Patch with the coasts of eastern Asia, which suggests an important source of plastic pollution there,” Miron tells.

One of the biggest discoveries the group made is that while the North Pacific subtropical gyre attracts the most debris, consistent with earlier assessments, the South Pacific gyre stands out as the most enduring, because debris has fewer pathways out and into other gyres.

“Our results, including prospects for garbage patches yet to be directly or robustly observed, namely in the Gulf of Guinea and in the Bay of Bengal, have implications for ocean cleanup activities,” says Miron. “The reactive pollution routes we found provide targets — aside from the great garbage patches themselves — for those cleanup efforts.”

Many paths starting from coastal region of the Indian Ocean end up in the South Pacific gyre and the South Atlantic gyre in general, the garbage patches are disconnected from each other but the three garbage patches in the Southern Hemisphere are more linked together than with the patches in the Northern Hemisphere.”

“Because debris tend to fragment and sink when at sea for extended period, we believe that the reactive pollution routes provide targets (alternatives to the great garbage patches themselves) for activities such as ocean cleanup,” says Miron. (SciDev.Net)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE