| Health / Health News |

Four-stranded DNA structures found to play role in breast cancer

Four stranded DNA structures – known as G-quadruplexes – have been shown to play a role in certain types of breast cancer for the first time, providing a potential new target for personalised medicine, say scientists at the University of Cambridge.

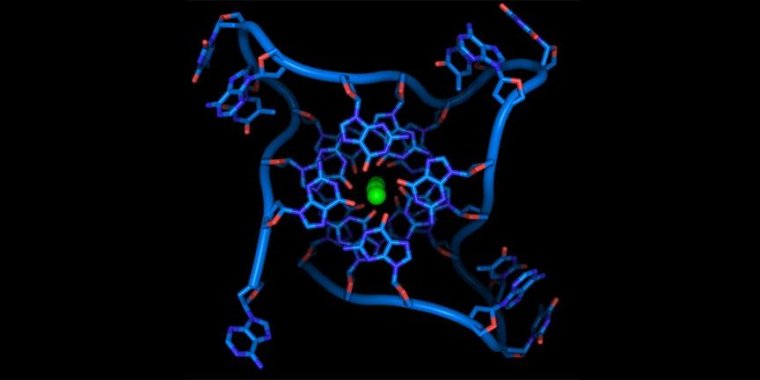

Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. The DNA strand (blue) circles the bases that stack together in the center around three co-ordinated metal ions (green). Photo: Thomas Splettstoesser

In 1953, Cambridge researchers Francis Crick and James Watson co-authored a study which showed that DNA in our cells has an intertwined, ‘double helix’ structure.

Sixty years later, a team led by Professor Sir Shankar Balasubramanian and Professor Steve Jackson, also at Cambridge, found that an unusual four-stranded configuration of DNA can occur across the human genome in living cells.

These structures form in regions of DNA that are rich in one of its building blocks, guanine (G), when a single strand of the double-stranded DNA loops out and doubles back on itself, forming a four-stranded ‘handle’ in the genome. As a result, these structures are called G-quadruplexes.

Professor Balasubramanian and colleagues have previously developed sequencing technologies and approaches capable of detecting G-quadruplexes in DNA and in chromatin (a substance comprised of DNA and proteins).

They have previously shown that G-quadruplexes play a role in transcription, a key step in reading the genetic code and creating proteins from DNA.

Crucially, their work also showed that G-quadruplexes are more likely to occur in genes of cells that are rapidly dividing, such as cancer cells.

Now, for the first time, the team has discovered where G-quadruplexes form in preserved tumour tissue/biopsies of breast cancer.

During the process of DNA replication and cell division that occurs in cancer, large regions of the genome can be erroneously duplicated several times leading to so-called copy number aberrations (CNAs).

The researchers found that G-quadruplexes are prevalent within these CNAs, particularly within genes and genetic regions that play an active role in transcription and hence in driving the tumour’s growth.

Professor Balasubramanian said: “We’re all familiar with the idea of DNA’s two-stranded, double helix structure, but over the past decade it’s become increasingly clear that DNA can also exist in four-stranded structures and that these play an important role in human biology. They are found in particularly high levels in cells that are rapidly dividing, such as cancer cells. This study is the first time that we’ve found them in breast cancer cells.”

There are thought to be at least 11 subtypes of breast cancer, and the team found that each has a different pattern – or ‘landscape’ – of G-quadruplexes that is unique to the transcriptional programmes driving that particular subtype.

Professor Carlos Caldas from the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, said: “While we often think of breast cancer as one disease, there are actually at least 11 known subtypes, each of which may respond in different ways to different drugs.

“Identifying a tumour’s particular pattern of G-quadruplexes could help us pinpoint a woman’s breast cancer subtype, enabling us to offer her a more personalised, targeted treatment.”

By targeting the G-quadruplexes with synthetic molecules, it may be possible to prevent cells from replicating their DNA and so block cell division, halting the runaway cell proliferation at the root of cancer.

The team identified two such molecules – one known as pyridostatin and a second compound, CX-5461, which has previously been tested in a phase I trial against BRCA2-deficient breast cancer. (University of Cambridge)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE