| News / Science News |

Global human genome study reveals our complex evolutionary history

Uncovering a large amount of previously undescribed genetic variation, a new study provides new insights into our evolutionary past, and highlights the complexity of the process through which our ancestors diversified, migrated and mixed throughout the world.

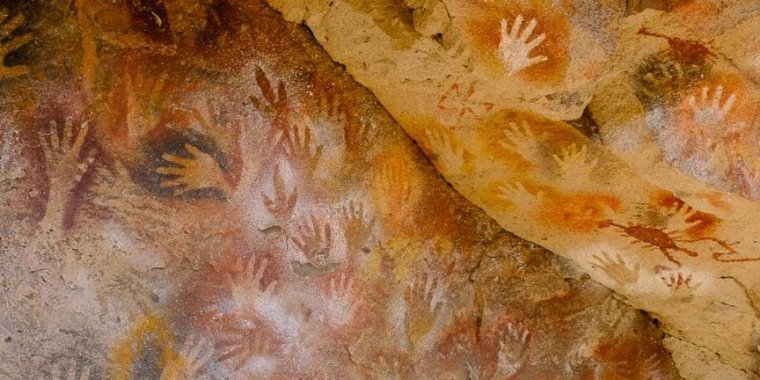

Handprints in the Cueva de las Manos, Patagonia, made by hunter-gatherers around 9,000 years ago. Photo: Matt Midgley

Uncovering a large amount of previously undescribed genetic variation, the study provides new insights into our evolutionary past, and highlights the complexity of the process through which our ancestors diversified, migrated and mixed throughout the world.

It is the first to apply the latest high-quality sequencing technology to such a large and diverse set of humans, covering 929 genomes from 54 geographically, linguistically and culturally diverse populations from across the globe.

The results provide unprecedented detail of our genetic history, and highlights how it is characterised by multiple layers of complexity. Although genetic differences between populations reflect their diversity, many patterns are shared across continents, revealing both ancient and recent connections between populations.

Researchers in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Genetics analysed the sequencing data to investigate evidence of interbreeding between the ancestors of modern humans and extinct human lineages such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, which occurred 40,000 to 60,000 years ago.

They found evidence that the Neanderthal ancestry of modern humans can be explained by just one major ‘mixing event’, most likely involving several Neanderthal individuals coming into contact with modern humans shortly after the latter had expanded out of Africa.

"Studying the patterns of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans hints at the structure of human communities more than 50,000 years ago. It is remarkable that patterns of Neanderthal ancestry are so similar in populations around the world today, and may have derived from a single Neanderthal population," said Dr Aylwyn Scally, a researcher in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Genetics.

In contrast, several different sets of DNA segments inherited from Denisovans were identified in people from Oceania and East Asia, suggesting at least two distinct mixing events. This could suggest that multiple small groups of Denisovans once lived in different regions of Asia.

Until recently, it was thought that only people outside sub-Saharan Africa had Neanderthal DNA. Now, the discovery of small amounts of Neanderthal DNA in west African people is most likely to reflect genetic backflow into Africa from Eurasia.

The consensus view of human history is that the ancestors of present-day humans diverged from the ancestors of extinct Neanderthal and Denisovan groups around 500,000-700,000 years ago, before the emergence of ‘modern’ humans in Africa in the last few hundred thousand years.

Around 50,000-70,000 years ago, some humans expanded out of Africa and soon after mixed with archaic Eurasian groups. After that, populations grew rapidly, with extensive migration and mixture as many groups transitioned from hunter-gatherers to food producers over the last 10,000 years.

The team found millions of previously unknown DNA variations that are exclusive to one continental or major geographical region.

Though most of these were rare, they included common variations in certain African and Oceanian populations that had not been identified by previous studies – variations that may influence the susceptibility of different populations to disease.

Medical genetics studies have so far predominantly been conducted in populations of European ancestry, meaning that any medical implications that these variants might have are not known.

Identifying these novel variants represents a first step towards fully expanding the study of genomics to underrepresented populations.

However, no single DNA variation was found to be present in 100 per cent of genomes from any major geographical region while being absent from all other regions.

This finding underlines that the majority of common genetic variation is found across the globe. (University of Cambridge)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE