| News / Science News |

Gut research identifies key cellular changes associated with childhood-onset Crohn’s Disease

Scientists have tracked the very early stages of human foetal gut development in incredible detail, and found specific cell functions that appear to be reactivated in the gut of children with Crohn’s Disease.

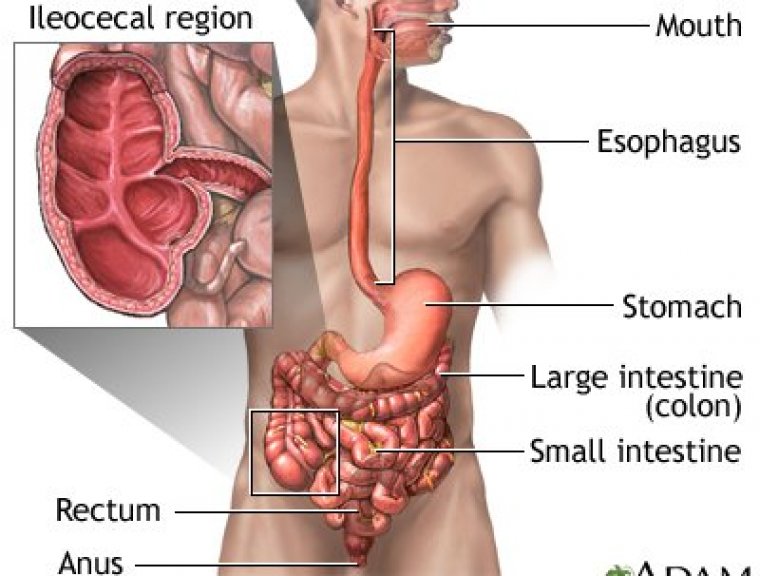

Crohn disease - affected areas. Photo: U.S. National Library of Medicine

Crohn’s Disease is a type of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Incidence has increased dramatically in recent decades, especially in children - who can suffer very aggressive symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhoea and fatigue.

This lifelong condition can have major life implications; the cause is not understood, treatments often don’t work, and there is no cure.

“Crohn’s Disease can be particularly aggressive and more treatment-resistant in children, so there’s a real need to understand the condition when it affects them and perhaps come up with childhood-specific treatments,” said Dr Matthias Zilbauer in the Department of Paediatrics at the University of Cambridge.

The researchers used a cutting-edge technology called single-cell RNA sequencing to look at gene expression in individual cells of the developing human gut, six to ten weeks after conception.

They focused on the inner lining of the gut, called the intestinal epithelium, and found that the cells there divide constantly at this early stage, guided by messages from other cell types. This allows the gut to grow and form the structures needed for good gut function later in life.

Tissues from the guts of children with Crohn’s Disease, aged between four and twelve, were also analysed. The study revealed that some of the cellular pathways active in the epithelium of the foetal gut appear to be reactivated in Crohn’s Disease. These pathways were not active in healthy children of a similar age.

“Our results indicate there might be a reprogramming of specific gut cell functions in Crohn’s Disease. We don’t know whether this is the cause of the disease or a consequence of it, but either way it is an exciting step in helping us to better understand the condition,” said Zilbauer.

The findings shed light on fundamental molecular mechanisms of human gut development. The team also found that lab-grown ‘mini-guts’ undergo similar individual cellular changes to those inside a developing foetus.

This implies that lab-grown models are a powerful and accurate tool for future research into very early gut development and associated diseases.

“This study is part of the international Human Cell Atlas effort to create a ‘Google map’ of the entire human body. With single-cell RNA sequencing we can look at any tissue and identify the individual cell types it’s made up of, the function of those cells, and even identify new cell types,” said Dr Sarah Teichmann at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, and co-chair of the Human Cell Atlas Organising Committee, whose expertise enabled analysis of the huge amount of data generated by this technique.

She added: “A complex tissue like the gut contains different cell types, and these ‘talk’ to each other - the function of one cell affects the function of another. That’s particularly important in the early stages of gut development, and something we can interrogate using computational analyses of single cell RNA sequencing data.” (University of Cambridge)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE