| Library / Literary Works |

The Jewelled Arrow

In the city of Vardhamana in India there lived a powerful king named Vira-Bhuja, who, as was the custom in his native land, had many wives, each of whom had several sons.

Of all his wives this king loved best the one named Guna-Vara, and of all his sons her youngest-born, called Sringa-Bhuja, was his favourite. Guna-Vara was not only very beautiful but very good. She was so patient that nothing could make her angry, so unselfish that she always thought of others before herself, and so wise that she was able to understand how others were feeling, however different their natures were from her own.

Sringa-Bhuja, the son of Guna-Vara, resembled his mother in her beauty and her unselfishness; he was also very strong and very clever, whilst his brothers were quite unlike him. They wanted to have everything their own way, and they were very jealous indeed of their father's love for him. They were always trying to do him harm, and though they often quarrelled amongst themselves, they would band together to try and hurt him.

It was very much the same with the king's wives. They hated Guna-Vara, because their husband loved her more than he did them, and they constantly came to him with stories they had made up of the wicked things she had done.

Amongst other things they told the king that Guna-Vara did not really love him but cared more for some one else than she did for him. The most bitter of all against her was the wife called Ayasolekha, who was cunning enough to know what sort of tale the king was likely to believe.

The very fact that Vira-Bhuja loved Guna-Vara so deeply made him more ready to think that perhaps after all she did not return his affection, and he longed to find out the truth. So he in his turn made up a story, thinking by its means to find out how she felt for him. He therefore went one day to her private apartments, and having sent all her attendants away, he told her he had some very sad news for her which he had heard from his chief astrologer.

Astrologers, you know, are wise men, who are supposed to be able to read the secrets of the stars, and learn from them things which are hidden from ordinary human beings. Guna-Vara therefore did not doubt that what her husband was about to tell her was true, and she listened eagerly, her heart beating very fast in her fear that some trouble was coming to those she loved.

Great indeed was her sorrow and surprise, when Vira-Bhuja went on to say that the astrologer had told him that a terrible misfortune threatened him and his kingdom and the only way to prevent it was to shut Guna-Vara up in prison for the rest of her life. The poor queen could hardly believe that she had heard rightly. She knew she had done no wrong, and could not understand how putting her in prison could help anybody. She was quite sure that her husband loved her, and no words could have expressed her pain at the thought of being sent away from him and her dear son. Yet she made no resistance, not even asking Vira-Bhuja to let her see Sringa-Bhuja again. She just bowed her beautiful head and said: "Be it unto me as my Lord wills. If he wishes my death, I am ready to lay down my life."

This submission made the king feel even more unhappy than before. He longed to take his wife in his arms and tell her he would never let her go; and perhaps if she had looked at him then, he would have seen all her love for him in her eyes, but she remained perfectly still with bowed head, waiting to hear what her fate was to be. Then the thought entered Vira-Bhuja's mind: "She is afraid to look at me: what Ayasolekha said was true."

So the king summoned his guards and ordered them to take his wife to a strong prison and leave her there. She went with them without making any resistance, only turning once to look lovingly at her husband as she was led away. Vira-Bhuja returned to his own palace and had not been there very long when he got a message from Ayasolekha, begging him to give her an interview, for she had something of very great importance to tell him. The king consented at once, thinking to himself, "perhaps she has found out that what she told me about my dear Guna-Vara is not true."

Great then was his disappointment when the wicked woman told him she had discovered a plot against his life. The son of Guna-Vara and some of the chief men of the kingdom, she said, had agreed together to kill him, so that Sringa-Bhuja might reign in his stead. She and some of the other wives had overheard conversations between them, and were terrified lest their beloved Lord should be hurt. The young prince, she declared, had had some trouble in persuading the nobles to help him, but he had succeeded at last.

Vira-Bhuja simply could not believe this story, for he trusted his son as much as he loved him; and he sent the mischief maker away, telling her not to dare to enter his presence again. For all that he could not get the matter out of his head. He had Sringa-Bhuja carefully watched; and as nothing against him was found out, he was beginning to feel more easy in his mind, and even to think of going to see Guna-Vara in her prison to ask her to confide in him, when something happened which led him to fear that after all his dear son was not true to him. This was what made him uneasy. He had a wonderful arrow, set with precious jewels, which had been given to him by a magician, and had the power of hitting without fail whatever it was aimed at from however great a distance.

The very day he had meant to visit his ill-treated wife, he missed this arrow from the place in which he kept it concealed. This distressed him very much; and after seeking it in vain, he summoned all those who were employed in the palace to his presence, and asked if any of them knew anything about the arrow. He promised that he would forgive any one who helped him to get it back, even if it were the thief himself; but added that, if it was not found in three days, he would have all the servants beaten until the one who had stolen it confessed.

Now the fact of the matter was that Ayasolekha, who had told the wicked story about Guna-Vara, knew where the king kept the arrow, had taken it to her private rooms, and had sent for her own sons and those of the other wives, all of whom hated Sringa-Bhuja, to tell them of a plot to get their brother into disgrace, "You know," she said to them, "how much better your father loves Sringa-Bhuja than he does any of you; and that, when be dies, he will leave the kingdom and all his money to him. Now I will help you to prevent this by getting rid of Sringa-Bhuja.

"You must have a great shooting match, in which your brother will be delighted to take part, for he is very proud of his skill with the bow and arrow. On the day of the match, I will send for him and give him the jewelled arrow belonging to your father to shoot with, telling him the king had said I might lend it to him. Your father will then think he stole it and order him to be killed."

The brothers were all delighted at what they thought a very clever scheme, and did just what Ayasolekha advised. When the day came, great crowds assembled to see the shooting at a large target set up near the palace. The king himself and all his court were watching the scene from the walls, and it was difficult for the guards to keep the course clear.

The brothers, beginning at the eldest, all pretended to try and hit the target; but none of them really wished to succeed, because they thought that, when Sringa-Bhuja's turn came, as their father's youngest son, he would win the match with the jewelled arrow. Then the king would order him to be brought before him, and he would be condemned to death or imprisonment for life.

Now, as very often happens, something no one in the least expected upset the carefully planned plot. Just as Sringa-Bhuja was about to shoot at the target, a big crane flew on to the ground between him and it, so that it was impossible for him to take proper aim. The brothers, seeing the bird and anxious to shoot it for themselves, all began to clamour that they should be allowed to shoot again. Nobody made any objection, and Sringa-Bhuja stood aside, with the jewelled arrow in the bow, waiting to see what they would do, but feeling sure that he would be the one to kill the bird. Brother after brother tried, but the great creature still remained untouched, when a travelling mendicant stepped forward and cried aloud:

"That is no bird, but an evil magician who has taken that form to deceive you all. If he is not killed before he takes his own form again, he will bring misery and ruin upon this town and the surrounding country."

You know perhaps that mendicants or beggars in India are often holy men whose advice even kings are glad to listen to; so that, when everyone heard what this beggar said, there was great excitement and terror. For many were the stories told of the misfortunes Rakshas or evil magicians had brought on other cities. The brothers all wanted to try their luck once more, but the beggar checked them, saying:

"No, no. Where is your youngest brother Sringa-Bhuja? He alone will be able to save your homes, your wives and your children, from destruction,"

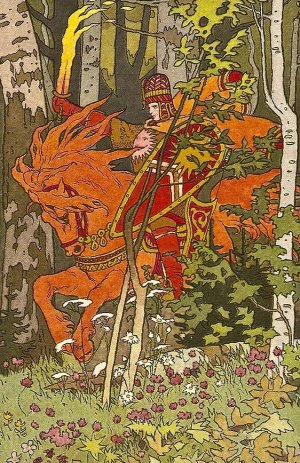

Then Sringa-Bhuja came forward; and as the sun flashed upon the jewels in the stolen arrow, revealing to the watching king that it was his own beloved son who had taken it, the young prince let it fly straight for the bird. It wounded but did not kill the crane, which flew off with the arrow sticking in its breast, the blood dripping from it in its flight, which became gradually slower and slower. At the sight of the bird going off with the precious jewelled arrow, the king was filled with rage, and sent orders that Sringa-Bhuja should be fetched to his presence immediately. But before the messengers reached him, he had started in pursuit of the bird, guided by the blood-drops on the ground.

As Sringa-Bhuja sped along after the crane, the beggar made some strange signs in the air with the staff he used to help him along; and such clouds of dust arose that no one could see in which direction the young prince had gone. The brothers and Ayasolekha were very much dismayed at the way things had turned out, and greatly feared that the king's anger would vent itself on them, now that Sringa-Bhuja had disappeared. Vira-Bhuja did send for them, and asked them many questions; but they all kept the secret of how Sringa-Bhuja had got the arrow, and promised to do all they could to help to get it back.

Again the king thought he would go and see the mother of his dear youngest son; but again something held him back, and poor Guna-Vara was left alone, no one ever going near her except the gaoler who took her her daily food. After trying everything possible to find out where Sringa-Bhuja had gone, the king began to show special favour to another of his sons; and as the months passed by, it seemed as if the young prince and the jewelled arrow were both forgotten.

Meanwhile Sringa-Bhuja travelled on and on in the track of the drops of blood, till he came to the outskirts of a fine forest, through which many beaten paths led to a very great city. He sat down to rest at the foot of a wide-spreading tree, and was gazing up at the towers and pinnacles of the town, rising far upwards towards the sky, when he had a feeling that he was no longer alone. He was right: for, coming slowly along one of the paths, was a lovely young girl, singing softly to herself in a beautiful voice. Her eyes were like those of a young doe, and her features were perfect in their form and expression, reminding Sringa-Bhuja of his mother, whom he was beginning to fear he would never see again.

When the young girl was quite close to him, he startled her by saying, "Can you tell me what is the name of this city?"

"Of course, I can," she replied, "for I live in it. It is called Dhuma-Pura, and it belongs to my father: he is a great magician named Agni-Sikha, who loves not strangers. Now tell me who you are and whence you come?"

Then Sringa-Bhuja told the maiden all about himself, and why he was wandering so far from home. The girl, whose name was Rupa-Sikha, listened very attentively; and when he came to the shooting of the crane, and how he had followed the bleeding bird in the hope of getting back his father's jewelled arrow, she began to tremble.

"Alas, alas!" she said. "The bird you shot was my father, who can take any form he chooses. He returned home but yesterday, and I drew the arrow from his wound and dressed the hurt myself. He gave me the jewelled arrow to keep, and I will never part with it. As for you, the sooner you depart the better; for my father never forgives, and he is so powerful that you would have no chance of escape if he knew you were here."

Hearing this, Sringa-Bhuja became very sad, not because he was afraid of Agni-Sikha, but because he knew that he already loved the fair maiden who stood beside him, and was resolved to make her his wife. She too felt drawn towards him and did not like to think of his going away.

Besides this, she had much to fear from her father, who was as cruel as he was mighty, and had caused the death already of many lovers who had wished to marry her. She had never cared for any of them, and had been content to live without a husband, spending her life in wandering about near her home and winning the love of all who lived near her, even that of the wild creatures of the forest, who would none of them dream of hurting her. Often and often she stood between the wrath of her father and those he wished to injure; for, wicked as he was, he loved her and wanted her to be happy,

Rupa-Sikha did not take long to decide what was best for her to do. She said to the prince, "I will give you back your golden arrow, and you must make all possible haste out of our country before my father discovers you are here."

"No! no! no! a thousand times no!" cried the prince. "Now I have once seen you, I can never, never leave you. Can you not learn to love me and be my wife?" Then he fell prostrate at her feet, and looked up into her face so lovingly that she could not resist him. She bent down towards him, and the next moment they were clasped in each other's arms, quite forgetting all the dangers that threatened them. Rupa-Sikha was the first to remember her father, and drawing herself away from her lover, she said to him:

"Listen to me, and I will tell you what we must do. My father is a magician, it is true, but I am his daughter, and I inherit some of his powers. If only you will promise to do exactly as I tell you, I think I may be able to save you, and perhaps even become your wife. I am the youngest of a large family and my father's favourite. I will go and tell him that a great and mighty prince, hearing of his wonderful gifts, has come to our land to ask for an interview with him. Then I will tell him that I have seen you, fallen in love with you, and want to marry you. He will be flattered to think his fame has spread so far, and will want to see you, even if he refuses to let me be your wife. I will lead you to his presence and leave you with him alone. If you really love me, you will find the way to win his consent; but you must keep out of his sight till I have prepared the way for you. Come with me now, and I will show you a hiding-place."

Rupa-Sikha then led the prince far away into the depths of the forest, and showed him a large tree, the wide-spreading branches of which touched the ground, completely hiding the trunk, in which there was an opening large enough for a man to pass through. Steps cut in the inside of the trunk led down to a wide space underground; and there the magician's daughter told her lover to wait for her return. "Before I go," she said, "I will tell you my own password, which will save you from death if you should be discovered. It is LOTUS FLOWER; and everyone to whom you say it, will know that you are under my protection."

When Rupa-Sikha reached the palace she found her father in a very bad humour, because she had not been to ask how the wound in his breast was getting on. She did her best to make up for her neglect; and when she had dressed the wound very carefully, she prepared a dainty meal for her father with her own hands, waiting upon him herself whilst he ate it. All this pleased him, and he was in quite an amiable mood when she said to him:

"Now I must tell you that I too have had an adventure. As I was gathering herbs in the forest, I met a man I had never seen before, a tall handsome young fellow looking like a prince, who told me he was seeking the palace of a great and wonderful magician, of whose marvellous deeds he had heard. Who could that magician have been but you, my father?" She added, "I told him I was your daughter, and he entreated me to ask you to grant him an interview."

Agni-Sikha listened to all this without answering a word. He was pleased at this fresh proof that his fame had spread far and wide; but he guessed at once that Rupa-Sikha had not told him the whole truth. He waited for her to go on, and as she said no more, he suddenly turned angrily upon her and in a loud voice asked her:

"And what did my daughter answer?"

Then Rupa-Sikha knew that her secret had been discovered. And rising to her full height, she answered proudly, "I told him I would seek you and ask you to receive him. And now I will tell you, my father, that I have seen the only man I will ever marry; and if you forbid me to do so, I will take my own life, for I cannot live without him."

"Send for the man immediately," cried the magician, "and you shall hear my answer when he appears before me."

"I cannot send," replied Rupa-Sikha, "for none knows where I have left him; nor will I fetch him till you promise that no evil shall befall him."

At first Agni-Sikha laughed aloud and declared that he would do no such thing. But his daughter was as obstinate as he was; and finding that he could not get his own way unless he yielded to her, he said crossly:

"He shall keep his fine head on his shoulders, and leave the palace alive; but that is all I will say."

"But that is not enough," said Rupa-Sikha. "Say after me, Not a hair of his head shall be harmed, and I will treat him as an honoured guest, or your eyes will never rest on him."

At last the magician promised, thinking to himself that he would find some way of disposing of Sringa-Bhuja, if he did not fancy him for a son-in-law. The words she wanted to hear were hardly out of her father's mouth before Rupa-Sikha sped away, as if on the wings of the wind, full of hope that all would be well. She found her lover anxiously awaiting her, and quickly explained how matters stood. "You had better say nothing about me to my father at first," she said; "but only talk about him and all you have heard of him. If only you could get him to like you and want to keep you with him, it would help us very much. Then you could pretend that you must go back to your own land; and rather than allow you to do so, he will be anxious for us to be married and to live here with him."

Sringa-Bhuja loved Rupa-Sikha so much that he was ready to obey her in whatever she asked. So he at once went with her to the palace. On every side he saw signs of the strength and power of the magician. Each gate was guarded by tall soldiers in shining armour, who saluted Rupa-Sikha but scowled fiercely at him. He knew full well that, if he had tried to pass alone, they would have prevented him from doing so. At last the two came to the great hall, where the magician was walking backwards and forwards, working himself into a rage at being kept waiting.

Directly he looked at the prince, he knew him for the man who had shot the jewelled arrow at him when he had taken the form of a crane, and he determined that he would be revenged. He was too cunning to let Sringa-Bhuja guess that he knew him, and pretended to be very glad to see him.

He even went so far as to say that he had long wished to find a prince worthy to wed his youngest and favourite daughter. "You," he added, "seem to me the very man, young, handsome and--to judge from the richness of your dress and jewels--able to give my beloved one all she needs."

The prince could hardly believe his ears, and Rupa-Sikha also was very much surprised. She guessed however that her father had some evil purpose in what he said, and looked earnestly at Sringa-Bhuja in the hope of making him understand. But the prince was so overjoyed at the thought that she was to be his wife that he noticed nothing. So when Agni-Sikha added, "I only make one condition: you must promise that you will never disobey my commands, but do whatever I tell you without a moment's hesitation," Sringa-Bhuja, without waiting to think, said at once, "Only give me your daughter and I will serve you in any way you wish."

"That's settled then!" cried the magician, and he clapped his hands together. In a moment a number of attendants appeared, and their master ordered them to lead the prince to the best apartments in the palace, to prepare a bath for him, and do everything he asked them.

As Sringa-Bhuja followed the servants, Rupa-Sikha managed to whisper to him, "Beware! await a message from me!" When he had bathed and was arraying himself in fresh garments provided by his host, waited on, hand and foot, by servants who treated him with the greatest respect, a messenger arrived, bearing a sealed letter which he reverently handed to the prince. Sringa-Bhuja guessed at once from whom it came; and anxious to read it alone, he hastily finished his toilette and dismissed the attendants.

"My beloved," said the letter - which was, of course, from Rupa-Sikha - "My father is plotting against you; and very foolish were you to promise you would obey him in all things. I have ten sisters all exactly like me, all wearing dresses and necklaces which are exact copies of each other, so that few can tell me from the others, Soon you will be sent for to the great Hall and we shall all be together there. My father will bid you choose your bride from amongst us; and if you make a mistake all will be over for us. But I will wear my necklace on my head instead of round my neck, and thus will you know your own true love. And remember, my dearest, to obey no future command without hearing from me, for I alone am able to outwit my terrible father,"

Everything happened exactly as Rupa-Sikha described. The prince was sent for by Agni-Sikha, who, as soon as he appeared, gave him a garland of flowers and told him to place it round the neck of the maiden who was his promised bride. Without a moment's hesitation Sringa-Bhuja picked out the right sister; and the magician, though inwardly enraged, pretended to be so delighted at this proof of a lover's clear-sightedness that he cried:

"You are the son-in-law for me! The wedding shall take place to-morrow!"

When Sringa-Bhuja heard what Agni-Sikha said, he was full of joy; but Rupa-Sikha knew well that her father did not mean a word of it. She waited quietly beside her lover, till the magician bade all the sisters but herself leave the hall. Then the magician, with a very wicked look on his face, said:

"Before the ceremony there is just one little thing you must do for me, dear son-in-law that is to be. Go outside the town, and near the most westerly tower you will find a team of oxen and a plough awaiting you. Close to them is a pile of three hundred bushels of sesame seed. This you must sow this very day, or instead of a bridegroom you will be a dead man to-morrow."

Great was the dismay of Sringa-Bhuja when he heard this. But Rupa-Sikha whispered to him, "Fear not, for I will help you." Sadly the prince left the palace alone, to seek the field outside the city; the guards, who knew he was the accepted lover of their favourite mistress, letting him pass unhindered. There, sure enough, near the western tower were the oxen, the plough and a great pile of seed.

Never before had poor Sringa-Bhuja had to work for himself, but his great love for Rupa-Sikha made him determine to do his best. So he was about to begin to guide the oxen across the field, when, behold, all was suddenly changed. Instead of an unploughed tract of land, covered with weeds, was a field with rows and rows of regular furrows. The piles of seed were gone, and flocks of birds were gathering in the hope of securing some of it as it lay in the furrows.

As Sringa-Bhuja was staring in amazement at this beautiful scene, he saw Rupa-Sikha, looking more lovely than ever, coming towards him. "Not in vain," she said to him, "am I my father's daughter. I too know how to compel even nature to do my will; but the danger is not over yet. Go quickly back to the palace, and tell Agni-Sikha that his wishes are fulfilled."

The magician was very angry indeed when he heard that the field was ploughed and the seed sown. He knew at once that some magic had been at work, and suspected that Rupa-Sikha was the cause of his disappointment. Without a moment's hesitation he said to the prince: "No sooner were you gone than I decided not to have that seed sown. Go back at once, and pile it up where it was before."

This time Sringa-Bhuja felt no fear or hesitation, for he was sure of the power and will to help him of his promised bride. So back he went to the field, and there he found the whole vast space covered with millions and millions of ants, busily collecting the seed and piling it up against the wall of the town. Again Rupa-Sikha came to cheer him, and again she warned him that their trials were not yet over. She feared, she said, that her father might prove stronger than herself; for he had many allies at neighbouring courts ready to help him in his evil purposes. "Whatever else he orders you to do, you must see me before you leave the palace. I will send my faithful messenger to appoint a meeting in some secret place."

Agni-Sikha was not much surprised when the prince told him that his last order had been obeyed, and thought to himself, "I must get this tiresome fellow out of my domain, where that too clever child of mine will not be able to help him." "Well," he said, "I suppose the wedding must take place to-morrow after all, for I am a man of my word. We must now set about inviting the guests. You shall have the pleasure of doing this yourself: then my friends will know beforehand what a handsome young son-in-law I shall have.

The first person to summon to the wedding is my brother Dhuma Sikha, who has taken up his abode in a deserted temple a few miles from here. You must ride at once to that temple, rein up your steed opposite it, and cry, 'Dhuma Sikha, your brother Agni-Sikha has sent me hither to invite you to witness my marriage with his daughter Rupa-Sikha to-morrow. Come without delay!' Your message given, ride back to me; and I will tell you what farther tasks you must perform before the happy morrow dawns."

When Sringa-Bhuja left the palace, he knew not where to seek a horse to bear him on this new errand. But as he was nearing the gateway by which he had gone forth to sow the field with seed, a handsome boy approached him and said, "If my lord will follow me, I will tell him what to do." Somehow the voice sounded familiar; and when the guards were left far enough behind to be out of hearing, the boy looked up at Sringa-Bhuja with a smile that revealed Rupa-Sikha herself. "Come with me," she said; and taking his hand, she led him to a tree beneath which stood a noble horse, richly caparisoned, which pawed the ground and whinnied to its mistress, as she drew near.

"You must ride this horse," said Rupa-Sikha, "who will obey you if you but whisper in his ear; and you must take earth, water, wood and fire with you, which I will give you. You must go straight to the temple, and when you have called out your message, turn without a moment's delay, and ride for your life as swiftly as your steed will go, looking behind you all the time. No guidance will be necessary; for Marut - that is my horse's name - knows well what he has to do."

Then Rupa-Sikha gave Sringa-Bhuja a bowl of earth, a jar of water, a bundle of thorns and a brazier full of burning charcoal, hanging them by strong thongs upon the front of his saddle so that he could reach them easily. "My father," she told him, "has given my uncle instructions to kill you, and he will follow you upon his swift Arab steed. When you hear him behind you, fling earth in his path; if that does not stop him, pour out some of the water; and if he still perseveres, scatter the burning charcoal before him."

Away went the prince after he had received these instructions; and very soon he found himself opposite the temple, with the images of three of the gods worshipped in India to prove that it had been a sanctuary before the magician took up his abode in it. Directly Sringa-Bhuja shouted out his message to Dhuma-Sikha, the wicked dweller in the temple came rushing forth from the gateway, mounted on a huge horse, which seemed to be belching forth flames from its nostrils as it bounded along.

For one terrible moment Sringa-Bhuja feared that he was lost; but Marut, putting forth all his strength, kept a little in advance of the enemy, giving the prince time to scatter earth behind him. Immediately a great mountain rose up, barring the road, and Sringa-Bhuja felt that he was saved. He was mistaken: for, as he looked back, he saw Dhuma-Sikha coming over the top of the mountain.

The next moment the magician was close upon him. So he emptied his bowl of water: and, behold, a huge river with great waves hid pursuer and pursued from each other. Even this did not stop the mighty Arab horse, which swam rapidly across, the rider loudly shouting out orders to the prince to stop.

When the prince heard the hoofs striking on the dry ground behind him again, he threw out the thorns, and a dense wood sprouted up as if by magic, which for a few moments gave fresh hope of safety to Sringa-Bhuja; for it seemed as if even the powerful magician would be unable to get through it. He did succeed however; but his clothes were nearly torn off his back, and his horse was bleeding from many wounds made by the cruel thorns. Sringa-Bhuja too was getting weary, and remembered that he had only one more chance of checking his relentless enemy. He could almost feel the breath of the panting steed as it drew near; and with a loud cry to his beloved Rupa-Sikha, he threw the burning charcoal on the road.

In an instant the grass by the wayside, the trees overshadowing it, and the magic wood which had sprung from the thorns, were alight, burning so fiercely that no living thing could approach them safely. The wicked magician was beaten at last, and was soon himself fleeing away, as fast as he could, with the flames following after him as if they were eager to consume him.

Whether his enemy ever got back to his temple, Sringa-Bhuja never knew. Exhausted with all he had been through, the young prince was taken back to the palace by the faithful Marut, and there he found his dear Rupa-Sikha awaiting him. She told him that her father had promised her that, if the prince came back, he would oppose her marriage no longer. "For," he said, "if he can escape your uncle, he must be more than mortal, and worthy even of my daughter." "He does not in the least expect to see you again," added Rupa-Sikha; "and even if he allows us to marry, he will never cease to hate you; for I am quite sure he knows that you shot the jewelled arrow at him when he was in the form of a crane. If I ever am your wife, he will try to punish you through me. But have no fear: I shall know how to manage him. Fresh powers have been lately given to me by another uncle whose magic is stronger than that of any of my other relations."

When Sringa-Bhuja had bathed and rested, he robed himself once more in the garments he had worn the day he first saw Rupa-Sikha; and together the lovers went to the great hall to seek an interview with Agni-Sikha. The magician, who had made quite sure that he had now got rid of the unwelcome suitor for his daughter's hand, could not contain his rage, at seeing him walk in with her as if the two were already wedded.

He stamped about, pouring out abuse, until he had quite exhausted himself, the lovers looking on quietly without speaking. At last, coming close to them, Agni-Sikha shouted, in a loud harsh voice: "So you have not obeyed my orders. You have not bid my brother to the wedding. Your life is forfeit, and you will die to-morrow instead of marrying Rupa-Sikha. Describe the temple in which Dhuma Sikha lives and the appearance of its owner."

Then Sringa-Bhuja gave such an exact account of the temple, naming the gods whose images still adorned it, and of the terrible man riding the noble steed who had pursued him, that the magician was convinced against his will; and knowing that he must keep his word to Rupa-Sikha, he gave his consent for the preparations for the marriage on the morrow to begin.

The marriage was celebrated the next day with very great pomp; and a beautiful suite of rooms was given to the bride and bridegroom, who could not in spite of this feel safe or happy, because they knew full well that Agni-Sikha hated them. The prince soon began to feel home-sick and anxious to introduce his beautiful wife to his own people. He remembered that he had left his dear mother in prison, and reproached himself for having forgotten her for so long. So he said to Rupa-Sikha:

"Let us go, beloved, to my native city, Vardhamana. My heart yearns after my dear ones there, and I would fain introduce you to them."

"My lord," replied Rupa-Sikha, "I will go with you whither you will, were it even to the ends of the earth. But we must not let my father guess we mean to go; for he would forbid us to leave the country and set spies to watch our every movement. We will steal away secretly, riding together on my faithful Marut and taking with us only what we can carry." "And my jewelled arrow," said the prince, "that I may give it back to my father and explain to him how I lost it. Then shall I be restored to his favour, and maybe he will forgive my mother also."

"Have no fear," answered Rupa-Sikha: "all will surely go well with us. Forget not that new powers have been given to me, which will save us from my father and aid me to rescue my dear one's mother from her evil fate."

Before the dawn broke on the next day, the two set forth unattended, Marut seeming to take pride in his double burden and bearing them along so swiftly that they had all but reached the bounds of the country under the dominion of Agni-Sikha as the sun rose. Just as they thought they were safe from pursuit, they heard a loud rushing noise behind; and looking round, they saw the father of the bride close upon them on his Arab steed, with sword uplifted in his hand to strike. "Fear not," whispered Rupa-Sikha to her husband. "I will show you now what I can do." And waving her arms to and fro, as she muttered some strange words, she changed herself into an old woman and Sringa-Bhuja into an old man, whilst Marut became a great pile of wood by the road-side.

When the angry father reached the spot, the bride and bridegroom were busily gathering sticks to add to the pile, seemingly too absorbed in their work to take any notice of the angry magician, who shouted out to them:

"Have you seen a man and a woman pass along this way?"

The old woman straightened herself, and peering, up into his face, said:

"No; we are too busy over our work to notice anything else."

"And what, pray, are you doing in my wood?" asked Agni-Sikha.

"We are helping to collect the fuel for the pyre of the great magician Agni-Sikha." answered Rupa-Sikha. "Do you not know that he died yesterday?"

The Hindus of India do not bury but burn the dead; so that it was quite a natural thing for the people of the land over which the magician ruled to collect the materials for the pyre or heap of wood on which his body would be laid to be burnt. What surprised Agni-Sikha, and in fact nearly took his breath away, was to be quietly told that he was dead. He began to think that he was dreaming, and said to himself, "I cannot really be dead without knowing it, so I must be asleep." And he quietly turned his horse round and rode slowly home again. This was just what his daughter wanted; and as soon as he was out of sight, she turned herself, her husband and Marut, into their natural forms again, laughing merrily, as she did so, at the thought of the ease with which she had got rid of her father.

Once more the bride and bridegroom set forth on their way, and once more they soon heard Agni-Sikha coming after them. For when he got back to his palace, and the servants hastened out to take his horse, he guessed that a trick had been played on him. He did not even dismount, but just turned his horse's head round and galloped back again. "If ever," he thought to himself, "I catch those two young people, I'll make them wish they had obeyed me. Yes, they shall suffer for it. I am not going to stand being defied like this."

This time Rupa-Sikha contented herself with making her husband and Marut invisible, whilst she changed herself into a letter-carrier, hurrying along the road as if not a moment was to be lost. She took no notice of her father, till he reined up his steed and shouted to her:

"Have you seen a man and woman on horseback pass by?"

"No, indeed," she said: "I have a very important letter to deliver, and could think of nothing but making all the haste possible."

"And what is this important letter about?" asked Agni-Sikha. "Can you tell me that?"

"Oh, yes, I can tell you that," she said. "But where can you have been, not to have heard the terrible news about the ruler of this land?"

"You can't tell me anything I don't know about him," answered the magician, "for he is my greatest friend."

"Then you know that he is dying from a wound he got in a battle with his enemies only yesterday. I am to take this letter to his brother Dhuma-Sikha, bidding him come to see him before the end."

Again Agni-Sikha wondered if he were dreaming, or if he were under some strange spell and did not really know who he was? Being able, as he was, to cast spells on other people, he was ready to fancy the same thing had befallen him. He said nothing when he heard that he was wounded, and was about to turn back again when Rupa-Sikha said to him:

"As you are on horseback and can get to Dhuma-Sikha's temple quicker than I can, will you carry the message of his brother's approaching death to him for me, and bid him make all possible haste if he would see him alive?"

This was altogether too much for the magician, who became sure that there was something very wrong about him. He knew he was not wounded or dying, but he thought he must be ill of fever, fancying he heard what he did not. He stared fixedly at his daughter, and she stared up at him, half-afraid he might find out who she was, but he never guessed.

"Do your own errands," he said at last; and slashing his poor innocent horse with his whip, he wheeled round and dashed home again as fast as he could. Again his servants ran out to receive him, and he gloomily dismounted, telling them to send his chief councillor to him in his private apartments. Shut up with him, he poured out all his troubles, and the councillor advised him to see his physician without any delay, for he felt sure that these strange fancies were caused by illness.

The doctor, when he came, was very much puzzled, but he looked as wise as he could, ordered perfect rest and all manner of disagreeable medicines. He was very much surprised at the change he noticed in his patient, who, instead of angrily declaring that there was nothing the matter with him, was evidently in a great fright about his health. He shut himself up for many days, and it was a long time before he got over the shock he had received, and then it was too late for him to be revenged or the lovers.

Having really got rid of Agni-Sikha, Rupa-Sikha and her husband were very soon out of his reach and in the country belonging to Sringa-Bhuja's father, who had bitterly mourned the loss of his favourite son. When the news was brought to him that two strangers, a handsome young man and a beautiful woman, who appeared to be husband and wife, had entered his capital, he hastened forth to meet them, hoping that perhaps they could give him news of Sringa-Bhuja.

What was his joy when he recognised his dear son, holding the jewelled arrow, which had led him into such trouble, in his right hand, as he guided Marat with his left! The king flung himself from his horse, and Sringa-Bhuja, giving the reins to Rupa-Sikha, also dismounted. The next moment he was in his father's arms, everything forgotten and forgiven in the happy reunion.

Great was the rejoicing over Sringa-Bhuja's return and hearty was the welcome given to his beautiful bride, who quickly won all hearts but those of the wicked wives and sons who had tried to harm her husband and his mother. They feared the anger of the king, when he found out how they had deceived him, and they were right to fear. Sringa-Bhuja's very first act was to plead for his mother to be set free. He would not tell any of his adventures, he said, till she could hear them too; and the king, full of remorse for the way he had treated her, went with him to the prison in which she had been shut up all this time.

What was poor Guna-Vara's joy, when the two entered the place in which she had shed so many tears! She could not at first believe her eyes or ears, but soon she realised that her sufferings were indeed over. She could not be quite happy till her beloved husband said he knew she had never loved any one but him. She had been accused falsely, she said, and she wanted the woman who had told a lie about her to be made to own the truth.

This was done in the presence of the whole court, and when judgment had been passed upon Ayasolekha, the brothers of Sringa-Bhuja were also brought before their father, who charged them with having deceived him. They too were condemned, and all the culprits would have been taken to prison and shut up for the rest of their lives, if those they had injured had not pleaded for their forgiveness. Guna-Vara and her son prostrated themselves at the foot of the throne, and would not rise till they had won pardon for their enemies.

Ayasolekha and the brothers were allowed to go free; but Sringa-Bhuja, though he was the youngest of all the princes, was proclaimed heir to the crown after his father's death. His brothers, however, never ceased to hate him; and when he came to the throne, they gave him a great deal of trouble.

He had many years of happiness with his wife and parents before that, and never regretted the mistake about the jewelled arrow; since but for it he would, he knew, never have seen his beloved Rupa-Sikha.

Source: Hindu Tales from the Sanskrit; translated by S. M. Mitra, adapted by Arthur Bell