| News / Space News |

Hubble Finds Saturn's Rings Heating Its Atmosphere

The secret has been hiding in plain view for 40 years. But it took the insight of a veteran astronomer to pull it all together within a year, using observations of Saturn from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and retired Cassini probe, in addition to the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft and the retired International Ultraviolet Explorer mission.

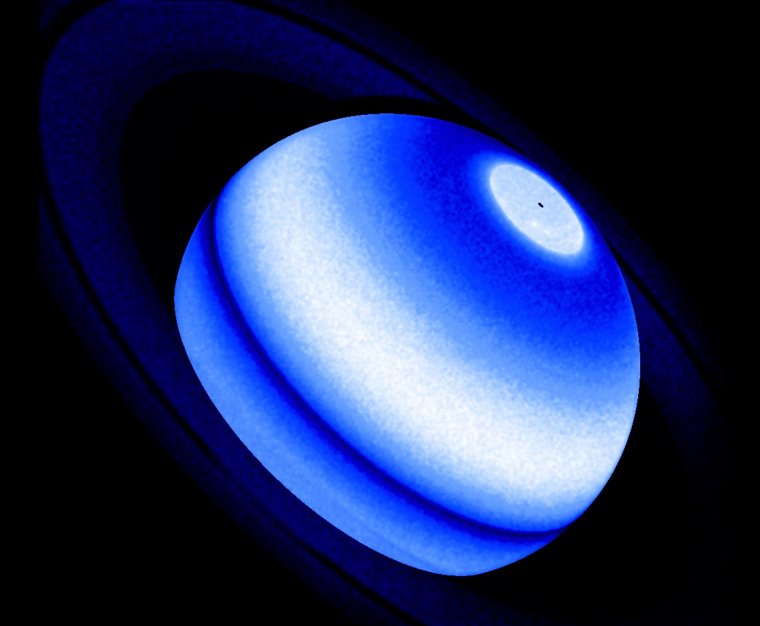

This composite image shows the Saturn Lyman-alpha bulge, an emission from hydrogen which is a persistent and unexpected excess detected by three distinct NASA missions, namely Voyager 1, Cassini, and the Hubble Space Telescope between 1980 and 2017. A Hubble near-ultraviolet image, obtained in 2017 during the Saturn summer in the northern hemisphere, is used as a reference to sketch the Lyman-alpha emission of the planet. The rings appear much darker than the planet's body because they reflect much less ultraviolet sunlight. Photo: NASA, ESA, Lotfi Ben-Jaffel (IAP & LPL)

Saturn's vast ring system is heating the giant planet's upper atmosphere. The phenomenon has never before been seen in the solar system. It's an unexpected interaction between Saturn and its rings that potentially could provide a tool for predicting if planets around other stars have glorious Saturn-like ring systems, too.

The telltale evidence is an excess of ultraviolet radiation, seen as a spectral line of hot hydrogen in Saturn's atmosphere. The bump in radiation means that something is contaminating and heating the upper atmosphere from the outside.

The most feasible explanation is that icy ring particles raining down onto Saturn's atmosphere cause this heating. This could be due to the impact of micrometeorites, solar wind particle bombardment, solar ultraviolet radiation, or electromagnetic forces picking up electrically charged dust.

All this happens under the influence of Saturn's gravitational field pulling particles into the planet. When NASA's Cassini probe plunged into Saturn's atmosphere at the end of its mission in 2017, it measured the atmospheric constituents and confirmed that many particles are falling in from the rings.

"Though the slow disintegration of the rings is well known, its influence on the atomic hydrogen of the planet is a surprise. From the Cassini probe, we already knew about the rings' influence. However, we knew nothing about the atomic hydrogen content," said Lotfi Ben-Jaffel of the Institute of Astrophysics in Paris and the Lunar & Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona.

"Everything is driven by ring particles cascading into the atmosphere at specific latitudes. They modify the upper atmosphere, changing the composition," said Ben-Jaffel. "And then you also have collisional processes with atmospheric gasses that are probably heating the atmosphere at a specific altitude."

Ben-Jaffel's conclusion required pulling together archival ultraviolet-light (UV) observations from four space missions that studied Saturn. This includes observations from the two NASA Voyager probes that flew by Saturn in the 1980s and measured the UV excess. At the time, astronomers dismissed the measurements as noise in the detectors.

The Cassini mission, which arrived at Saturn in 2004, also collected UV data on the atmosphere (over several years). Additional data came from Hubble and the International Ultraviolet Explorer, which launched in 1978.

But the lingering question was whether all the data could be illusory, or instead reflected a true phenomenon on Saturn.

The key to assembling the jigsaw puzzle came in Ben-Jaffel's decision to use measurements from Hubble's Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS).

Its precision observations of Saturn were used to calibrate the archival UV data from all four other space missions that have observed Saturn. He compared the STIS UV observations of Saturn to the distribution of light from multiple space missions and instruments.

"When everything was calibrated, we saw clearly that the spectra are consistent across all the missions. This was possible because we have the same reference point, from Hubble, on the rate of transfer of energy from the atmosphere as measured over decades," Ben-Jaffel said. "It was really a surprise for me. I just plotted the different light distribution data together, and then I realized, wow – it's the same."

Four decades of UV data cover multiple solar cycles and help astronomers study the Sun's seasonal effects on Saturn. By bringing all the diverse data together and calibrating it, Ben-Jaffel found that there is no difference to the level of UV radiation.

"At any time, at any position on the planet, we can follow the UV level of radiation," he said. This points to the steady "ice rain" from Saturn's rings as the best explanation. (NASA)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE