| News / Space News |

Hubble Finds That Betelgeuse's Mysterious Dimming Is Due to a Traumatic Outburst

Observations by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope are showing that the unexpected dimming of the supergiant star Betelgeuse was most likely caused by an immense amount of hot material ejected into space, forming a dust cloud that blocked starlight coming from Betelgeuse's surface.

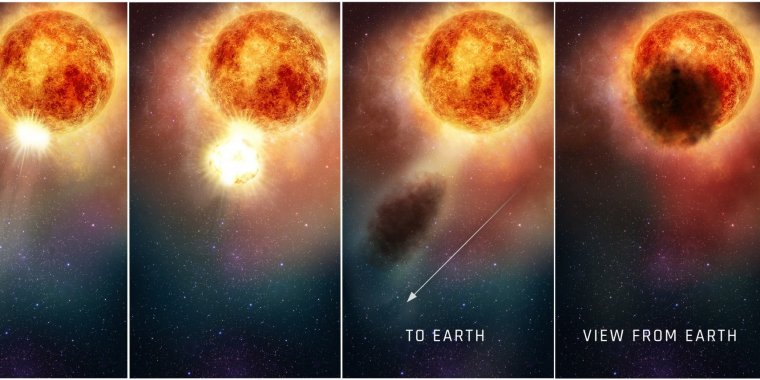

This four-panel graphic illustrates how the southern region of the rapidly evolving, bright, red supergiant star Betelgeuse may have suddenly become fainter for several months during late 2019 and early 2020. In the first two panels, as seen in ultraviolet light with the Hubble Space Telescope, a bright, hot blob of plasma is ejected from the emergence of a huge convection cell on the star's surface. In panel three, the outflowing, expelled gas rapidly expands outward. It cools to form an enormous cloud of obscuring dust grains. The final panel reveals the huge dust cloud blocking the light (as seen from Earth) from a quarter of the star's surface.

Photo: NASA, ESA, E. Wheatley (STScI)

Hubble researchers suggest that the dust cloud formed when superhot plasma unleashed from an upwelling of a large convection cell on the star's surface passed through the hot atmosphere to the colder outer layers, where it cooled and formed dust grains.

The resulting dust cloud blocked light from about a quarter of the star's surface, beginning in late 2019. By April 2020, the star returned to normal brightness.

Betelgeuse is an aging, red supergiant star that has swelled in size due to complex, evolving changes in its nuclear fusion furnace at the core. The star is so huge now that if it replaced the Sun at the center of our solar system, its outer surface would extend past the orbit of Jupiter.

The unprecedented phenomenon for Betelgeuse's great dimming, eventually noticeable to even the naked eye, started in October 2019. By mid-February 2020, the monster star had lost more than two-thirds of its brilliance.

Hubble captured signs of dense, heated material moving through the star's atmosphere in September, October, and November 2019. Then, in December, several ground-based telescopes observed the star decreasing in brightness in its southern hemisphere.

“With Hubble, we see the material as it left the star’s visible surface and moved out through the atmosphere, before the dust formed that caused the star to appear to dim,” said Andrea Dupree, associate director of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA), Cambridge, Massachusetts. “We could see the effect of a dense, hot region in the southeast part of the star moving outward.

"This material was two to four times more luminous than the star's normal brightness," she continued. "And then, about a month later, the south part of Betelgeuse dimmed conspicuously as the star grew fainter. We think it is possible that a dark cloud resulted from the outflow that Hubble detected. Only Hubble gives us this evidence that led up to the dimming."

Hubble's ultraviolet-light sensitivity allowed researchers to probe the layers above the star's surface, which are so hot — more than 20,000 degrees Fahrenheit — they cannot be detected at visible wavelengths. These layers are heated partly by the star's turbulent convection cells bubbling up to the surface.

This hot, dense material continued to travel beyond Betelgeuse's visible surface, reaching millions of miles from the seething star. At that distance, the material cooled down enough to form dust, the researchers said.

This interpretation is consistent with Hubble ultraviolet-light observations in February 2020, which showed that the behavior of the star's outer atmosphere returned to normal, even though visible-light images showed that it was still dimming.

Although Dupree does not know the outburst's cause, she thinks it was aided by the star's pulsation cycle, which continued normally though the event, as recorded by visible-light observations. The star was expanding in its cycle at the same time as the upwelling of the convective cell.

The pulsation rippling outward from Betelgeuse may have helped propel the outflowing plasma through the atmosphere.

Dupree estimates that about two times the normal amount of material from the southern hemisphere was lost over the three months of the outburst. Betelgeuse, like all stars, is losing mass all the time, in this case at a rate 30 million times higher than the Sun.

Betelgeuse is so close to Earth, and so large, that Hubble has been able to resolve surface features – making it the only such star, except for our Sun, where surface detail can be seen.

The red supergiant is destined to end its life in a supernova blast. Some astronomers think the sudden dimming may be a pre-supernova event.

The star is relatively nearby, about 725 light-years away, which means the dimming would have happened around the year 1300. But its light is just reaching Earth now. (NASA)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE