| News / Space News |

'Iceball' Planet Discovered Through Microlensing

Scientists have discovered a new planet with the mass of Earth, orbiting its star at the same distance that we orbit our sun. The planet is likely far too cold to be habitable for life as we know it, however, because its star is so faint.

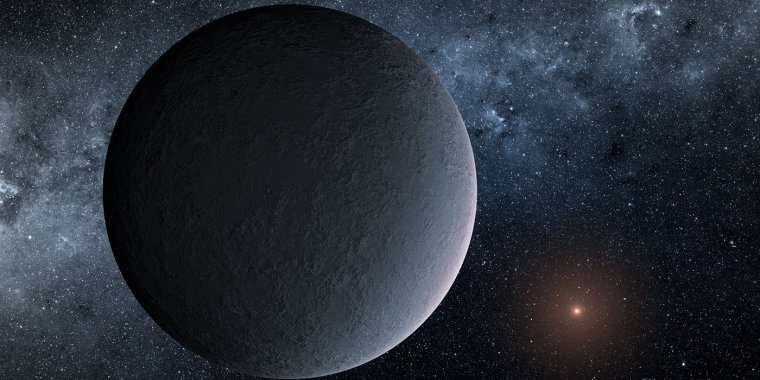

This artist's concept shows OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb, a planet discovered through a technique called microlensing. ![]()

This 'iceball' planet is the lowest-mass planet ever found through microlensing.

Microlensing is a technique that facilitates the discovery of distant objects by using background stars as flashlights.

When a star crosses precisely in front of a bright star in the background, the gravity of the foreground star focuses the light of the background star, making it appear brighter. A planet orbiting the foreground object may cause an additional blip in the star's brightness. In this case, the blip only lasted a few hours.

This technique has found the most distant known exoplanets from Earth, and can detect low-mass planets that are substantially farther from their stars than Earth is from our sun.

The newly discovered planet, called OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb, aids scientists in their quest to figure out the distribution of planets in our galaxy.

An open question is whether there is a difference in the frequency of planets in the Milky Way's central bulge compared to its disk, the pancake-like region surrounding the bulge. OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb is located in the disk, as are two planets previously detected through microlensing by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope.

Although OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb is about the same mass as Earth, and the same distance from its host star as our planet is from our sun, the similarities may end there.

OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb is nearly 13,000 light-years away and orbits a star so small, scientists aren't sure if it's a star at all. It could be a brown dwarf, a star-like object whose core is not hot enough to generate energy through nuclear fusion. This particular star is only 7.8 percent the mass of our sun, right on the border between being a star and not.

Alternatively, it could be an ultra-cool dwarf star much like TRAPPIST-1, which Spitzer and ground-based telescopes recently revealed to host seven Earth-size planets.

Those seven planets all huddle closely around TRAPPIST-1, even closer than Mercury orbits our sun, and they all have potential for liquid water. But OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb, at the sun-Earth distance from a very faint star, would be extremely cold -- likely even colder than Pluto is in our own solar system, such that any surface water would be frozen.

A planet would need to orbit much closer to the tiny, faint star to receive enough light to maintain liquid water on its surface. (NASA)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE