| Titi Tudorancea TV / Documentaries |

Introduction to Advaita Vedanta

Part 5/6: Ishvara - Blind Faith vs Knowledge

A video presentation by Swami Tadatmananda Saraswati, Arsha Bodha Center, United States

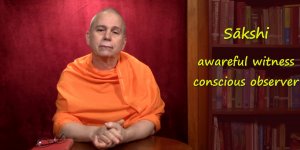

(Tapescript) Welcome! In this series of presentations so far, we’ve been engaged in a process of self-inquiry, atma vichara.

We’ve looked inside ourselves, within our bodies and minds, seeking to discover the extraordinary nature of atma, the true self, the unborn, unchanging consciousness that illumines our minds and is the source of contentment.

Having completed this initial, inward-turned inquiry, in this presentation, we’ll turn our attention outwards, towards the world around us, to understand the complex universe in which we live.

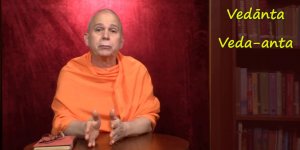

We’ll follow the traditional teaching methodology of Vedanta to understand, not only the world around us, but also the source or creator from which this world arose, as well as the nature of our relationship with both the world and with its creator.

That’s a lot to examine, so let’s get started.

You’ve probably looked up into the night sky, and found yourself entranced by the vast expanse of space, filled with planets, stars, and galaxies stretching out to inconceivably great distances.

Perhaps you’ve also wondered, “What is all this? Where did it come from? And how did I get here?”

These three questions form the basis for our present discussion.

These same three questions were pondered by the ancient rishis, who engaged in a process of exploration that culminated in the profound discoveries we’ll be considering shortly.

First of all, let’s take up the easiest of the three questions: “What is all this? What is the nature of the universe and what is it made of?”

From the standpoint of modern science, the universe is composed of matter and energy. Particles, like electrons and protons, combine to form 92 natural elements that are the building blocks for all that exists in the universe, including our own bodies.

Of course, in ancient times, none of this was known. What the rishis understood was based on a prescientific world view.

Instead of matter and energy, they considered the universe to be based on three qualities or gunas.

Those gunas are tamas, the quality of inertia; rajas, the quality of activity; and sattva, the quality of purity. These three gunas are considered the fundamental constituents from which everything in the universe arises.

For example, the physical elements, what we call matter, arise from the quality of tamas.

But, the ancients recognized only five elements - space, air, fire, water, and earth.

Obviously, there are huge differences between the modern and ancient world views, but they agree on one important point: this universe is made of fundamental stuff. Whether we define that stuff as three gunas or as matter and energy doesn’t really make any difference in this inquiry.

Now, we can turn to the second question, “Where did all this come from?”

Based on our discussion above, we could rephrase the question, “Where did the three gunas come from?” or, “Where did matter and energy come from?”

Science traces the origin of the universe to the big bang. About 14 billion years ago, an infinitely small, infinitely hot, infinitely dense object, known as a singularity, exploded with unimaginable force.

That explosion continues even today as our universe goes on expanding.

That’s all fine, but we can still ask, “Where did the singularity that exploded come from?”

With this question, we reach the limits of science, because scientists are unable to peer into the time before the big bang.

Why not?

Because time itself came into existence with the Big Bang. There was no such thing as time before the Big Bang, so how can we ask, "what chronologically preceded it?”

Yet, some scientists speculate that the singularity might somehow be a remnant of another universe that no longer exists. This idea is surprisingly similar to the teachings of Vedanta. Those teachings describe a cyclic universe, a universe that goes through cycles of manifestation and dissolution.

Just as living beings are subject to a cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, the universe, too, undergoes a similar cycle; this universe was preceded by a prior universe, which was itself preceded by yet another universe, and so on.

But then you might ask, “When did the first universe come into existence?”

But, that’s like asking, “Where does a circle begin? Where is its starting point?”

By definition, a cycle, like a circle, has no beginning and no end, it just keeps on going.

From this, we can conclude that an infinite number of universes have already come and gone, and the universe in which we live will be followed by that many more.

Ok, but we can still ask, “Where did this infinite series of universes come from?” Or, we could ask a related question, “Who or what is the source or creator of this cyclic universe?”

Up to this point, our inquiry has been focused on cosmology, the study of the cosmos.

But with questions such as these, our inquiry crosses a line, so to speak, from cosmology to theology, the study of theos, the Greek word for God.

Vedanta’s approach to theology, as we will soon see, is radically different from the approach adopted by the Western religions - Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

In these religions, God is an article of faith. The existence and nature of God is purely a matter of belief; it’s utterly beyond the scope of any kind of reasoning or rational deliberation. The Bible and the Koran are the scriptural bases for these beliefs. And scripture alone is considered authoritative and scripture stands on its own without needing any support from logic or reason.

Therefore, steadfast faith in the scriptures is essential. And that faith is blind faith, faith that’s not supported by logic or reason.

In fact, reason is often looked upon with skepticism or even with contempt, because reason can sometimes contradict what’s taught in the Bible and the Koran.

Unlike the Western religions, Vedanta never severs scriptural revelation from reason and rational discourse. Quite the opposite. Vedanta meticulously reconciles any logical discrepancies. If a scripture can’t be reconciled with both reason and experience, it won’t be accepted on face value.

The great Vedantic scholar, Shankaracharya, famously said in his Bhagavad Gita's commentary, “If a hundred scriptures say that fire is cold or dark, none of those scriptures can be accepted as authoritative.”

Now, to better understand the relationship between scripture and reason, we can reflect on a short passage from the Bhagavad Gita, a passage that says, shraddhavan labhate jnanam, one who has shraddha - faith, labhate - gains, jnanam - knowledge.

Based on this passage, faith itself is not the goal; it’s just the beginning point of a process of inquiry that eventually culminates in the acquisition of knowledge, in this case, knowledge of the existence and nature of God.

But, how can faith lead to knowledge? Let’s examine this.

The Vedantic scriptures express discoveries made by the ancient rishis, and we use those scriptures to guide our own process of inquiry, in which we seek to personally discover what those rishis discovered.

But, in order to use those scriptures effectively, we need to have faith or trust in the value and validity of those scriptures.

On a vacation to Paris, you wouldn’t use a guidebook for sightseeing unless you trusted it’s contents to be accurate. Trusting the guidebook, you’d use it to find your way around.

That’s quite a good metaphor, showing how we first trust the validity of the scriptures, and then we use them in our search for knowledge.

It’s important to point out that our use of the word faith here is quite different from how it’s used in Western religion, where it suggests blind, unquestioned acceptance.

Instead of using the word faith to translate the word shraddha, it would be more accurate to say - trust in anticipation of personal verification.

We trust the scriptures to lead us to gain the knowledge of the existence and nature of God. And when we’ve gained this knowledge, the soundness of our trust will be borne out.

As we use the scriptures to guide our process of inquiry, we’ll sometimes encounter situations where the scriptures appear to be contradicted by logic and reason.

Whenever such apparent contradictions occur, they must be fully resolved. Any apparent contradictions can be fully resolved if we have access to a proper teacher and to authoritative commentaries on the scriptures.

This Vedantic approach stands in stark contrast to the Western religions, which often command, “You have to believe in the existence of God.”

In Vedanta, there’s absolutely no room for this kind of blind faith, with regard to the existence and nature of God, or anything else. In fact, blind faith can actually cause problems and be an obstacle to knowledge.

Many devout, deeply religious people are content to rely solely on their faith in God. They consider faith to be all that’s needed, so therefore, they have no interest in gaining personal knowledge of God’s existence and nature. They feel that the strength of their faith will always support and protect them, so, any further spiritual inquiry is unnecessary.

Unfortunately, such faith gives them a false sense of security.

Why?

Because no matter how strong their faith might be, it can be shaken under certain circumstances. Even if their faith can withstand the usual challenges and losses in life, at times of extreme misfortune, their faith could be overpowered. At such times, they might cry out in agony, “O God, where are you? Why aren’t you helping me?”

Sadly, devout people can sometimes be deserted by their faith in God at those very times when they are most in need of comfort and support.

No one’s faith is unshakable.

Faith is inherently fragile because it’s based on the strength of our minds, and our minds are always subject to moments of weakness.

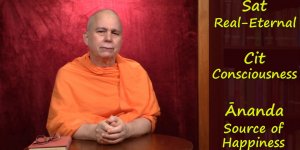

Knowledge, on the other hand, is unshakable. Knowledge is based on truth, not on the strength of our minds, so it’s always steadfast and dependable.

Imagine this: in the midst of terrible crisis or tragedy, would you have any doubts as to whether two plus two equals four?

Knowledge is unshakable and will never desert you.

So, in Vedanta, our goal is not to promote or instill any kind of belief with regard to the existence and nature of God. Instead, our goal is personal direct knowledge.

But then, is such knowledge really possible?

Well, if the ancient rishis could gain this knowledge, by following their teachings, we should also be able to do so.

Before we proceed, it’ll be really helpful if we give up our use of the word God. That word means different things to different people, and it often comes with lots of preconceptions and funny notions. So, let’s use the correct Sanskrit word instead. That word is Ishvara.

Ishvara can be defined as the source of the universe, the one because of whom everything exists.

Or, in the language of Western philosophy, Ishvara is the first cause or the uncaused cause.

Something cannot come from nothing. The universe is a something, therefore it must have come from something. That something because of which the universe exists is what we call Ishvara.

In this way, we can establish the existence of Ishvara as the first cause, the uncaused cause.

Ishvara’s existence can be simply established in this way, but to fully understand the nature of Ishvara requires much more inquiry.

In the language of Vedanta, the universe in which we live is the effect or karya for which Ishvara is the cause, the karana. In this way, Ishvara and the universe have a cause-effect relationship.

Cause-effect relationships imply, that for any karya, for any effect or created thing, there must be a suitable karana, a cause that has the capacity to produce that particular effect.

To understand this cause-effect relationship fully, we’ll have to distinguish between two different kinds of cause.

First, is the material cause, which is the material stuff from which an effect is made, like the vegetables, grains, and other ingredients needed to prepare a meal. In Sanskrit, material cause is known as upadana karana.

Second, is the efficient cause, which is the agent that produces the effect, like the cook who skillfully prepares a meal. Efficient cause is known as nimitta karana.

To understand these two different kinds of cause, consider a clay pot, which is a created object, an effect, karya.

For that clay pot, there must be a suitable material cause, upadana karana, which is clay, the material from which the pot is made.

There must also be suitable efficient cause, nimitta karana, which is the the potter, who has knowledge of pots and possesses the skill to make pots.

These two causes, the upadana karana and the nimitta karana, are both required to make or create anything.

For example, to make cloth, the required upadana karana is thread, and the required nimitta karana is a weaver who has knowledge of cloth as well as the skill of weaving.

In the same way, to make a complex computer chip containing millions of microscopic transistors, the required upadana karana is silicon, copper, and other materials. And the required nimitta karana is the team of scientists, engineers, and technicians who have knowledge of complex computer chips and the technical skills to manufacture them.

Now, let’s apply all this to understanding the nature of Ishvara, the creator of the universe.

The universe must have a suitable material cause, upadana karana, and a suitable efficient cause, nimitta karana.

Let’s take nimitta karana first. To make a pot, a potter is required who has both knowledge of pots and the skill to make pots.

In the same way, to create the universe, it’s creator, Ishvara, must possess both knowledge of the universe and the skill or power needed to create the universe.

From this analogy, we can conclude that Ishvara must be a conscious being, because only a conscious being can possess knowledge and skill.

Next we can ask, “What is the nature of the knowledge and skill that Ishvara possesses?”

Just as the potter has the particular skill of pot making, so too, Ishvara has the particular skill or power needed to create the universe. That skill or power is properly known as maya.

The word maya can be understood in several ways, but here, in this context, maya means, Ishvara’s power of creation, Ishvara’s creative capacity.

So, in the act of creation, Ishvara is the agent who wields maya, his power of creation, to bring the universe into existence.

In addition to the skill of pot making, the potter also possesses knowledge of pots. In the same way, in addition to having the power of maya, Ishvara also possesses all knowledge, knowledge of the entire universe.

That means, Ishvara has the intelligence necessary to fashion the universe in such a way that planets continue to orbit their stars without flying off into deep space, electrons stay in their atomic orbits without collapsing into the nucleus, and intelligent life can evolve on at least one planet amongst the billions of planets in the cosmos.

All this is evidence of Ishvara’s knowledge.

We can easily appreciate the great skill of distinguished artists in the beauty and magnificence of their artwork.

We can see the extensive knowledge of brilliant engineers in their mighty rockets and in their robotic rovers that have explored the surface of Mars.

In the same way, we can find Ishvara’s immeasurable knowledge and power in every speck and corner of this vast universe.

And nowhere is Ishvara’s knowledge and power more spectacularly manifest than in the intricate web of billions of neurons in our brains, that somehow makes it possible for us to ask, “What is all this? Where did it come from? And how did I get here?”

This presentation comes to an end here, after showing how Ishvara is the nimitta karana, the creator of the universe.

In the next presentation, we’ll examine the other cause, the upadana karana, the material cause for the universe.

Subscribe now to get unrestricted access to all resources, in all languages, throughout this web site!

Subscription Form

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Subscribe now to get unrestricted access to all resources, in all languages, throughout this web site!

Subscription Form