| Library / Literary Works |

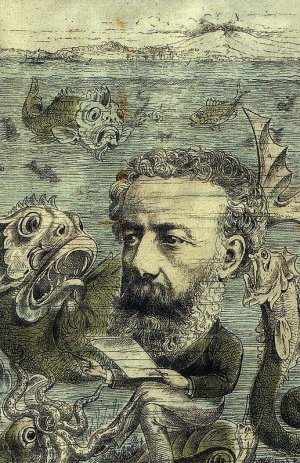

Jules Verne

Doctor Ox's Experiment

Table of Contents

1. How it is Useless to Seek, Even on the Best Maps, for the Small Town of Quiquendone.

2. In which the Burgomaster Van Tricasse and the Counsellor Niklausse Consult About the Affairs of the Town.

3. In which the Commissary Passauf Enters as Noisily as Unexpectedly.

4. In which Doctor Ox Reveals Himself as a Physiologist of the First Rank, and as an Audacious Experimentalist.

5. In which the Burgomaster and the Counsellor Pay a Visit to Doctor Ox, and what Follows.

6. In which Frantz Niklausse and Suzel Van Tricasse Form Certain Projects for the Future.

7. In which the Andantes Become Allegros, and the Allegros Vivaces.

8. In which the Ancient and Solemn German Waltz Becomes a Whirlwind.

9. In which Doctor Ox and Ygène, His Assistant, Say a Few Words.

10. In which it Will Be Seen that the Epidemic Invades the Entire Town, and what Effect it Produces.

11. In which the Quiquendonians Adopt a Heroic Resolution.

12. In which Ygène, the Assistant, Gives a Reasonable Piece of Advice, which is Eagerly Rejected by Doctor Ox.

13. In which it is Once More Proved that by Taking High Ground All Human Littlenesses May Be Overlooked.

14. In which Matters Go So Far that the Inhabitants of Quiquendone, the Reader, and Even the Author, Demand an Immediate Dénouement.

15. In which the Dénouement Takes Place.

16. In which the Intelligent Reader Sees that he has Guessed Correctly, Despite All the Author’s Precautions.

17. In which Doctor Ox’s Theory is Explained.

Chapter 1

How it is Useless to Seek, Even on the Best Maps, for the Small Town of Quiquendone.

If you try to find, on any map of Flanders, ancient or modern, the small town of Quiquendone, probably you will not succeed. Is Quiquendone, then, one of those towns which have disappeared? No. A town of the future? By no means. It exists in spite of geographies, and has done so for some eight or nine hundred years. It even numbers two thousand three hundred and ninety-three souls, allowing one soul to each inhabitant. It is situated thirteen and a half kilometres north-west of Oudenarde, and fifteen and a quarter kilometres south-east of Bruges, in the heart of Flanders. The Vaar, a small tributary of the Scheldt, passes beneath its three bridges, which are still covered with a quaint mediæval roof, like that at Tournay. An old château is to be seen there, the first stone of which was laid so long ago as 1197, by Count Baldwin, afterwards Emperor of Constantinople; and there is a Town Hall, with Gothic windows, crowned by a chaplet of battlements, and surrounded by a turreted belfry, which rises three hundred and fifty-seven feet above the soil. Every hour you may hear there a chime of five octaves, a veritable aerial piano, the renown of which surpasses that of the famous chimes of Bruges. Strangers — if any ever come to Quiquendone — do not quit the curious old town until they have visited its “Stadtholder’s Hall”, adorned by a full-length portrait of William of Nassau, by Brandon; the loft of the Church of Saint Magloire, a masterpiece of sixteenth century architecture; the cast-iron well in the spacious Place Saint Ernuph, the admirable ornamentation of which is attributed to the artist-blacksmith, Quentin Metsys; the tomb formerly erected to Mary of Burgundy, daughter of Charles the Bold, who now reposes in the Church of Notre Dame at Bruges; and so on. The principal industry of Quiquendone is the manufacture of whipped creams and barley-sugar on a large scale. It has been governed by the Van Tricasses, from father to son, for several centuries. And yet Quiquendone is not on the map of Flanders! Have the geographers forgotten it, or is it an intentional omission? That I cannot tell; but Quiquendone really exists; with its narrow streets, its fortified walls, its Spanish-looking houses, its market, and its burgomaster — so much so, that it has recently been the theatre of some surprising phenomena, as extraordinary and incredible as they are true, which are to be recounted in the present narration.

Surely there is nothing to be said or thought against the Flemings of Western Flanders. They are a well-to-do folk, wise, prudent, sociable, with even tempers, hospitable, perhaps a little heavy in conversation as in mind; but this does not explain why one of the most interesting towns of their district has yet to appear on modern maps.

This omission is certainly to be regretted. If only history, or in default of history the chronicles, or in default of chronicles the traditions of the country, made mention of Quiquendone! But no; neither atlases, guides, nor itineraries speak of it. M. Joanne himself, that energetic hunter after small towns, says not a word of it. It might be readily conceived that this silence would injure the commerce, the industries, of the town. But let us hasten to add that Quiquendone has neither industry nor commerce, and that it does very well without them. Its barley-sugar and whipped cream are consumed on the spot; none is exported. In short, the Quiquendonians have no need of anybody. Their desires are limited, their existence is a modest one; they are calm, moderate, phlegmatic — in a word, they are Flemings; such as are still to be met with sometimes between the Scheldt and the North Sea.

Chapter 2

In which the Burgomaster Van Tricasse and the Counsellor Niklausse Consult About the Affairs of the Town.

“You think so?” asked the burgomaster.

“I— think so,” replied the counsellor, after some minutes of silence.

“You see, we must not act hastily,” resumed the burgomaster.

“We have been talking over this grave matter for ten years,” replied the Counsellor Niklausse, “and I confess to you, my worthy Van Tricasse, that I cannot yet take it upon myself to come to a decision.”

“I quite understand your hesitation,” said the burgomaster, who did not speak until after a good quarter of an hour of reflection, “I quite understand it, and I fully share it. We shall do wisely to decide upon nothing without a more careful examination of the question.”

“It is certain,” replied Niklausse, “that this post of civil commissary is useless in so peaceful a town as Quiquendone.”

“Our predecessor,” said Van Tricasse gravely, “our predecessor never said, never would have dared to say, that anything is certain. Every affirmation is subject to awkward qualifications.”

The counsellor nodded his head slowly in token of assent; then he remained silent for nearly half an hour. After this lapse of time, during which neither the counsellor nor the burgomaster moved so much as a finger, Niklausse asked Van Tricasse whether his predecessor — of some twenty years before — had not thought of suppressing this office of civil commissary, which each year cost the town of Quiquendone the sum of thirteen hundred and seventy-five francs and some centimes.

“I believe he did,” replied the burgomaster, carrying his hand with majestic deliberation to his ample brow; “but the worthy man died without having dared to make up his mind, either as to this or any other administrative measure. He was a sage. Why should I not do as he did?”

Counsellor Niklausse was incapable of originating any objection to the burgomaster’s opinion.

“The man who dies,” added Van Tricasse solemnly, “without ever having decided upon anything during his life, has very nearly attained to perfection.”

This said, the burgomaster pressed a bell with the end of his little finger, which gave forth a muffled sound, which seemed less a sound than a sigh. Presently some light steps glided softly across the tile floor. A mouse would not have made less noise, running over a thick carpet. The door of the room opened, turning on its well-oiled hinges. A young girl, with long blonde tresses, made her appearance. It was Suzel Van Tricasse, the burgomaster’s only daughter. She handed her father a pipe, filled to the brim, and a small copper brazier, spoke not a word, and disappeared at once, making no more noise at her exit than at her entrance.

The worthy burgomaster lighted his pipe, and was soon hidden in a cloud of bluish smoke, leaving Counsellor Niklausse plunged in the most absorbing thought.

The room in which these two notable personages, charged with the government of Quiquendone, were talking, was a parlour richly adorned with carvings in dark wood. A lofty fireplace, in which an oak might have been burned or an ox roasted, occupied the whole of one of the sides of the room; opposite to it was a trellised window, the painted glass of which toned down the brightness of the sunbeams. In an antique frame above the chimney-piece appeared the portrait of some worthy man, attributed to Memling, which no doubt represented an ancestor of the Van Tricasses, whose authentic genealogy dates back to the fourteenth century, the period when the Flemings and Guy de Dampierre were engaged in wars with the Emperor Rudolph of Hapsburgh.

This parlour was the principal apartment of the burgomaster’s house, which was one of the pleasantest in Quiquendone. Built in the Flemish style, with all the abruptness, quaintness, and picturesqueness of Pointed architecture, it was considered one of the most curious monuments of the town. A Carthusian convent, or a deaf and dumb asylum, was not more silent than this mansion. Noise had no existence there; people did not walk, but glided about in it; they did not speak, they murmured. There was not, however, any lack of women in the house, which, in addition to the burgomaster Van Tricasse himself, sheltered his wife, Madame Brigitte Van Tricasse, his daughter, Suzel Van Tricasse, and his domestic, Lotchè Janshéu. We may also mention the burgomaster’s sister, Aunt Hermance, an elderly maiden who still bore the nickname of Tatanémance, which her niece Suzel had given her when a child. But in spite of all these elements of discord and noise, the burgomaster’s house was as calm as a desert.

The burgomaster was some fifty years old, neither fat nor lean, neither short nor tall, neither rubicund nor pale, neither gay nor sad, neither contented nor discontented, neither energetic nor dull, neither proud nor humble, neither good nor bad, neither generous nor miserly, neither courageous nor cowardly, neither too much nor too little of anything — a man notably moderate in all respects, whose invariable slowness of motion, slightly hanging lower jaw, prominent eyebrows, massive forehead, smooth as a copper plate and without a wrinkle, would at once have betrayed to a physiognomist that the burgomaster Van Tricasse was phlegm personified. Never, either from anger or passion, had any emotion whatever hastened the beating of this man’s heart, or flushed his face; never had his pupils contracted under the influence of any irritation, however ephemeral. He invariably wore good clothes, neither too large nor too small, which he never seemed to wear out. He was shod with large square shoes with triple soles and silver buckles, which lasted so long that his shoemaker was in despair. Upon his head he wore a large hat which dated from the period when Flanders was separated from Holland, so that this venerable masterpiece was at least forty years old. But what would you have? It is the passions which wear out body as well as soul, the clothes as well as the body; and our worthy burgomaster, apathetic, indolent, indifferent, was passionate in nothing. He wore nothing out, not even himself, and he considered himself the very man to administer the affairs of Quiquendone and its tranquil population.

The town, indeed, was not less calm than the Van Tricasse mansion. It was in this peaceful dwelling that the burgomaster reckoned on attaining the utmost limit of human existence, after having, however, seen the good Madame Brigitte Van Tricasse, his wife, precede him to the tomb, where, surely, she would not find a more profound repose than that she had enjoyed on earth for sixty years.

This demands explanation.

The Van Tricasse family might well call itself the “Jeannot family.” This is why:—

Every one knows that the knife of this typical personage is as celebrated as its proprietor, and not less incapable of wearing out, thanks to the double operation, incessantly repeated, of replacing the handle when it is worn out, and the blade when it becomes worthless. A precisely similar operation had been going on from time immemorial in the Van Tricasse family, to which Nature had lent herself with more than usual complacency. From 1340 it had invariably happened that a Van Tricasse, when left a widower, had remarried a Van Tricasse younger than himself; who, becoming in turn a widow, had married again a Van Tricasse younger than herself; and so on, without a break in the continuity, from generation to generation. Each died in his or her turn with mechanical regularity. Thus the worthy Madame Brigitte Van Tricasse had now her second husband; and, unless she violated her every duty, would precede her spouse — he being ten years younger than herself — to the other world, to make room for a new Madame Van Tricasse. Upon this the burgomaster calmly counted, that the family tradition might not be broken. Such was this mansion, peaceful and silent, of which the doors never creaked, the windows never rattled, the floors never groaned, the chimneys never roared, the weathercocks never grated, the furniture never squeaked, the locks never clanked, and the occupants never made more noise than their shadows. The god Harpocrates would certainly have chosen it for the Temple of Silence.

Chapter 3

In which the Commissary Passauf Enters as Noisily as Unexpectedly.

When the interesting conversation which has been narrated began, it was a quarter before three in the afternoon. It was at a quarter before four that Van Tricasse lighted his enormous pipe, which could hold a quart of tobacco, and it was at thirty-five minutes past five that he finished smoking it.

All this time the two comrades did not exchange a single word.

About six o’clock the counsellor, who had a habit of speaking in a very summary manner, resumed in these words,—

“So we decide —”

“To decide nothing,” replied the burgomaster.

“I think, on the whole, that you are right, Van Tricasse.”

“I think so too, Niklausse. We will take steps with reference to the civil commissary when we have more light on the subject — later on. There is no need for a month yet.”

“Nor even for a year,” replied Niklausse, unfolding his pocket-handkerchief and calmly applying it to his nose.

There was another silence of nearly a quarter of an hour. Nothing disturbed this repeated pause in the conversation; not even the appearance of the house-dog Lento, who, not less phlegmatic than his master, came to pay his respects in the parlour. Noble dog!— a model for his race. Had he been made of pasteboard, with wheels on his paws, he would not have made less noise during his stay.

Towards eight o’clock, after Lotchè had brought the antique lamp of polished glass, the burgomaster said to the counsellor,—

“We have no other urgent matter to consider?”

“No, Van Tricasse; none that I know of.”

“Have I not been told, though,” asked the burgomaster, “that the tower of the Oudenarde gate is likely to tumble down?”

“Ah!” replied the counsellor; “really, I should not be astonished if it fell on some passer-by any day.”

“Oh! before such a misfortune happens I hope we shall have come to a decision on the subject of this tower.”

“I hope so, Van Tricasse.”

“There are more pressing matters to decide.”

“No doubt; the question of the leather-market, for instance.”

“What, is it still burning?”

“Still burning, and has been for the last three weeks.”

“Have we not decided in council to let it burn?”

“Yes, Van Tricasse — on your motion.”

“Was not that the surest and simplest way to deal with it?”

“Without doubt.”

“Well, let us wait. Is that all?”

“All,” replied the counsellor, scratching his head, as if to assure himself that he had not forgotten anything important.

“Ah!” exclaimed the burgomaster, “haven’t you also heard something of an escape of water which threatens to inundate the low quarter of Saint Jacques?”

“I have. It is indeed unfortunate that this escape of water did not happen above the leather-market! It would naturally have checked the fire, and would thus have saved us a good deal of discussion.”

“What can you expect, Niklausse? There is nothing so illogical as accidents. They are bound by no rules, and we cannot profit by one, as we might wish, to remedy another.”

It took Van Tricasse’s companion some time to digest this fine observation.

“Well, but,” resumed the Counsellor Niklausse, after the lapse of some moments, “we have not spoken of our great affair!”

“What great affair? Have we, then, a great affair?” asked the burgomaster.

“No doubt. About lighting the town.”

“O yes. If my memory serves me, you are referring to the lighting plan of Doctor Ox.”

“Precisely.”

“It is going on, Niklausse,” replied the burgomaster. “They are already laying the pipes, and the works are entirely completed.”

“Perhaps we have hurried a little in this matter,” said the counsellor, shaking his head.

“Perhaps. But our excuse is, that Doctor Ox bears the whole expense of his experiment. It will not cost us a sou.”

“That, true enough, is our excuse. Moreover, we must advance with the age. If the experiment succeeds, Quiquendone will be the first town in Flanders to be lighted with the oxy — What is the gas called?”

“Oxyhydric gas.”

“Well, oxyhydric gas, then.”

At this moment the door opened, and Lotchè came in to tell the burgomaster that his supper was ready.

Counsellor Niklausse rose to take leave of Van Tricasse, whose appetite had been stimulated by so many affairs discussed and decisions taken; and it was agreed that the council of notables should be convened after a reasonably long delay, to determine whether a decision should be provisionally arrived at with reference to the really urgent matter of the Oudenarde gate.

The two worthy administrators then directed their steps towards the street-door, the one conducting the other. The counsellor, having reached the last step, lighted a little lantern to guide him through the obscure streets of Quiquendone, which Doctor Ox had not yet lighted. It was a dark October night, and a light fog overshadowed the town.

Niklausse’s preparations for departure consumed at least a quarter of an hour; for, after having lighted his lantern, he had to put on his big cow-skin socks and his sheep-skin gloves; then he put up the furred collar of his overcoat, turned the brim of his felt hat down over his eyes, grasped his heavy crow-beaked umbrella, and got ready to start.

When Lotchè, however, who was lighting her master, was about to draw the bars of the door, an unexpected noise arose outside.

Yes! Strange as the thing seems, a noise — a real noise, such as the town had certainly not heard since the taking of the donjon by the Spaniards in 1513 — terrible noise, awoke the long-dormant echoes of the venerable Van Tricasse mansion.

Some one knocked heavily upon this door, hitherto virgin to brutal touch! Redoubled knocks were given with some blunt implement, probably a knotty stick, wielded by a vigorous arm. With the strokes were mingled cries and calls. These words were distinctly heard:—

“Monsieur Van Tricasse! Monsieur the burgomaster! Open, open quickly!”

The burgomaster and the counsellor, absolutely astounded, looked at each other speechless.

This passed their comprehension. If the old culverin of the château, which had not been used since 1385, had been let off in the parlour, the dwellers in the Van Tricasse mansion would not have been more dumbfoundered.

Meanwhile, the blows and cries were redoubled. Lotchè, recovering her coolness, had plucked up courage to speak.

“Who is there?”

“It is I! I! I!”

“Who are you?”

“The Commissary Passauf!”

The Commissary Passauf! The very man whose office it had been contemplated to suppress for ten years. What had happened, then? Could the Burgundians have invaded Quiquendone, as they did in the fourteenth century? No event of less importance could have so moved Commissary Passauf, who in no degree yielded the palm to the burgomaster himself for calmness and phlegm.

On a sign from Van Tricasse — for the worthy man could not have articulated a syllable — the bar was pushed back and the door opened.

Commissary Passauf flung himself into the antechamber. One would have thought there was a hurricane.

“What’s the matter, Monsieur the commissary?” asked Lotchè, a brave woman, who did not lose her head under the most trying circumstances.

“What’s the matter!” replied Passauf, whose big round eyes expressed a genuine agitation. “The matter is that I have just come from Doctor Ox’s, who has been holding a reception, and that there —”

“There?”

“There I have witnessed such an altercation as — Monsieur the burgomaster, they have been talking politics!”

“Politics!” repeated Van Tricasse, running his fingers through his wig.

“Politics!” resumed Commissary Passauf, “which has not been done for perhaps a hundred years at Quiquendone. Then the discussion got warm, and the advocate, André Schut, and the doctor, Dominique Custos, became so violent that it may be they will call each other out.”

“Call each other out!” cried the counsellor. “A duel! A duel at Quiquendone! And what did Advocate Schut and Doctor Gustos say?”

“Just this: ‘Monsieur advocate,’ said the doctor to his adversary, ‘you go too far, it seems to me, and you do not take sufficient care to control your words!’”

The Burgomaster Van Tricasse clasped his hands — the counsellor turned pale and let his lantern fall — the commissary shook his head. That a phrase so evidently irritating should be pronounced by two of the principal men in the country!

“This Doctor Custos,” muttered Van Tricasse, “is decidedly a dangerous man — a hare-brained fellow! Come, gentlemen!”

On this, Counsellor Niklausse and the commissary accompanied the burgomaster into the parlour.

Chapter 4

In which Doctor Ox Reveals Himself as a Physiologist of the First Rank, and as an Audacious Experimentalist.

Who, then, was this personage, known by the singular name of Doctor Ox?

An original character for certain, but at the same time a bold savant, a physiologist, whose works were known and highly estimated throughout learned Europe, a happy rival of the Davys, the Daltons, the Bostocks, the Menzies, the Godwins, the Vierordts — of all those noble minds who have placed physiology among the highest of modern sciences.

Doctor Ox was a man of medium size and height, aged —: but we cannot state his age, any more than his nationality. Besides, it matters little; let it suffice that he was a strange personage, impetuous and hot-blooded, a regular oddity out of one of Hoffmann’s volumes, and one who contrasted amusingly enough with the good people of Quiquendone. He had an imperturbable confidence both in himself and in his doctrines. Always smiling, walking with head erect and shoulders thrown back in a free and unconstrained manner, with a steady gaze, large open nostrils, a vast mouth which inhaled the air in liberal draughts, his appearance was far from unpleasing. He was full of animation, well proportioned in all parts of his bodily mechanism, with quicksilver in his veins, and a most elastic step. He could never stop still in one place, and relieved himself with impetuous words and a superabundance of gesticulations.

Was Doctor Ox rich, then, that he should undertake to light a whole town at his expense? Probably, as he permitted himself to indulge in such extravagance,— and this is the only answer we can give to this indiscreet question.

Doctor Ox had arrived at Quiquendone five months before, accompanied by his assistant, who answered to the name of Gédéon Ygène; a tall, dried-up, thin man, haughty, but not less vivacious than his master.

And next, why had Doctor Ox made the proposition to light the town at his own expense? Why had he, of all the Flemings, selected the peaceable Quiquendonians, to endow their town with the benefits of an unheard-of system of lighting? Did he not, under this pretext, design to make some great physiological experiment by operating in anima vili? In short, what was this original personage about to attempt? We know not, as Doctor Ox had no confidant except his assistant Ygène, who, moreover, obeyed him blindly.

In appearance, at least, Doctor Ox had agreed to light the town, which had much need of it, “especially at night,” as Commissary Passauf wittily said. Works for producing a lighting gas had accordingly been established; the gasometers were ready for use, and the main pipes, running beneath the street pavements, would soon appear in the form of burners in the public edifices and the private houses of certain friends of progress. Van Tricasse and Niklausse, in their official capacity, and some other worthies, thought they ought to allow this modern light to be introduced into their dwellings.

If the reader has not forgotten, it was said, during the long conversation of the counsellor and the burgomaster, that the lighting of the town was to be achieved, not by the combustion of common carburetted hydrogen, produced by distilling coal, but by the use of a more modern and twenty-fold more brilliant gas, oxyhydric gas, produced by mixing hydrogen and oxygen.

The doctor, who was an able chemist as well as an ingenious physiologist, knew how to obtain this gas in great quantity and of good quality, not by using manganate of soda, according to the method of M. Tessié du Motay, but by the direct decomposition of slightly acidulated water, by means of a battery made of new elements, invented by himself. Thus there were no costly materials, no platinum, no retorts, no combustibles, no delicate machinery to produce the two gases separately. An electric current was sent through large basins full of water, and the liquid was decomposed into its two constituent parts, oxygen and hydrogen. The oxygen passed off at one end; the hydrogen, of double the volume of its late associate, at the other. As a necessary precaution, they were collected in separate reservoirs, for their mixture would have produced a frightful explosion if it had become ignited. Thence the pipes were to convey them separately to the various burners, which would be so placed as to prevent all chance of explosion. Thus a remarkably brilliant flame would be obtained, whose light would rival the electric light, which, as everybody knows, is, according to Cassellmann’s experiments, equal to that of eleven hundred and seventy-one wax candles,— not one more, nor one less.

It was certain that the town of Quiquendone would, by this liberal contrivance, gain a splendid lighting; but Doctor Ox and his assistant took little account of this, as will be seen in the sequel.

The day after that on which Commissary Passauf had made his noisy entrance into the burgomaster’s parlour, Gédéon Ygène and Doctor Ox were talking in the laboratory which both occupied in common, on the ground-floor of the principal building of the gas-works.

“Well, Ygène, well,” cried the doctor, rubbing his hands. “You saw, at my reception yesterday, the cool-bloodedness of these worthy Quiquendonians. For animation they are midway between sponges and coral! You saw them disputing and irritating each other by voice and gesture? They are already metamorphosed, morally and physically! And this is only the beginning. Wait till we treat them to a big dose!”

“Indeed, master,” replied Ygène, scratching his sharp nose with the end of his forefinger, “the experiment begins well, and if I had not prudently closed the supply-tap, I know not what would have happened.”

“You heard Schut, the advocate, and Custos, the doctor?” resumed Doctor Ox. “The phrase was by no means ill-natured in itself, but, in the mouth of a Quiquendonian, it is worth all the insults which the Homeric heroes hurled at each other before drawing their swords, Ah, these Flemings! You’ll see what we shall do some day!”

“We shall make them ungrateful,” replied Ygène, in the tone of a man who esteems the human race at its just worth.

“Bah!” said the doctor; “what matters it whether they think well or ill of us, so long as our experiment succeeds?”

“Besides,” returned the assistant, smiling with a malicious expression, “is it not to be feared that, in producing such an excitement in their respiratory organs, we shall somewhat injure the lungs of these good people of Quiquendone?”

“So much the worse for them! It is in the interests of science. What would you say if the dogs or frogs refused to lend themselves to the experiments of vivisection?”

It is probable that if the frogs and dogs were consulted, they would offer some objection; but Doctor Ox imagined that he had stated an unanswerable argument, for he heaved a great sigh of satisfaction.

“After all, master, you are right,” replied Ygène, as if quite convinced. “We could not have hit upon better subjects than these people of Quiquendone for our experiment.”

“We — could — not,” said the doctor, slowly articulating each word.

“Have you felt the pulse of any of them?”

“Some hundreds.”

“And what is the average pulsation you found?”

“Not fifty per minute. See — this is a town where there has not been the shadow of a discussion for a century, where the carmen don’t swear, where the coachmen don’t insult each other, where horses don’t run away, where the dogs don’t bite, where the cats don’t scratch,— a town where the police-court has nothing to do from one year’s end to another,— a town where people do not grow enthusiastic about anything, either about art or business,— a town where the gendarmes are a sort of myth, and in which an indictment has not been drawn up for a hundred years,— a town, in short, where for three centuries nobody has struck a blow with his fist or so much as exchanged a slap in the face! You see, Ygène, that this cannot last, and that we must change it all.”

“Perfectly! perfectly!” cried the enthusiastic assistant; “and have you analyzed the air of this town, master?”

“I have not failed to do so. Seventy-nine parts of azote and twenty-one of oxygen, carbonic acid and steam in a variable quantity. These are the ordinary proportions.”

“Good, doctor, good!” replied Ygène. “The experiment will be made on a large scale, and will be decisive.”

“And if it is decisive,” added Doctor Ox triumphantly, “we shall reform the world!”

Chapter 5

In which the Burgomaster and the Counsellor Pay a Visit to Doctor Ox, and what Follows.

The Counsellor Niklausse and the Burgomaster Van Tricasse at last knew what it was to have an agitated night. The grave event which had taken place at Doctor Ox’s house actually kept them awake. What consequences was this affair destined to bring about? They could not imagine. Would it be necessary for them to come to a decision? Would the municipal authority, whom they represented, be compelled to interfere? Would they be obliged to order arrests to be made, that so great a scandal should not be repeated? All these doubts could not but trouble these soft natures; and on that evening, before separating, the two notables had “decided” to see each other the next day.

On the next morning, then, before dinner, the Burgomaster Van Tricasse proceeded in person to the Counsellor Niklausse’s house. He found his friend more calm. He himself had recovered his equanimity.

“Nothing new?” asked Van Tricasse.

“Nothing new since yesterday,” replied Niklausse.

“And the doctor, Dominique Custos?”

“I have not heard anything, either of him or of the advocate, André Schut.”

After an hour’s conversation, which consisted of three remarks which it is needless to repeat, the counsellor and the burgomaster had resolved to pay a visit to Doctor Ox, so as to draw from him, without seeming to do so, some details of the affair.

Contrary to all their habits, after coming to this decision the two notables set about putting it into execution forthwith. They left the house and directed their steps towards Doctor Ox’s laboratory, which was situated outside the town, near the Oudenarde gate — the gate whose tower threatened to fall in ruins.

They did not take each other’s arms, but walked side by side, with a slow and solemn step, which took them forward but thirteen inches per second. This was, indeed, the ordinary gait of the Quiquendonians, who had never, within the memory of man, seen any one run across the streets of their town.

From time to time the two notables would stop at some calm and tranquil crossway, or at the end of a quiet street, to salute the passers-by.

“Good morning, Monsieur the burgomaster,” said one.

“Good morning, my friend,” responded Van Tricasse.

“Anything new, Monsieur the counsellor?” asked another.

“Nothing new,” answered Niklausse.

But by certain agitated motions and questioning looks, it was evident that the altercation of the evening before was known throughout the town. Observing the direction taken by Van Tricasse, the most obtuse Quiquendonians guessed that the burgomaster was on his way to take some important step. The Custos and Schut affair was talked of everywhere, but the people had not yet come to the point of taking the part of one or the other. The Advocate Schut, having never had occasion to plead in a town where attorneys and bailiffs only existed in tradition, had, consequently, never lost a suit. As for the Doctor Custos, he was an honourable practitioner, who, after the example of his fellow-doctors, cured all the illnesses of his patients, except those of which they died — a habit unhappily acquired by all the members of all the faculties in whatever country they may practise.

On reaching the Oudenarde gate, the counsellor and the burgomaster prudently made a short detour, so as not to pass within reach of the tower, in case it should fall; then they turned and looked at it attentively.

“I think that it will fall,” said Van Tricasse.

“I think so too,” replied Niklausse.

“Unless it is propped up,” added Van Tricasse. “But must it be propped up? That is the question.”

“That is — in fact — the question.”

Some moments after, they reached the door of the gasworks.

“Can we see Doctor Ox?” they asked.

Doctor Ox could always be seen by the first authorities of the town, and they were at once introduced into the celebrated physiologist’s study.

Perhaps the two notables waited for the doctor at least an hour; at least it is reasonable to suppose so, as the burgomaster — a thing that had never before happened in his life — betrayed a certain amount of impatience, from which his companion was not exempt.

Doctor Ox came in at last, and began to excuse himself for having kept them waiting; but he had to approve a plan for the gasometer, rectify some of the machinery — But everything was going on well! The pipes intended for the oxygen were already laid. In a few months the town would be splendidly lighted. The two notables might even now see the orifices of the pipes which were laid on in the laboratory.

Then the doctor begged to know to what he was indebted for the honour of this visit.

“Only to see you, doctor; to see you,” replied Van Tricasse. “It is long since we have had the pleasure. We go abroad but little in our good town of Quiquendone. We count our steps and measure our walks. We are happy when nothing disturbs the uniformity of our habits.”

Niklausse looked at his friend. His friend had never said so much at once — at least, without taking time, and giving long intervals between his sentences. It seemed to him that Van Tricasse expressed himself with a certain volubility, which was by no means common with him. Niklausse himself experienced a kind of irresistible desire to talk.

As for Doctor Ox, he looked at the burgomaster with sly attention.

Van Tricasse, who never argued until he had snugly ensconced himself in a spacious armchair, had risen to his feet. I know not what nervous excitement, quite foreign to his temperament, had taken possession of him. He did not gesticulate as yet, but this could not be far off. As for the counsellor, he rubbed his legs, and breathed with slow and long gasps. His look became animated little by little, and he had “decided” to support at all hazards, if need be, his trusty friend the burgomaster.

Van Tricasse got up and took several steps; then he came back, and stood facing the doctor.

“And in how many months,” he asked in a somewhat emphatic tome, “do you say that your work will be finished?”

“In three or four months, Monsieur the burgomaster,” replied Doctor Ox.

“Three or four months,— it’s a very long time!” said Van Tricasse.

“Altogether too long!” added Niklausse, who, not being able to keep his seat, rose also.

“This lapse of time is necessary to complete our work,” returned Doctor Ox. “The workmen, whom we have had to choose in Quiquendone, are not very expeditious.”

“How not expeditious?” cried the burgomaster, who seemed to take the remark as personally offensive.

“No, Monsieur Van Tricasse,” replied Doctor Ox obstinately. “A French workman would do in a day what it takes ten of your workmen to do; you know, they are regular Flemings!”

“Flemings!” cried the counsellor, whose fingers closed together. “In what sense, sir, do you use that word?”

“Why, in the amiable sense in which everybody uses it,” replied Doctor Ox, smiling.

“Ah, but doctor,” said the burgomaster, pacing up and down the room, “I don’t like these insinuations. The workmen of Quiquendone are as efficient as those of any other town in the world, you must know; and we shall go neither to Paris nor London for our models! As for your project, I beg you to hasten its execution. Our streets have been unpaved for the putting down of your conduit-pipes, and it is a hindrance to traffic. Our trade will begin to suffer, and I, being the responsible authority, do not propose to incur reproaches which will be but too just.”

Worthy burgomaster! He spoke of trade, of traffic, and the wonder was that those words, to which he was quite unaccustomed, did not scorch his lips. What could be passing in his mind?

“Besides,” added Niklausse, “the town cannot be deprived of light much longer.”

“But,” urged Doctor Ox, “a town which has been unlighted for eight or nine hundred years —”

“All the more necessary is it,” replied the burgomaster, emphasizing his words. “Times alter, manners alter! The world advances, and we do not wish to remain behind. We desire our streets to be lighted within a month, or you must pay a large indemnity for each day of delay; and what would happen if, amid the darkness, some affray should take place?”

“No doubt,” cried Niklausse. “It requires but a spark to inflame a Fleming! Fleming! Flame!”

“Apropos of this,” said the burgomaster, interrupting his friend, “Commissary Passauf, our chief of police, reports to us that a discussion took place in your drawing-room last evening, Doctor Ox. Was he wrong in declaring that it was a political discussion?”

“By no means, Monsieur the burgomaster,” replied Doctor Ox, who with difficulty repressed a sigh of satisfaction.

“So an altercation did take place between Dominique Gustos and André Schut?”

“Yes, counsellor; but the words which passed were not of grave import.”

“Not of grave import!” cried the burgomaster. “Not of grave import, when one man tells another that he does not measure the effect of his words! But of what stuff are you made, monsieur? Do you not know that in Quiquendone nothing more is needed to bring about extremely disastrous results? But monsieur, if you, or any one else, presume to speak thus to me —”

“Or to me,” added Niklausse.

As they pronounced these words with a menacing air, the two notables, with folded arms and bristling air, confronted Doctor Ox, ready to do him some violence, if by a gesture, or even the expression of his eye, he manifested any intention of contradicting them.

But the doctor did not budge.

“At all events, monsieur,” resumed the burgomaster, “I propose to hold you responsible for what passes in your house. I am bound to insure the tranquillity of this town, and I do not wish it to be disturbed. The events of last evening must not be repeated, or I shall do my duty, sir! Do you hear? Then reply, sir.”

The burgomaster, as he spoke, under the influence of extraordinary excitement, elevated his voice to the pitch of anger. He was furious, the worthy Van Tricasse, and might certainly be heard outside. At last, beside himself, and seeing that Doctor Ox did not reply to his challenge, “Come, Niklausse,” said he.

And, slamming the door with a violence which shook the house, the burgomaster drew his friend after him.

Little by little, when they had taken twenty steps on their road, the worthy notables grew more calm. Their pace slackened, their gait became less feverish. The flush on their faces faded away; from being crimson, they became rosy. A quarter of an hour after quitting the gasworks, Van Tricasse said softly to Niklausse, “An amiable man, Doctor Ox! It is always a pleasure to see him!”

Chapter 6

In which Frantz Niklausse and Suzel Van Tricasse Form Certain Projects for the Future.

Our readers know that the burgomaster had a daughter, Suzel But, shrewd as they may be, they cannot have divined that the counsellor Niklausse had a son, Frantz; and had they divined this, nothing could have led them to imagine that Frantz was the betrothed lover of Suzel. We will add that these young people were made for each other, and that they loved each other, as folks did love at Quiquendone.

It must not be thought that young hearts did not beat in this exceptional place; only they beat with a certain deliberation. There were marriages there, as in every other town in the world; but they took time about it. Betrothed couples, before engaging in these terrible bonds, wished to study each other; and these studies lasted at least ten years, as at college. It was rare that any one was “accepted” before this lapse of time.

Yes, ten years! The courtships last ten years! And is it, after all, too long, when the being bound for life is in consideration? One studies ten years to become an engineer or physician, an advocate or attorney, and should less time be spent in acquiring the knowledge to make a good husband? Is it not reasonable? and, whether due to temperament or reason with them, the Quiquendonians seem to us to be in the right in thus prolonging their courtship. When marriages in other more lively and excitable cities are seen taking place within a few months, we must shrug our shoulders, and hasten to send our boys to the schools and our daughters to the pensions of Quiquendone.

For half a century but a single marriage was known to have taken place after the lapse of two years only of courtship, and that turned out badly!

Frantz Niklausse, then, loved Suzel Van Tricasse, but quietly, as a man would love when he has ten years before him in which to obtain the beloved object. Once every week, at an hour agreed upon, Frantz went to fetch Suzel, and took a walk with her along the banks of the Vaar. He took good care to carry his fishing-tackle, and Suzel never forgot her canvas, on which her pretty hands embroidered the most unlikely flowers.

Frantz was a young man of twenty-two, whose cheeks betrayed a soft, peachy down, and whose voice had scarcely a compass of one octave.

As for Suzel, she was blonde and rosy. She was seventeen, and did not dislike fishing. A singular occupation this, however, which forces you to struggle craftily with a barbel. But Frantz loved it; the pastime was congenial to his temperament. As patient as possible, content to follow with his rather dreamy eye the cork which bobbed on the top of the water, he knew how to wait; and when, after sitting for six hours, a modest barbel, taking pity on him, consented at last to be caught, he was happy — but he knew how to control his emotion.

On this day the two lovers — one might say, the two betrothed — were seated upon the verdant bank. The limpid Vaar murmured a few feet below them. Suzel quietly drew her needle across the canvas. Frantz automatically carried his line from left to right, then permitted it to descend the current from right to left. The fish made capricious rings in the water, which crossed each other around the cork, while the hook hung useless near the bottom.

From time to time Frantz would say, without raising his eyes,—

“I think I have a bite, Suzel.”

“Do you think so, Frantz?” replied Suzel, who, abandoning her work for an instant, followed her lover’s line with earnest eye.

“N-no,” resumed Frantz; “I thought I felt a little twitch; I was mistaken.”

“You will have a bite, Frantz,” replied Suzel, in her pure, soft voice. “But do not forget to strike at the right moment. You are always a few seconds too late, and the barbel takes advantage to escape.”

“Would you like to take my line, Suzel?”

“Willingly, Frantz.”

“Then give me your canvas. We shall see whether I am more adroit with the needle than with the hook.”

And the young girl took the line with trembling hand, while her swain plied the needle across the stitches of the embroidery. For hours together they thus exchanged soft words, and their hearts palpitated when the cork bobbed on the water. Ah, could they ever forget those charming hours, during which, seated side by side, they listened to the murmurs of the river?

The sun was fast approaching the western horizon, and despite the combined skill of Suzel and Frantz, there had not been a bite. The barbels had not shown themselves complacent, and seemed to scoff at the two young people, who were too just to bear them malice.

“We shall be more lucky another time, Frantz,” said Suzel, as the young angler put up his still virgin hook.

“Let us hope so,” replied Frantz.

Then walking side by side, they turned their steps towards the house, without exchanging a word, as mute as their shadows which stretched out before them. Suzel became very, very tall under the oblique rays of the setting sun. Frantz appeared very, very thin, like the long rod which he held in his hand.

They reached the burgomaster’s house. Green tufts of grass bordered the shining pavement, and no one would have thought of tearing them away, for they deadened the noise made by the passers-by.

As they were about to open the door, Frantz thought it his duty to say to Suzel,—

“You know, Suzel, the great day is approaching?”

“It is indeed, Frantz,” replied the young girl, with downcast eyes.

“Yes,” said Frantz, “in five or six years —”

“Good-bye, Frantz,” said Suzel.

“Good-bye, Suzel,” replied Frantz.

And, after the door had been closed, the young man resumed the way to his father’s house with a calm and equal pace.

Chapter 7

In which the Andantes Become Allegros, and the Allegros Vivaces.

The agitation caused by the Schut and Custos affair had subsided. The affair led to no serious consequences. It appeared likely that Quiquendone would return to its habitual apathy, which that unexpected event had for a moment disturbed.

Meanwhile, the laying of the pipes destined to conduct the oxyhydric gas into the principal edifices of the town was proceeding rapidly. The main pipes and branches gradually crept beneath the pavements. But the burners were still wanting; for, as it required delicate skill to make them, it was necessary that they should be fabricated abroad. Doctor Ox was here, there, and everywhere; neither he nor Ygène, his assistant, lost a moment, but they urged on the workmen, completed the delicate mechanism of the gasometer, fed day and night the immense piles which decomposed the water under the influence of a powerful electric current. Yes, the doctor was already making his gas, though the pipe-laying was not yet done; a fact which, between ourselves, might have seemed a little singular. But before long,— at least there was reason to hope so,— before long Doctor Ox would inaugurate the splendours of his invention in the theatre of the town.

For Quiquendone possessed a theatre — a really fine edifice, in truth — the interior and exterior arrangement of which combined every style of architecture. It was at once Byzantine, Roman, Gothic, Renaissance, with semicircular doors, Pointed windows, Flamboyant rose-windows, fantastic bell-turrets,— in a word, a specimen of all sorts, half a Parthenon, half a Parisian Grand Café. Nor was this surprising, the theatre having been commenced under the burgomaster Ludwig Van Tricasse, in 1175, and only finished in 1837, under the burgomaster Natalis Van Tricasse. It had required seven hundred years to build it, and it had, been successively adapted to the architectural style in vogue in each period. But for all that it was an imposing structure; the Roman pillars and Byzantine arches of which would appear to advantage lit up by the oxyhydric gas.

Pretty well everything was acted at the theatre of Quiquendone; but the opera and the opera comique were especially patronized. It must, however, be added that the composers would never have recognized their own works, so entirely changed were the “movements” of the music.

In short, as nothing was done in a hurry at Quiquendone, the dramatic pieces had to be performed in harmony with the peculiar temperament of the Quiquendonians. Though the doors of the theatre were regularly thrown open at four o’clock and closed again at ten, it had never been known that more than two acts were played during the six intervening hours. “Robert le Diable,” “Les Huguenots,” or “Guillaume Tell” usually took up three evenings, so slow was the execution of these masterpieces. The vivaces, at the theatre of Quiquendone, lagged like real adagios. The allegros were “long-drawn out” indeed. The demisemiquavers were scarcely equal to the ordinary semibreves of other countries. The most rapid runs, performed according to Quiquendonian taste, had the solemn march of a chant. The gayest shakes were languishing and measured, that they might not shock the ears of the dilettanti. To give an example, the rapid air sung by Figaro, on his entrance in the first act of “Le Barbiér de Séville,” lasted fifty-eight minutes — when the actor was particularly enthusiastic.

Artists from abroad, as might be supposed, were forced to conform themselves to Quiquendonian fashions; but as they were well paid, they did not complain, and willingly obeyed the leader’s baton, which never beat more than eight measures to the minute in the allegros.

But what applause greeted these artists, who enchanted without ever wearying the audiences of Quiquendone! All hands clapped one after another at tolerably long intervals, which the papers characterized as “frantic applause;” and sometimes nothing but the lavish prodigality with which mortar and stone had been used in the twelfth century saved the roof of the hall from falling in.

Besides, the theatre had only one performance a week, that these enthusiastic Flemish folk might not be too much excited; and this enabled the actors to study their parts more thoroughly, and the spectators to digest more at leisure the beauties of the masterpieces brought out.

Such had long been the drama at Quiquendone. Foreign artists were in the habit of making engagements with the director of the town, when they wanted to rest after their exertions in other scenes; and it seemed as if nothing could ever change these inveterate customs, when, a fortnight after the Schut–Custos affair, an unlooked-for incident occurred to throw the population into fresh agitation.

It was on a Saturday, an opera day. It was not yet intended, as may well be supposed, to inaugurate the new illumination. No; the pipes had reached the hall, but, for reasons indicated above, the burners had not yet been placed, and the wax-candles still shed their soft light upon the numerous spectators who filled the theatre. The doors had been opened to the public at one o’clock, and by three the hall was half full. A queue had at one time been formed, which extended as far as the end of the Place Saint Ernuph, in front of the shop of Josse Lietrinck the apothecary. This eagerness was significant of an unusually attractive performance.

“Are you going to the theatre this evening?” inquired the counsellor the same morning of the burgomaster.

“I shall not fail to do so,” returned Van Tricasse, “and I shall take Madame Van Tricasse, as well as our daughter Suzel and our dear Tatanémance, who all dote on good music.”

“Mademoiselle Suzel is going then?”

“Certainly, Niklausse.”

“Then my son Frantz will be one of the first to arrive,” said Niklausse.

“A spirited boy, Niklausse,” replied the burgomaster sententiously; “but hot-headed! He will require watching!”

“He loves, Van Tricasse,— he loves your charming Suzel.”

“Well, Niklausse, he shall marry her. Now that we have agreed on this marriage, what more can he desire?”

“He desires nothing, Van Tricasse, the dear boy! But, in short — we’ll say no more about it — he will not be the last to get his ticket at the box-office.”

“Ah, vivacious and ardent youth!” replied the burgomaster, recalling his own past. “We have also been thus, my worthy counsellor! We have loved — we too! We have danced attendance in our day! Till to-night, then, till to-night! By-the-bye, do you know this Fiovaranti is a great artist? And what a welcome he has received among us! It will be long before he will forget the applause of Quiquendone!”

The tenor Fiovaranti was, indeed, going to sing; Fiovaranti, who, by his talents as a virtuoso, his perfect method, his melodious voice, provoked a real enthusiasm among the lovers of music in the town.

For three weeks Fiovaranti had been achieving a brilliant success in “Les Huguenots.” The first act, interpreted according to the taste of the Quiquendonians, had occupied an entire evening of the first week of the month.— Another evening in the second week, prolonged by infinite andantes, had elicited for the celebrated singer a real ovation. His success had been still more marked in the third act of Meyerbeer’s masterpiece. But now Fiovaranti was to appear in the fourth act, which was to be performed on this evening before an impatient public. Ah, the duet between Raoul and Valentine, that pathetic love-song for two voices, that strain so full of crescendos, stringendos, and piu crescendos — all this, sung slowly, compendiously, interminably! Ah, how delightful!

At four o’clock the hall was full. The boxes, the orchestra, the pit, were overflowing. In the front stalls sat the Burgomaster Van Tricasse, Mademoiselle Van Tricasse, Madame Van Tricasse, and the amiable Tatanémance in a green bonnet; not far off were the Counsellor Niklausse and his family, not forgetting the amorous Frantz. The families of Custos the doctor, of Schut the advocate, of Honoré Syntax the chief judge, of Norbet Sontman the insurance director, of the banker Collaert, gone mad on German music, and himself somewhat of an amateur, and the teacher Rupp, and the master of the academy, Jerome Resh, and the civil commissary, and so many other notabilities of the town that they could not be enumerated here without wearying the reader’s patience, were visible in different parts of the hall.

It was customary for the Quiquendonians, while awaiting the rise of the curtain, to sit silent, some reading the paper, others whispering low to each other, some making their way to their seats slowly and noiselessly, others casting timid looks towards the bewitching beauties in the galleries.

But on this evening a looker-on might have observed that, even before the curtain rose, there was unusual animation among the audience. People were restless who were never known to be restless before. The ladies’ fans fluttered with abnormal rapidity. All appeared to be inhaling air of exceptional stimulating power. Every one breathed more freely. The eyes of some became unwontedly bright, and seemed to give forth a light equal to that of the candles, which themselves certainly threw a more brilliant light over the hall. It was evident that people saw more clearly, though the number of candles had not been increased. Ah, if Doctor Ox’s experiment were being tried! But it was not being tried, as yet.

The musicians of the orchestra at last took their places. The first violin had gone to the stand to give a modest la to his colleagues. The stringed instruments, the wind instruments, the drums and cymbals, were in accord. The conductor only waited the sound of the bell to beat the first bar.

The bell sounds. The fourth act begins. The allegro appassionato of the inter-act is played as usual, with a majestic deliberation which would have made Meyerbeer frantic, and all the majesty of which was appreciated by the Quiquendonian dilettanti.

But soon the leader perceived that he was no longer master of his musicians. He found it difficult to restrain them, though usually so obedient and calm. The wind instruments betrayed a tendency to hasten the movements, and it was necessary to hold them back with a firm hand, for they would otherwise outstrip the stringed instruments; which, from a musical point of view, would have been disastrous. The bassoon himself, the son of Josse Lietrinck the apothecary, a well-bred young man, seemed to lose his self-control.

Meanwhile Valentine has begun her recitative, “I am alone,” &c.; but she hurries it.

The leader and all his musicians, perhaps unconsciously, follow her in her cantabile, which should be taken deliberately, like a 12/8 as it is. When Raoul appears at the door at the bottom of the stage, between the moment when Valentine goes to him and that when she conceals herself in the chamber at the side, a quarter of an hour does not elapse; while formerly, according to the traditions of the Quiquendone theatre, this recitative of thirty-seven bars was wont to last just thirty-seven minutes.

Saint Bris, Nevers, Cavannes, and the Catholic nobles have appeared, somewhat prematurely, perhaps, upon the scene. The composer has marked allergo pomposo on the score. The orchestra and the lords proceed allegro indeed, but not at all pomposo, and at the chorus, in the famous scene of the “benediction of the poniards,” they no longer keep to the enjoined allegro. Singers and musicians broke away impetuously. The leader does not even attempt to restrain them. Nor do the public protest; on the contrary, the people find themselves carried away, and see that they are involved in the movement, and that the movement responds to the impulses of their souls.

“Will you, with me, deliver the land,

From troubles increasing, an impious band?”

They promise, they swear. Nevers has scarcely time to protest, and to sing that “among his ancestors were many soldiers, but never an assassin.” He is arrested. The police and the aldermen rush forward and rapidly swear “to strike all at once.” Saint Bris shouts the recitative which summons the Catholics to vengeance. The three monks, with white scarfs, hasten in by the door at the back of Nevers’s room, without making any account of the stage directions, which enjoin on them to advance slowly. Already all the artists have drawn sword or poniard, which the three monks bless in a trice. The soprani tenors, bassos, attack the allegro furioso with cries of rage, and of a dramatic 6/8 time they make it 6/8 quadrille time. Then they rush out, bellowing,—

“At midnight,

Noiselessly,

God wills it,

Yes,

At midnight.”

At this moment the audience start to their feet. Everybody is agitated — in the boxes, the pit, the galleries. It seems as if the spectators are about to rush upon the stage, the Burgomaster Van Tricasse at their head, to join with the conspirators and annihilate the Huguenots, whose religious opinions, however, they share. They applaud, call before the curtain, make loud acclamations! Tatanémance grasps her bonnet with feverish hand. The candles throw out a lurid glow of light.

Raoul, instead of slowly raising the curtain, tears it apart with a superb gesture and finds himself confronting Valentine.

At last! It is the grand duet, and it starts off allegro vivace. Raoul does not wait for Valentine’s pleading, and Valentine does not wait for Raoul’s responses.

The fine passage beginning, “Danger is passing, time is flying,” becomes one of those rapid airs which have made Offenbach famous, when he composes a dance for conspirators. The andante amoroso, “Thou hast said it, aye, thou lovest me,” becomes a real vivace furioso, and the violoncello ceases to imitate the inflections of the singer’s voice, as indicated in the composer’s score. In vain Raoul cries, “Speak on, and prolong the ineffable slumber of my soul.” Valentine cannot “prolong.” It is evident that an unaccustomed fire devours her. Her b’s and her c’s above the stave were dreadfully shrill. He struggles, he gesticulates, he is all in a glow.

The alarum is heard; the bell resounds; but what a panting bell! The bell-ringer has evidently lost his self-control. It is a frightful tocsin, which violently struggles against the fury of the orchestra.

Finally the air which ends this magnificent act, beginning, “No more love, no more intoxication, O the remorse that oppresses me!” which the composer marks allegro con moto, becomes a wild prestissimo. You would say an express-train was whirling by. The alarum resounds again. Valentine falls fainting. Raoul precipitates himself from the window.

It was high time. The orchestra, really intoxicated, could not have gone on. The leader’s baton is no longer anything but a broken stick on the prompter’s box. The violin strings are broken, and their necks twisted. In his fury the drummer has burst his drum. The counter-bassist has perched on the top of his musical monster. The first clarionet has swallowed the reed of his instrument, and the second hautboy is chewing his reed keys. The groove of the trombone is strained, and finally the unhappy cornist cannot withdraw his hand from the bell of his horn, into which he had thrust it too far.

And the audience! The audience, panting, all in a heat, gesticulates and howls. All the faces are as red as if a fire were burning within their bodies. They crowd each other, hustle each other to get out — the men without hats, the women without mantles! They elbow each other in the corridors, crush between the doors, quarrel, fight! There are no longer any officials, any burgomaster. All are equal amid this infernal frenzy!

Some moments after, when all have reached the street, each one resumes his habitual tranquillity, and peaceably enters his house, with a confused remembrance of what he has just experienced.

The fourth act of the “Huguenots,” which formerly lasted six hours, began, on this evening at half-past four, and ended at twelve minutes before five.

It had only lasted eighteen minutes!

Chapter 8

In which the Ancient and Solemn German Waltz Becomes a Whirlwind.

But if the spectators, on leaving the theatre, resumed their customary calm, if they quietly regained their homes, preserving only a sort of passing stupefaction, they had none the less undergone a remarkable exaltation, and overcome and weary as if they had committed some excess of dissipation, they fell heavily upon their beds.

The next day each Quiquendonian had a kind of recollection of what had occurred the evening before. One missed his hat, lost in the hubbub; another a coat-flap, torn in the brawl; one her delicately fashioned shoe, another her best mantle. Memory returned to these worthy people, and with it a certain shame for their unjustifiable agitation. It seemed to them an orgy in which they were the unconscious heroes and heroines. They did not speak of it; they did not wish to think of it. But the most astounded personage in the town was Van Tricasse the burgomaster.

The next morning, on waking, he could not find his wig. Lotchè looked everywhere for it, but in vain. The wig had remained on the field of battle. As for having it publicly claimed by Jean Mistrol, the town-crier,— no, it would not do. It were better to lose the wig than to advertise himself thus, as he had the honour to be the first magistrate of Quiquendone.

The worthy Van Tricasse was reflecting upon this, extended beneath his sheets, with bruised body, heavy head, furred tongue, and burning breast. He felt no desire to get up; on the contrary; and his brain worked more during this morning than it had probably worked before for forty years. The worthy magistrate recalled to his mind all the incidents of the incomprehensible performance. He connected them with the events which had taken place shortly before at Doctor Ox’s reception. He tried to discover the causes of the singular excitability which, on two occasions, had betrayed itself in the best citizens of the town.

“What can be going on?” he asked himself. “What giddy spirit has taken possession of my peaceable town of Quiquendone? Are we about to go mad, and must we make the town one vast asylum? For yesterday we were all there, notables, counsellors, judges, advocates, physicians, schoolmasters; and ail, if my memory serves me,— all of us were assailed by this excess of furious folly! But what was there in that infernal music? It is inexplicable! Yet I certainly ate or drank nothing which could put me into such a state. No; yesterday I had for dinner a slice of overdone veal, several spoonfuls of spinach with sugar, eggs, and a little beer and water,— that couldn’t get into my head! No! There is something that I cannot explain, and as, after all, I am responsible for the conduct of the citizens, I will have an investigation.”

But the investigation, though decided upon by the municipal council, produced no result. If the facts were clear, the causes escaped the sagacity of the magistrates. Besides, tranquillity had been restored in the public mind, and with tranquillity, forgetfulness of the strange scenes of the theatre. The newspapers avoided speaking of them, and the account of the performance which appeared in the “Quiquendone Memorial,” made no allusion to this intoxication of the entire audience.

Meanwhile, though the town resumed its habitual phlegm, and became apparently Flemish as before, it was observable that, at bottom, the character and temperament of the people changed little by little. One might have truly said, with Dominique Custos, the doctor, that “their nerves were affected.”

Let us explain. This undoubted change only took place under certain conditions. When the Quiquendonians passed through the streets of the town, walked in the squares or along the Vaar, they were always the cold and methodical people of former days. So, too, when they remained at home, some working with their hands and others with their heads,— these doing nothing, those thinking nothing,— their private life was silent, inert, vegetating as before. No quarrels, no household squabbles, no acceleration in the beating of the heart, no excitement of the brain. The mean of their pulsations remained as it was of old, from fifty to fifty-two per minute.

But, strange and inexplicable phenomenon though it was, which would have defied the sagacity of the most ingenious physiologists of the day, if the inhabitants of Quiquendone did not change in their home life, they were visibly changed in their civil life and in their relations between man and man, to which it leads.

If they met together in some public edifice, it did not “work well,” as Commissary Passauf expressed it. On ‘change, at the town-hall, in the amphitheatre of the academy, at the sessions of the council, as well as at the reunions of the savants, a strange excitement seized the assembled citizens. Their relations with each other became embarrassing before they had been together an hour. In two hours the discussion degenerated into an angry dispute. Heads became heated, and personalities were used. Even at church, during the sermon, the faithful could not listen to Van Stabel, the minister, in patience, and he threw himself about in the pulpit and lectured his flock with far more than his usual severity. At last this state of things brought about altercations more grave, alas! than that between Gustos and Schut, and if they did not require the interference of the authorities, it was because the antagonists, after returning home, found there, with its calm, forgetfulness of the offences offered and received.

This peculiarity could not be observed by these minds, which were absolutely incapable of recognizing what was passing in them. One person only in the town, he whose office the council had thought of suppressing for thirty years, Michael Passauf, had remarked that this excitement, which was absent from private houses, quickly revealed itself in public edifices; and he asked himself, not without a certain anxiety, what would happen if this infection should ever develop itself in the family mansions, and if the epidemic — this was the word he used — should extend through the streets of the town. Then there would be no more forgetfulness of insults, no more tranquillity, no intermission in the delirium; but a permanent inflammation, which would inevitably bring the Quiquendonians into collision with each other.

“What would happen then?” Commissary Passauf asked himself in terror. “How could these furious savages be arrested? How check these goaded temperaments? My office would be no longer a sinecure, and the council would be obliged to double my salary — unless it should arrest me myself, for disturbing the public peace!”

These very reasonable fears began to be realized. The infection spread from ‘change, the theatre, the church, the town-hall, the academy, the market, into private houses, and that in less than a fortnight after the terrible performance of the “Huguenots.”

Its first symptoms appeared in the house of Collaert, the banker.

That wealthy personage gave a ball, or at least a dancing-party, to the notabilities of the town. He had issued, some months before, a loan of thirty thousand francs, three quarters of which had been subscribed; and to celebrate this financial success, he had opened his drawing-rooms, and given a party to his fellow-citizens.

Everybody knows that Flemish parties are innocent and tranquil enough, the principal expense of which is usually in beer and syrups. Some conversation on the weather, the appearance of the crops, the fine condition of the gardens, the care of flowers, and especially of tulips; a slow and measured dance, from time to time, perhaps a minuet; sometimes a waltz, but one of those German waltzes which achieve a turn and a half per minute, and during which the dancers hold each other as far apart as their arms will permit,— such is the usual fashion of the balls attended by the aristocratic society of Quiquendone. The polka, after being altered to four time, had tried to become accustomed to it; but the dancers always lagged behind the orchestra, no matter how slow the measure, and it had to be abandoned.

These peaceable reunions, in which the youths and maidens enjoyed an honest and moderate pleasure, had never been attended by any outburst of ill-nature. Why, then, on this evening at Collaert the banker’s, did the syrups seem to be transformed into heady wines, into sparkling champagne, into heating punches? Why, towards the middle of the evening, did a sort of mysterious intoxication take possession of the guests? Why did the minuet become a jig? Why did the orchestra hurry with its harmonies? Why did the candles, just as at the theatre, burn with unwonted refulgence? What electric current invaded the banker’s drawing-rooms? How happened it that the couples held each other so closely, and clasped each other’s hands so convulsively, that the “cavaliers seuls” made themselves conspicuous by certain extraordinary steps in that figure usually so grave, so solemn, so majestic, so very proper?

Alas! what OEdipus could have answered these unsolvable questions? Commissary Passauf, who was present at the party, saw the storm coming distinctly, but he could not control it or fly from it, and he felt a kind of intoxication entering his own brain. All his physical and emotional faculties increased in intensity. He was seen, several times, to throw himself upon the confectionery and devour the dishes, as if he had just broken a long fast.

The animation of the ball was increasing all this while. A long murmur, like a dull buzzing, escaped from all breasts. They danced — really danced. The feet were agitated by increasing frenzy. The faces became as purple as those of Silenus. The eyes shone like carbuncles. The general fermentation rose to the highest pitch.

And when the orchestra thundered out the waltz in “Der Freyschütz,”— when this waltz, so German, and with a movement so slow, was attacked with wild arms by the musicians,— ah! it was no longer a waltz, but an insensate whirlwind, a giddy rotation, a gyration worthy of being led by some Mephistopheles, beating the measure with a firebrand! Then a galop, an infernal galop, which lasted an hour without any one being able to stop it, whirled off, in its windings, across the halls, the drawing-rooms, the antechambers, by the staircases, from the cellar to the garret of the opulent mansion, the young men and young girls, the fathers and mothers, people of every age, of every weight, of both sexes; Collaert, the fat banker, and Madame Collaert, and the counsellors, and the magistrates, and the chief justice, and Niklausse, and Madame Van Tricasse, and the Burgomaster Van Tricasse, and the Commissary Passauf himself, who never could recall afterwards who had been his partner on that terrible evening.

But she did not forget! And ever since that day she has seen in her dreams the fiery commissary, enfolding her in an impassioned embrace! And “she”— was the amiable Tatanémance!

Chapter 9

In which Doctor Ox and Ygène, His Assistant, Say a Few Words.

“Well, Ygène?”

“Well, master, all is ready. The laying of the pipes is finished.”

“At last! Now, then, we are going to operate on a large scale, on the masses!”

Chapter 10

In which it Will Be Seen that the Epidemic Invades the Entire Town, and what Effect it Produces.

During the following months the evil, in place of subsiding, became more extended. From private houses the epidemic spread into the streets. The town of Quiquendone was no longer to be recognized.

A phenomenon yet stranger than those which had already happened, now appeared; not only the animal kingdom, but the vegetable kingdom itself, became subject to the mysterious influence.

According to the ordinary course of things, epidemics are special in their operation. Those which attack humanity spare the animals, and those which attack the animals spare the vegetables. A horse was never inflicted with smallpox, nor a man with the cattle-plague, nor do sheep suffer from the potato-rot. But here all the laws of nature seemed to be overturned. Not only were the character, temperament, and ideas of the townsfolk changed, but the domestic animals — dogs and cats, horses and cows, asses and goats — suffered from this epidemic influence, as if their habitual equilibrium had been changed. The plants themselves were infected by a similar strange metamorphosis.

In the gardens and vegetable patches and orchards very curious symptoms manifested themselves. Climbing plants climbed more audaciously. Tufted plants became more tufted than ever. Shrubs became trees. Cereals, scarcely sown, showed their little green heads, and gained, in the same length of time, as much in inches as formerly, under the most favourable circumstances, they had gained in fractions. Asparagus attained the height of several feet; the artichokes swelled to the size of melons, the melons to the size of pumpkins, the pumpkins to the size of gourds, the gourds to the size of the belfry bell, which measured, in truth, nine feet in diameter. The cabbages were bushes, and the mushrooms umbrellas.

The fruits did not lag behind the vegetables. It required two persons to eat a strawberry, and four to consume a pear. The grapes also attained the enormous proportions of those so well depicted by Poussin in his “Return of the Envoys to the Promised Land.”

It was the same with the flowers: immense violets spread the most penetrating perfumes through the air; exaggerated roses shone with the brightest colours; lilies formed, in a few days, impenetrable copses; geraniums, daisies, camelias, rhododendrons, invaded the garden walks, and stifled each other. And the tulips,— those dear liliaceous plants so dear to the Flemish heart, what emotion they must have caused to their zealous cultivators! The worthy Van Bistrom nearly fell over backwards, one day, on seeing in his garden an enormous “Tulipa gesneriana,” a gigantic monster, whose cup afforded space to a nest for a whole family of robins!

The entire town flocked to see this floral phenomenon, and renamed it the “Tulipa quiquendonia”.

But alas! if these plants, these fruits, these flowers, grew visibly to the naked eye, if all the vegetables insisted on assuming colossal proportions, if the brilliancy of their colours and perfume intoxicated the smell and the sight, they quickly withered. The air which they absorbed rapidly exhausted them, and they soon died, faded, and dried up.

Such was the fate of the famous tulip, which, after several days of splendour, became emaciated, and fell lifeless.

It was soon the same with the domestic animals, from the house-dog to the stable pig, from the canary in its cage to the turkey of the back-court. It must be said that in ordinary times these animals were not less phlegmatic than their masters. The dogs and cats vegetated rather than lived. They never betrayed a wag of pleasure nor a snarl of wrath. Their tails moved no more than if they had been made of bronze. Such a thing as a bite or scratch from any of them had not been known from time immemorial. As for mad dogs, they were looked upon as imaginary beasts, like the griffins and the rest in the menagerie of the apocalypse.