| Library / Literary Works |

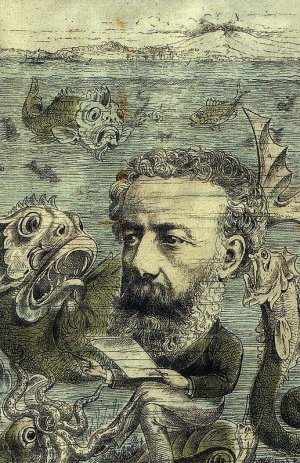

Jules Verne

The Field of Ice

Part II of The Adventures of Captain Hatteras

Table of Contents

1. The Doctor’s Inventory

2. First Words of Altamont

3. A Seventeen Days’ March

4. The Last Charge of Powder

5. The Seal and the Bear

6. The Porpoise

7. An Important Discussion.

8. An Excursion to the North of Victoria Bay

9. Cold and Heat

10. Winter Pleasures

11. Traces of Bears

12. Imprisoned in Doctor’s House

13. The Mine.

14. An Arctic Spring.

15. The North-West Passage.

16. Arctic Arcadia

17. Altamont’s Revenge

18. Final Preparations

19. March to the North

20. Footprints in the Snow

21. The Open Sea.

22. Getting Near the Pole

23. The English Flag

24. Mount Hatteras

25. Return South.

26. Conclusion.

Chapter 1. The Doctor’s Inventory

It was a bold project of Hatteras to push his way to the North Pole, and gain for his country the honour and glory of its discovery. But he had done all that lay in human power now, and, after having struggled for nine months against currents and tempests, shattering icebergs and breaking through almost insurmountable barriers, amid the cold of an unprecedented winter, after having outdistanced all his predecessors and accomplished half his task, he suddenly saw all his hopes blasted. The treachery, or rather the despondency, of his worn-out crew, and the criminal folly of one or two leading spirits among them had left him and his little band of men in a terrible situation — helpless in an icy desert, two thousand five hundred miles away from their native land, and without even a ship to shelter them.

However, the courage of Hatteras was still undaunted. The three men which were left him were the best on board his brig, and while they remained he might venture to hope.

After the cheerful, manly words of the captain, the Doctor felt the best thing to be done was to look their prospects fairly in the face, and know the exact state of things. Accordingly, leaving his companions, he stole away alone down to the scene of the explosion.

Of the Forward, the brig that had been so carefully built and had become so dear, not a vestige remained. Shapeless blackened fragments, twisted bars of iron, cable ends still smouldering, and here and there in the distance spiral wreaths of smoke, met his eye on all sides. His cabin and all his precious treasures were gone, his books, and instruments, and collections reduced to ashes. As he stood thinking mournfully of his irreparable loss, he was joined by Johnson, who grasped his offered hand in speechless sorrow.

“What’s to become of us?” asked the Doctor.

“Who can tell!” was the old sailor’s reply.

“Anyhow,” said Clawbonny, “do not let us despair! Let us be men!”

“Yes, Mr. Clawbonny, you are right. Now is the time to show our mettle. We are in a bad plight, and how to get out of it, that is the question.”

“Poor old brig!” exclaimed the Doctor. “I had grown so attached to her. I loved her as one loves a house where he has spent a life-time.”

“Ay! it’s strange what a hold those planks and beams get on a fellow’s heart.”

“And the long-boat — is that burnt?” asked the Doctor.

“No, Mr. Clawbonny. Shandon and his gang have carried it off.”

“And the pirogue?”

“Shivered into a thousand pieces? Stop. Do you see those bits of sheet-iron? That is all that remains of it.”

“Then we have nothing but the Halkett-boat?”

“Yes, we have that still, thanks to your idea of taking it with you.”

“That isn’t much,” said the Doctor.

“Oh, those base traitors!” exclaimed Johnson. “Heaven punish them as they deserve!”

“Johnson,” returned the Doctor, gently, “we must not forget how sorely they have been tried. Only the best remain good in the evil day; few can stand trouble. Let us pity our fellow-sufferers, and not curse them.”

For the next few minutes both were silent, and then Johnson asked what had become of the sledge.

“We left it about a mile off,” was the reply.

“In charge of Simpson?”

“No, Simpson is dead, poor fellow!”

“Simpson dead!”

“Yes, his strength gave way entirely, and he first sank.”

“Poor Simpson! And yet who knows if he isn’t rather to be envied?”

“But, for the dead man we have left behind, we have brought back a dying one.”

“A dying man?”

“Yes, Captain Altamont.”

And in a few words he informed Johnson of their discovery.

“An American!” said Johnson, as the recital was ended.

“Yes, everything goes to prove that. But I wonder what the Porpoise was, and what brought her in these seas?”

“She rushed on to her ruin like the rest of foolhardy adventurers; but, tell me, did you find the coal?”

The Doctor shook his head sadly.

“No coal! not a vestige! No, we did not even get as far as the place mentioned by Sir Edward Belcher.”

“Then we have no fuel whatever?” said the old sailor.

“No.”

“And no provisions?”

“No.”

“And no ship to make our way back to England?”

It required courage indeed to face these gloomy realities, but, after a moment’s silence, Johnson said again —

“Well, at any rate we know exactly how we stand. The first thing to be done now is to make a hut, for we can’t stay long exposed to this temperature.”

“Yes, we’ll soon manage that with Bell’s help,” replied the Doctor. “Then we must go and find the sledge, and bring back the American, and have a consultation with Hatteras.”

“Poor captain,” said Johnson, always forgetting his own troubles, “how he must feel it!”

Clawbonny and Bell found Hatteras standing motionless, his arms folded in his usual fashion. He seemed gazing into space, but his face had recovered its calm, self-possessed expression. His faithful dog stood beside him, like his master, apparently insensible to the biting cold, though the temperature was 32 degrees below zero.

Bell lay on the ice in an almost inanimate condition. Johnson had to take vigorous measures to rouse him, but at last, by dint of shaking and rubbing him with snow, he succeeded.

“Come, Bell,” he cried, “don’t give way like this. Exert yourself, my man; we must have a talk about our situation, and we need a place to put our heads in. Come and help me, Bell. You haven’t forgotten how to make a snow hut, have you? There is an iceberg all ready to hand; we’ve only got to hollow it out. Let’s set to work; we shall find that is the best remedy for us.”

Bell tried to shake off his torpor and help his comrade, while Mr. Clawbonny undertook to go and fetch the sledge and the dogs.

“Will you go with him, captain?” asked Johnson.

“No, my friend,” said Hatteras, in a gentle tone, “if the Doctor will kindly undertake the task. Before the day ends I must come to some resolution, and I need to be alone to think. Go. Do meantime whatever you think best. I will deal with the future.”

Johnson went back to the Doctor, and said —

“It’s very strange, but the captain seems quite to have got over his anger. I never heard him speak so gently before.”

“So much the better,” said Clawbonny. “Believe me, Johnson, that man can save us yet.”

And drawing his hood as closely round his head as possible, the Doctor seized his iron-tipped staff, and set out without further delay.

Johnson and Bell commenced operations immediately. They had simply to dig a hole in the heart of a great block of ice; but it was not easy work, owing to the extreme hardness of the material. However, this very hardness guaranteed the solidity of the dwelling, and the further their labours advanced the more they became sheltered.

Hatteras alternately paced up and down, and stood motionless, evidently shrinking from any approach to the scene of explosion.

In about an hour the Doctor returned, bringing with him Altamont lying on the sledge, wrapped up in the folds of the tent. The poor dogs were so exhausted from starvation that they could scarcely draw it along, and they had begun to gnaw their harness. It was, indeed, high time for feasts and men to take food and rest.

While the hut was being still further dug out, the Doctor went foraging about, and had the good fortune to find a little stove, almost undamaged by the explosion. He soon restored it to working trim, and, by the time the hut was completed, had filled it with wood and got it lighted. Before long it was roaring, and diffusing a genial warmth on all sides. The American was brought in and laid on blankets, and the four Englishmen seated themselves round the fire to enjoy their scanty meal of biscuit and hot tea, the last remains of the provisions on the sledge. Not a word was spoken by Hatteras, and the others respected his silence.

When the meal was over, the Doctor rose and went out, making a sign to Johnson to follow.

“Come, Johnson,” he said, “we will take an inventory of all we have left. We must know exactly how we are off, and our treasures are scattered in all directions; so we had better begin, and pick them up as fast as possible, for the snow may fall at any moment, and then it would be quite useless to look for anything.”

“Don’t let us lose a minute, then,” replied Johnson. “Fire and food — those are our chief wants.”

“Very well, you take one side and I’ll take the other, and we’ll search from the centre to the circumference.”

This task occupied two hours, and all they discovered was a little salt meat, about 50 lbs. of pemmican, three sacks of biscuits, a small stock of chocolate, five or six pints of brandy, and about 2 lbs. of coffee, picked up bean by bean off the ice.

Neither blankets, nor hammocks, nor clothing — all had been consumed in the devouring flame.

This slender store of provisions would hardly last three weeks, and they had wood enough to supply the stove for about the same time.

Now that the inventory was made, the next business was to fetch the sledge. The tired-out dogs were harnessed sorely against their will, and before long returned bringing the few but precious treasures found among the débris of the brig. These were safely deposited in the hut, and then Johnson and Clawbonny, half-frozen with their work, resumed their places beside their companions in misfortune.

Chapter 2. First Words of Altamont

About eight o’clock in the evening, the grey snow clouds cleared away for a little, and the stars shone out brilliantly in the sky.

Hatteras seized the opportunity and went out silently to take the altitude of some of the principal constellations. He wished to ascertain if the ice-field was still drifting.

In half an hour he returned and sat down in a corner of the hut, where he remained without stirring all night, motionless as if asleep, but in reality buried in deepest thought.

The next day the snow fell heavily, and the Doctor congratulated himself on his wise forethought, when he saw the white sheet lying three feet thick over the scene of the explosion, completely obliterating all traces of the Forward.

It was impossible to venture outside in such weather, but the stove drew capitally, and made the hut quite comfortable, or at any rate it seemed so to the weary, worn out adventurers.

The American was in less pain, and was evidently gradually coming back to life. He opened his eyes, but could not yet speak, for his lips were so affected by the scurvy that articulation was impossible, but he could hear and understand all that was said to him. On learning what had passed, and the circumstances of his discovery, he expressed his thanks by gestures, and the Doctor was too wise to let him know how brief his respite from death would prove. In three weeks at most every vestige of food would be gone.

About noon Hatteras roused himself, and going up to his friends, said —

“We must make up our minds what to do, but I must request Johnson to tell me first all the particulars of the mutiny on the brig, and how this final act of baseness came about.”

“What good will that do?” said the Doctor. “The fact is certain, and it is no use thinking over it.”

“I differ from your opinion,” rejoined Hatteras. “Let me hear the whole affair from Johnson, and then I will banish it from my thoughts.”

“Well,” said the boatswain, “this was how it happened. I did all in my power to prevent, but ——”

“I am sure of that, Johnson; and what’s more, I have no doubt the ringleaders had been hatching their plans for some time.”

“That’s my belief too,” said the Doctor.

“And so it is mine,” resumed Johnson; “for almost immediately after your departure Shandon, supported by the others, took the command of the ship.

I could not resist him, and from that moment everybody did pretty much as they pleased. Shandon made no attempt to restrain them: it was his policy to make them believe that their privations and toils were at an end. Economy was entirely disregarded. A blazing fire was kept up in the stove, and the men were allowed to eat and drink at discretion; not only tea and coffee was at their disposal, but all the spirits on board, and on men who had been so long deprived of ardent liquors, you may guess the result. They went on in this manner from the 7th to the 15th of January.”

“And this was Shandon’s doing?” asked Hatteras.

“Yes, captain.”

“Never mention his name to me again! Go on, Johnson.”

“It was about the 24th or 25th of January, that they resolved to abandon the ship. Their plan was to reach the west coast of Baffin’s Bay, and from thence to embark in the boat and follow the track of the whalers, or to get to some of the Greenland settlements on the eastern side. Provisions were abundant, and the sick men were so excited by the hope of return that they were almost well. They began their preparations for departure by making a sledge which they were to draw themselves, as they had no dogs. This was not ready till the 15th of February, and I was always hoping for your arrival, though I half dreaded it too, for you could have done nothing with the men, and they would have massacred you rather than remain on board. I tried my influence on each one separately, remonstrating and reasoning with them, and pointing out the dangers they would encounter, and also the cowardice of leaving you, but it was a mere waste of words; not even the best among them would listen to me. Shandon was impatient to be off, and fixed the 22nd of February for starting. The sledge and the boat were packed as closely as possible with provisions and spirits, and heaps of wood, to obtain which they had hewed the brig down to her water-line. The last day the men ran riot. They completely sacked the ship, and in a drunken paroxysm Pen and two or three others set it on fire. I fought and struggled against them, but they threw me down and assailed me with blows, and then the wretches, headed by Shandon, went off towards the east and were soon out of sight. I found myself alone on the burning ship, and what could I do? The fire- hole was completely blocked up with ice. I had not a single drop of water! For two days the Forward struggled with the flames, and you know the rest.”

A long silence followed the gloomy recital, broken at length by Hatteras, who said —

“Johnson, I thank you; you did all you could to save my ship, but single-handed you could not resist. Again I thank you, and now let the subject be dropped. Let us unite efforts for our common salvation. There are four of us, four companions, four friends, and all our lives are equally precious. Let each give his opinion on the best course for us to pursue.”

“You ask us then, Hatteras,” said the Doctor, “we are all devoted to you, and our words come from our hearts. But will you not state you own views first?”

“That would be little use,” said Hatteras, sadly; “my opinion might appear interested; let me hear all yours first.”

“Captain,” said Johnson, “before pronouncing on such an important matter, I wish to ask you a question.”

“Ask it, then, Johnson.”

“You went out yesterday to ascertain our exact position; well, is the field drifting or stationary?”

“Perfectly stationary. It had not moved since the last reckoning was made. I find we are just where we were before we left, in 80° 15” lat. and 97° 35” long.”

“And what distance are we from the nearest sea to the west?”

“About six hundred miles.”

“And that sea is ——?”

“Smith’s Sound,” was the reply.

“The same that we could not get through last April?”

“The same.”

“Well, captain, now we know our actual situation, we are in a better position to determine our course of action.”

“Speak your minds, then,” said Hatteras, again burying his head in his hands.

“What do you say, Bell?” asked the Doctor.

“It strikes me the case doesn’t need long thinking over,” said the carpenter. “We must get back at once without losing a single day or even a single hour, either to the south or west, and make our way to the nearest coast, even if we are two months doing it!”

“We have only food for three weeks,” replied Hatteras, without raising his head.

“Very well,” said Johnson, “we must make the journey in three weeks, since it is our last chance. Even if we can only crawl on our knees before we get to our destination, we must be there in twenty-five days.”

“This part of the Arctic Continent is unexplored. We may have to encounter difficulties. Mountains and glaciers may bar our progress,” objected Hatteras.

“I don’t see that’s any sufficient reason for not attempting it. We shall have to endure sufferings, no doubt, and perhaps many. We shall have to limit ourselves to the barest quantities of food, unless our guns should procure us anything.”

“There is only about half a pound of powder left,” said Hatteras.

“Come now, Hatteras, I know the full weight of your objections, and I am not deluding myself with vain hopes. But I think I can read your motive. Have you any practical suggestion to offer?”

“No,” said Hatteras, after a little hesitation.

“You don’t doubt our courage,” continued the Doctor. “We would follow you to the last — you know that. But must we not, meantime, give up all hope of reaching the Pole? Your plans have been defeated by treachery. Natural difficulties you might have overcome, but you have been outmatched by perfidy and human weakness. You have done all that man could do, and you would have succeeded I am certain; but situated as we are now, are you not obliged to relinquish your projects for the present, and is not a return to England even positively necessary before you could continue them?”

“Well, captain?” asked Johnson after waiting a considerable time for Hatteras to reply.

Thus interrogated, he raised his head, and said in a constrained tone —

“You think yourselves quite certain then of reaching the Sound, exhausted though you are, and almost without food?”

“No,” replied the Doctor, “but there is one thing certain, the Sound won’t come to us, we must go to it. We may chance to find some Esquimaux tribes further south.”

“Besides, isn’t there the chance of falling in with some ship that is wintering here?” asked Johnson.

“Even supposing the Sound is blocked up, couldn’t we get across to some Greenland or Danish settlement? At any rate, Hatteras, we can get nothing by remaining here. The route to England is towards the south, not the north.”

“Yes,” said Bell, “Mr. Clawbonny is right. We must start, and start at once. We have been forgetting our country too long already.”

“Is this your advice, Johnson?” asked Hatteras again.

“Yes, captain.”

“And yours, Doctor?”

“Yes, Hatteras.”

Hatteras remained silent, but his face, in spite of himself, betrayed his inward agitation. The issue of his whole life hung on the decision he had to make, for he felt that to return to England was to lose all! He could not venture on a fourth expedition.

The Doctor finding he did not reply, added —

“I ought also to have said, that there is not a moment to lose. The sledge must be loaded with the provisions at once, and as much wood as possible. I must confess six hundred miles is a long journey, but we can, or rather we must make twenty miles a day, which will bring us to the coast about the 26th of March.”

“But cannot we wait a few days yet?” said Hatteras.

“What are you hoping for?” asked Johnson.

“I don’t know. Who can tell the future? It is necessary, too, that you should get your strength a little recruited. You might sink down on the road with fatigue, without even a snow hut to shelter you.”

“But think of the terrible death that awaits us here,” replied the carpenter.

“My friends,” said Hatteras, in almost supplicating tones; “you are despairing too soon. I should propose that we should seek our deliverance towards the north, but you would refuse to follow me, and yet why should there not be Esquimaux tribes round about the Pole as well as towards the south? The open sea, of the existence of which we are certified, must wash the shores of continents. Nature is logical in all her doings. Consequently vegetation must be found there when the earth is no longer ice-bound. Is there not a promised land awaiting us in the north from which you would flee?”

Hatteras became animated as he spoke, and Doctor Clawbonny’s excitable nature was so wrought upon that his decision began to waver. He was on the point of yielding, when Johnson, with his wiser head and calmer temperament, recalled him to reason and duty by calling out —

“Come, Bell, let us be off to the sledge.”

“All right,” said Bell, and the two had risen to leave the hut, when Hatteras exclaimed —

“Oh, Johnson! You! you! Well, go! I shall stay, I shall stay!”

“Captain!” said Johnson, stopping in spite of himself.

“I shall stay, I tell you. Go! Leave me like the rest! Come, Duk, you and I will stay together.”

The faithful dog barked as if he understood, and settled himself down beside his master. Johnson looked at the Doctor, who seemed at a loss to know what to do, but came to the conclusion at last that the best way, meantime, was to calm Hatteras, even at the sacrifice of a day. He was just about to try the force of his eloquence in this direction, when he felt a light touch on his arm, and turning round saw Altamont who had crawled out of bed and managed to get on his knees. He was trying to speak, but his swollen lips could scarcely make a sound. Hatteras went towards him, and watched his efforts to articulate so attentively that in a few minutes he made out a word that sounded like Porpoise, and stooping over him he asked —

“Is it the Porpoise?”

Altamont made a sign in the affirmative, and Hatteras went on with his queries, now that he had found a clue.

“In these seas?”

The affirmative gesture was repeated.

“Is she in the north?”

“Yes.”

“Do you know her position?”

“Yes.”

“Exactly?”

“Yes.”

For a minute or so, nothing more was said, and the onlookers waited with palpitating hearts.

Then Hatteras spoke again and said —

“Listen to me. We must know the exact position of your vessel. I will count the degrees aloud, and you; will stop me when I come to the right one.”

The American assented by a motion of the head, and Hatteras began —

“We’ll take the longitude first. 105°, No? 106°, 107°? It is to the west, I suppose?”

“Yes,” replied Altamont.

“Let us go on, then: 109°, 110°, 112°, 114°, 116°, 118°, 120°.”

“Yes,” interrupted the sick man. “120° of longitude, and how many minutes? I will count.”

Hatteras began at number one, and when he got to fifteen, Altamont made a sign to stop.

“Very good,” said Hatteras; “now for the latitude. Are you listening? 80°, 81°, 82°, 83°.”

Again the sign to stop was made.

“Now for the minutes: 5’, 10’, 15’, 20’, 25’, 30’, 35’.”

Altamont stopped him once more, and smiled feebly.

“You say, then, that the Porpoise is in longitude 120° 15’, and latitude 83° 35’?”

“Yes,” sighed the American, and fell back motionless in the Doctor’s arms, completely overpowered by the effort he had made.

“Friends!” exclaimed Hatteras; “you see I was right. Our salvation lies indeed in the north, always in the north. We shall be saved!”

But the joyous, exulting words had hardly escaped his lips before a sudden thought made his countenance change. The serpent of jealousy had stung him, for this stranger was an American, and he had reached three degrees nearer the Pole than the ill-fated Forward.

Chapter 3. A Seventeen Days’ March

These first words of Altamont had completely changed the whole aspect of affairs, but his communication was still incomplete, and, after giving him a little time to rest, the Doctor undertook the task of conversing again with him, putting his questions in such a form that a movement of the head or eyes would be a sufficient answer.

He soon ascertained that the Porpoise was a three-mast American ship, from New York, wrecked on the ice, with provisions and combustibles in abundance still on board, and that, though she had been thrown on her side, she had not gone to pieces, and there was every chance of saving her cargo.

Altamont and his crew had left her two months previously, taking the long boat with them on a sledge. They intended to get to Smith’s Sound, and reach some whaler that would take them back to America; but one after another succumbed to fatigue and illness, till at last Altamont and two men were all that remained out of thirty; and truly he had survived by a providential miracle, while his two companions already lay beside him in the sleep of death.

Hatteras wished to know why the Porpoise had come so far north, and learned in reply that she had been irresistibly driven there by the ice. But his anxious fears were not satisfied with this explanation, and he asked further what was the purpose of his voyage. Altamont said he wanted to make the north-west passage, and this appeared to content the jealous Englishman, for he made no more reference to the subject. “Well,” said the Doctor, “it strikes me that, instead of trying to get to Baffin’s Bay, our best plan would be to go in search of the Porpoise, for here lies a ship a full third of the distance nearer, and, more than that, stocked with everything necessary for winter quarters.”

“I see no other course open to us,” replied Bell.

“And the sooner we go the better,” added Johnson, “for the time we allow ourselves must depend on our provisions.”

“You are right, Johnson,” returned the Doctor. “If we start to- morrow, we must reach the Porpoise by the 15th of March, unless we mean to die of starvation. What do you say, Hatteras?”

“Let us make preparations immediately, but perhaps the route may be longer than we suppose.”

“How can that be, captain? The man seems quite sure of the position of his ship,” said the Doctor.

“But suppose the ice-field should have drifted like ours?”

Here Altamont, who was listening attentively, made a sign that he wished to speak, and, after much difficulty, he succeeded in telling the Doctor that the Porpoise had struck on rocks near the coast, and that it was impossible for her to move.

This was re-assuring information, though it cut off all hope of returning to Europe, unless Bell could construct a smaller ship out of the wreck.

No time was lost in getting ready to start. The sledge was the principal thing, as it needed thorough repair. There was plenty of wood, and, profiting by the experience they had recently had of this mode of transit, several improvements were made by Bell.

Inside, a sort of couch was laid for the American, and covered over with the tent. The small stock of provisions did not add much to the weight, but, to make up the deficiency, as much wood was piled up on it as it could hold.

The Doctor did the packing, and made an exact calculation of how long their stores would last. He found that, by allowing three-quarter rations to each man and full rations to the dogs, they might hold out for three weeks.

Towards seven in the evening, they felt so worn out that they were obliged to give up work for the night; but, before lying down to sleep, they heaped up the wood in the stove, and made a roaring fire, determined to allow themselves this parting luxury. As they gathered round it, basking in the unaccustomed heat, and enjoying their hot coffee and biscuits and pemmican, they became quite cheerful, and forgot all their sufferings.

About seven in the morning they set to work again and by three in the afternoon everything was ready.

It was almost dark, for, though the sun had reappeared above the horizon since the 31st of January, his light was feeble and of short duration. Happily the moon would rise about half-past six, and her soft beams would give sufficient light to show the road.

The parting moment came. Altamont was overjoyed at the idea of starting, though the jolting would necessarily increase his sufferings, for the Doctor would find on board the medicines he required for his cure.

They lifted him on to the sledge, and laid him as comfortably as possible, and then harnessed the dogs, including Duk. One final look towards the icy bed where the Forward had been, and the little party set out for the Porpoise. Bell was scout, as before; the Doctor and Johnson took each a side of the sledge, and lent a helping hand when necessary; while Hatteras walked behind to keep all in the right track.

They got on pretty quickly, for the weather was good, and the ice smooth and hard, allowing the sledge to glide easily along, yet the temperature was so low that men and dogs were soon panting, and had often to stop and take breath. About seven the moon shone out, and irradiated the whole horizon. Far as the eye could see, there was nothing visible but a wide- stretching level plain of ice, without a solitary hummock or patch to relieve the uniformity.

As the Doctor remarked to his companion, it looked like some vast, monotonous desert.

“Ay! Mr. Clawbonny, it is a desert, but we shan’t die of thirst in it at any rate.”

“That’s a comfort, certainly, but I’ll tell you one thing: it proves, Johnson, we must be a great distance from any coast. The nearer the coast, the more numerous the icebergs in general, and you see there is not one in sight.”

“The horizon is rather misty, though.”

“So it is, but ever since we started, we have been on this same interminable ice-field.”

“Do you know, Mr. Clawbonny, that smooth as this ice is, we are going over most dangerous ground? Fathomless abysses lie beneath our feet.”

“That’s true enough, but they won’t engulph us. This white sheet over them is pretty tough, I can tell you. It is always getting thicker too; for in these latitudes, it snows nine days out of ten even in April and May; ay, and in June as well. The ice here, in some parts, cannot be less than between thirty and forty feet thick.”

“That sounds reassuring, at all events.” said Johnson.

“Yes, we’re not like the skaters on the Serpentine — always in danger of falling through. This ice is strong enough to bear the weight of the Custom House in Liverpool, or the Houses of Parliament in Westminster.”

“Can they reckon pretty nearly what ice will bear, Mr. Clawbonny?” asked the old sailor, always eager for information.

“What can’t be reckoned now-a-days? Yes, ice two inches thick will bear a man; three and a half inches, a man on horse-back; five inches, an eight pounder; eight inches, field artillery; and ten inches, a whole army.”

“It is difficult to conceive of such a power of resistance, but you were speaking of the incessant snow just now, and I cannot help wondering where it comes from, for the water all round is frozen, and what makes the clouds?”

“That’s a natural enough question, but my notion is that nearly all the snow or rain that we get here comes from the temperate zones. I fancy each of those snowflakes was originally a drop of water in some river, caught up by evaporation into the air, and wafted over here in the shape of clouds; so that it is not impossible that when we quench our thirst with the melted snow, we are actually drinking from the very rivers of our own native land.”

Just at this moment the conversation was interrupted by Hatteras, who called out that they were getting out of the straight line. The increasing mist made it difficult to keep together, and at last, about eight o’clock, they determined to come to a halt, as they had gone fifteen miles. The tent was put up and the stove lighted, and after their usual supper they lay down and slept comfortably till morning.

The calm atmosphere was highly favourable, for though the cold became intense, and the mercury was always frozen in the thermometer, they found no difficulty in continuing their route, confirming the truth of Parry’s assertion that any man suitably clad may walk abroad with impunity in the lowest temperature, provided there is no wind; while, on the other hand, the least breeze would make the skin smart acutely, and bring on violent headache, which would soon end in death.

On the 5th of March a peculiar phenomenon occurred. The sky was perfectly clear and glittering with stars, when suddenly snow began to fall thick and fast, though there was not a cloud in the heavens and through the white flakes the constellations could be seen shining. This curious display lasted two hours, and ceased before the Doctor could arrive at any satisfactory conclusion as to its cause.

The moon had ended her last quarter, and complete darkness prevailed now for seventeen hours out of the twenty-four. The travellers had to fasten themselves together with a long rope to avoid getting separated, and it was all but impossible to pursue the right course. Moreover, the brave fellows, in spite of their iron will, began to show signs of fatigue. Halts became more frequent, and yet every hour was precious, for the provisions were rapidly coming to an end.

Hatteras hardly knew what to think as day after day went on without apparent result, and he asked himself sometimes whether the Porpoise had any actual existence except in Altamont’s fevered brain, and more than once the idea even came into his head that perhaps national hatred might have induced the American to drag them along with himself to certain death.

He told the Doctor his suppositions, who rejected them absolutely, and laid them down to the score of the unhappy rivalry that had arisen already between the two captains.

On the 14th of March, after sixteen days’ march the little party found themselves only yet in the 82º latitude. Their strength was exhausted, and they had a hundred miles more to go. To increase their sufferings, rations had to be still further reduced. Each man must be content with a fourth part to allow the dogs their full quantity.

Unfortunately they could not rely at all on their guns, for only seven charges of powder were left, and six balls. They had fired at several hares and foxes on the road already, but unsuccessfully.

However, on the 15th, the Doctor was fortunate enough to surprise a seal basking on the ice, and, after several shots, the animal was captured and killed.

Johnson soon had it skinned and cut in pieces, but it was so lean that it was worthless as food, unless its captors would drink the oil like the Esquimaux.

The Doctor was bold enough to make the attempt, but failed in spite of himself.

Next day several icebergs and hummocks were noticed on the horizon. Was this a sign that land was near, or was it some ice-field that had broken up? It was difficult to know what to surmise.

On arriving at the first of these hummocks, the travellers set to work to make a cave in it where they could rest more comfortably than in the tent, and after three hours’ persevering toil, were able to light their stove and lie down beside it to stretch their weary limbs.

Chapter 4. The Last Charge of Powder

Johnson was obliged to take the dogs inside the hut, for they would have been soon frozen outside in such dry weather. Had it been snowing they would have been safe enough, for the snow served as a covering, and kept in the natural heat of the animals.

The old sailor, who made a first-rate dog-driver, tried his beasts with the oily flesh of the seal; and found, to his joyful surprise, that they ate it greedily. The Doctor said he was not astonished at this, as in North America the horses were chiefly fed on fish; and he thought that what would satisfy an herbivorous horse might surely content an omnivorous dog.

The whole party were soon buried in deep sleep, for they were fairly overcome with fatigue. Johnson awoke his companions early next morning, and the march was resumed in haste. Their lives depended now on their speed, for provisions would only hold out three days longer.

The sky was magnificent; the atmosphere extremely clear, and the temperature very low. The sun rose in the form of a long ellipse, owing to refraction, which made his horizontal diameter appear twice the length of his vertical.

The Doctor, gun in hand, wandered away from the others, braving the solitude and the cold in the hope of discovering game. He had only sufficient powder left to load three times, and he had just three balls. That was little enough should he encounter a bear, for it often takes ten or twelve shots to have any effect on these enormous animals.

But the brave Doctor would have been satisfied with humbler game. A few hares or foxes would be a welcome addition to their scanty food; but all that day, if even he chanced to see one, either he was too far away, or he was deceived by refraction, and took a wrong aim. He came back to his companions at night with crestfallen looks, having wasted one ball and one charge of powder.

Next day the route appeared more difficult, and the weary men could hardly drag themselves along. The dogs had devoured even the entrails of the seal, and began to gnaw their traces.

A few foxes passed in the distance, and the Doctor lost another ball in attempting to shoot them.

They were forced to come to a halt early in the evening, though the road was illumined by a splendid Aurora Borealis; for they could not put one foot before the other.

Their last meal, on the Sunday evening, was a very sad one — if no providential help came, their doom was sealed.

Johnson set a few traps before going to sleep, though he had no baits to put inside them. He was very disappointed to find them all empty in the morning, and was returning gloomily to the hut, when he perceived a bear of huge dimensions. The old sailor took it into his head that Heaven had sent this beast specially for him to kill; and without waking his comrades, he seized the Doctor’s gun, and was soon in pursuit of his prey. On reaching the right distance, he took aim; but, just as his finger touched the trigger, he felt his arm tremble. His thick gloves hampered him, and, flinging them hastily off, he took up the gun with a firmer grasp. But what a cry of agony escaped him! The skin of his fingers stuck to the gun as if it had been

red-hot, and he was forced to let it drop. The sudden fall made it go off, and the last ball was discharged in the air.

The Doctor ran out at the noise of the report, and understood all at a glance. He saw the animal walking quietly off, and poor Johnson forgetting his sufferings in his despair.

“I am a regular milksop!” he exclaimed, “a cry-baby, that can’t stand the least pain! And at my age, too!”

“Come, Johnson; go in at once, or you will be frost-bitten. Look at your hands — they are white already! Come, come this minute.”

“I am not worth troubling about, Mr. Clawbonny,” said the old boatswain. “Never mind me!”

“But you must come in, you obstinate fellow. Come, now, I tell you; it will be too late presently.”

At last he succeeded in dragging the poor fellow into the tent, where he made him plunge his hands into a

bowl of water, which the heat of the stove kept in a liquid state, though still cold. Johnson’s hands had hardy touched it before it froze immediately.

“You see it was high time you came in; I should have been forced to amputate soon,” said the Doctor.

Thanks to his endeavours, all danger was over in about an hour, but he was advised to keep his hands at a good distance from the stove for some time still.

That morning they had no breakfast. Pemmican and salt beef were both done. Not a crumb of biscuit remained. They were obliged to content themselves with half a cup of hot coffee, and start off again.

They scarcely went three miles before they were compelled to give up for the day. They had no supper but coffee, and the dogs were so ravenous that they were almost devouring each other.

Johnson fancied he could see the bear following them in the distance, but he made no remark to his companions. Sleep forsook the unfortunate men, and their eyes grew wild and haggard.

Tuesday morning came, and it was thirty-four hours since they had tasted a morsel of food. Yet these brave, stout-hearted men continued their march, sustained by their superhuman energy of purpose. They pushed the sledge themselves, for the dogs could no longer draw it.

At the end of two hours, they sank exhausted. Hatteras urged them to make a fresh attempt, but his entreaties and supplications were powerless; they could not do impossibilities.

“Well, at any rate,” he said, “I won’t die of cold if I must of hunger.” He set to work to hew out a hut in an iceberg, aided by Johnson, and really they looked like men digging their own tomb.

It was hard labour, but at length the task was accomplished. The little house was ready, and the miserable men took up their abode in it.

In the evening, while the others lay motionless, a sort of hallucination came over Johnson, and he began raving about bears.

The Doctor roused himself from his torpor, and asked the old man what he meant, and what bear he was talking about.

“The bear that is following us,” replied Johnson.

“A bear following us?”

“Yes, for the last two days!”

“For the last two days! You have seen him?”

“Yes, about a mile to leeward.”

“And you never told me, Johnson!”

“What was the good!”

“True enough,” said the Doctor; “we have not a single bail to send after him!”

“No, not even a bit of iron!”

The Doctor was silent for a minute, as if thinking. Then he said —

“Are you quite certain the animal is following us?”

“Yes, Mr. Clawbonny, he is reckoning on a good feed of human flesh!”

“Johnson!” exclaimed the Doctor, grieved at the despairing mood of his companion.

“He is sure enough of his meal!” continued the

“You have no ball!”

“I’ll make one.”

“You have no lead!”

“No, but I have mercury.”

So saying, he took the thermometer, which stood at 50° above zero, and went outside and laid it on a block of ice. Then he came in again, and said, “Tomorrow! Go to sleep, and wait till the sun rises.”

With the first streak of dawn next day, the Doctor and Johnson rushed out to look at the thermometer. All the mercury had frozen into a compact cylindrical mass. The Doctor broke the tube and took it out. Here was a hard piece of metal ready for use.

“It is wonderful, Mr. Clawbonny; you ought to be a proud man.”

“Not at all, my friend, I am only gifted with a good memory, and I have read a great deal.”

“How did that help you?”

“Why, I just happened to recollect a fact related by Captain Ross in his voyages. He states that they pierced a plank, an inch thick, with a bullet made of mercury. Oil would even have suited my purpose, for, he adds, that a ball of frozen almond oil splits through a post without breaking in pieces.”

“It is quite incredible!”

“But it is a fact, Johnson. Well, come now, this bit of metal may save our lives. We’ll leave it exposed to the air a little while, and go and have a look for the bear.”

Just then Hatteras made his appearance, and the

Doctor told him his project, and showed him the mercury.

The captain grasped his hand silently, and the three hunters went off in quest of their game.

The weather was very clear, and Hatteras, who was a little ahead of the others, speedily discovered the bear about three hundred yards distant, sitting on his hind quarters sniffing the air, evidently scenting the intruders on his domains.

“There he is!” he exclaimed.

“Hush!” cried the Doctor.

But the enormous quadruped, even when he perceived his antagonists, never stirred, and displayed neither fear nor anger. It would not be easy to get near him, however, and Hatteras said —

“Friends, this is no idle sport, our very existence is at stake; we must act prudently.”

“Yes,” replied the Doctor, “for we have but the one shot to depend upon. We must not miss, for if Away they went, while the old boatswain slipped behind a hummock, which completely hid him from the bear, who continued still in the same place and in the same position.

Chapter 5. The Seal and the Bear

“You know, Doctor,” said Hatteras, as they returned to the hut, “the polar bears subsist almost entirely on seals. They’ll lie in wait for them beside the crevasses for whole days, ready to strangle them the moment their heads appear above the surface. It is not likely, then, that a bear will be frightened of a seal.”

“I think I see what you are after, but it is dangerous.”

“Yes, but there is more chance of success than in trying any other plan, so I mean to risk it. I am going to dress myself in the seal’s skin, and creep along the ice. Come, don’t let us lose time. Load the gun and give it me.”

The Doctor could not say anything, for he would have done the same himself, so he followed Hatteras silently to the sledge, taking with him a couple of hatchets for his own and Johnson’s use.

Hatteras soon made his toilette, and slipped into the skin, which was big enough to cover him almost entirely.

“Now, then, give me the gun,” he said, “and you be off to Johnson. I must try and steal a march on my adversary.”

“Courage, Hatteras!” said the Doctor, handing him the weapon, which he had carefully loaded meanwhile.

“Never fear! but be sure you don’t show yourselves till I fire.”

The Doctor soon joined the old boatswain behind the hummock, and told him what they had been doing. The bear was still there, but moving restlessly about, as if he felt the approach of danger.

In a quarter of an hour or so the seal made his appearance on the ice. He had gone a good way round, so as to come on the bear by surprise, and every movement was so perfect an imitation of a seal, that even the Doctor would have been deceived if he had not known it was Hatteras.

“It is capital!” said Johnson, in a low voice. The bear had instantly caught sight of the supposed seal, for he gathered himself up, preparing to make a spring as the animal came nearer, apparently seeking to return to his native element, and unaware of the enemy’s proximity. Bruin went to work with extreme prudence, though his eyes glared with greedy desire to clutch the coveted prey, for he had probably been fasting a month, if not two. He allowed his victim to get within ten paces of him, and then sprang forward with a tremendous bound, but stopped short, stupefied and frightened, within three steps of Hatteras, who started up that moment, and, throwing off his disguise, knelt on one knee, and aimed straight at the bear’s heart. He fired, and the huge monster rolled back on the ice.

“Forward! Forward!” shouted the Doctor, hurrying towards Hatteras, for the bear had reared on his hind legs, and was striking the air with one paw and tearing up the snow to stanch his wound with the other.

Hatteras never moved, but waited, knife in hand. He had aimed well, and fired with a sure and steady aim. Before either of his companions came up he had plunged the knife in the animal’s throat, and made an end of him, for he fell down at once to rise no more.

“Hurrah! Bravo!” shouted Johnson and the Doctor, but Hatteras was as cool and unexcited as possible, and stood with folded arms gazing at his prostrate foe.

“It is my turn now,” said Johnson. “It is a good thing the bear is killed, but if we leave him out here much longer, he will get as hard as a stone, and we shall be able to do nothing with him.”

He began forthwith to strip the skin off, and a fine business it was, for the enormous quadruped was almost as large as an ox. It measured nearly nine feet long, and four round, and the great tusks in his jaws were three inches long.

On cutting the carcase open, Johnson found nothing but water in the stomach. The beast had evidently had no food for a long time, yet it was very fat, and weighed fifteen hundred pounds. The hunters were so famished that they had hardly patience to carry home the flesh to be cooked, and it needed all the Doctor’s persuasion to prevent them eating it raw.

On entering the hut, each man with a load on his back, Clawbonny was struck with the coldness that pervaded the atmosphere. On going up to the stove he found the fire black out. The exciting business of the morning had made Johnson neglect his accustomed duty of replenishing the stove.

The Doctor tried to blow the embers into a flame, but finding he could not even get a red spark, he went out to the sledge to fetch tinder, and get the steel from Johnson.

The old sailor put his hand into his pocket, but was surprised to find the steel missing. He felt in the other pockets, but it was not there. Then he went into the hut again, and shook the blanket he had slept in all night, but his search was still unsuccessful.

He went back to his companions and said —

“Are you sure, Doctor, you haven’t the steel?”

“Quite, Johnson.”

“And you haven’t it either, captain?”

“Not I!” replied Hatteras.

“It has always been in your keeping,” said the Doctor.

“Well, I have not got it now!” exclaimed Johnson, turning pale.

“Not got the steel!” repeated the Doctor, shuddering involuntarily at the bare idea of its loss, for it was all the means they had of procuring a fire.

“Look again, Johnson,” he said.

The boatswain hurried to the only remaining place he could think of, the hummock where he had stood to watch the bear. But the missing treasure was nowhere to be found, and the old sailor returned in despair.

Hatteras looked at him, but no word of reproach escaped his lips. He only said —

“This is a serious business, Doctor.”

“It is, indeed!” said Clawbonny.

“We have not even an instrument, some glass that we might take the lens out of, and use like a burning glass.”

“No, and it is a great pity, for the sun’s rays are quite strong enough just now to light our tinder.”

“Well,” said Hatteras, “we must just appease our hunger with the raw meat, and set off again as soon as we can, to try to discover the ship.”

“Yes!” replied Clawbonny, speaking to himself, absorbed in his own reflections. “Yes, that might do at a pinch! Why not? We might try.”

“What are you dreaming about?” asked Hatteras.

“An idea has just occurred to me.”

“An idea come into your head, Doctor,” exclaimed Johnson; “then we are saved!”

“Will it succeed? that’s the question.”

“What’s your project?” said Hatteras.

“We want a lens; well, let us make one.”

“How?” asked Johnson.

“With a piece of ice.”

“What? Do you think that would do?”

“Why not? All that is needed is to collect the sun’s rays into one common focus, and ice will serve that purpose as well as the finest crystal.”

“Is it possible?” said Johnson.

“Yes, only I should like fresh water ice, it is harder and more transparent than the other.”

“There it is to your hand, if I am not much mistaken,” said Johnson, pointing to a hummock close by. “I fancy that is fresh water, from the dark look of it, and the green tinge.”

“You are right. Bring your hatchet, Johnson.”

A good-sized piece was soon cut off, about a foot in diameter, and the Doctor set to work. He began by chopping it into rough shape with the hatchet; then he operated upon it more carefully with his knife, making as smooth a surface as possible, and finished the polishing process with his fingers, rubbing away until he had obtained as transparent a lens as if it had been made of magnificent crystal.

The sun was shining brilliantly enough for the Doctor’s experiment. The tinder was fetched, and held beneath the lens so as to catch the rays in full power. In a few seconds it took fire, to Johnson’s rapturous delight.

He danced about like an idiot, almost beside himself with joy, and shouted, “Hurrah! hurrah!” while Clawbonny hurried back into the hut and rekindled the fire. The stove was soon roaring, and it was not many minutes before the savoury odour of broiled bear-steaks roused Bell from his torpor.

What a feast this meal was to the poor starving men may be imagined. The Doctor, however, counselled moderation in eating, and set the example himself.

“This is a glad day for us,” he said, “and we have no fear of wanting food all the rest of our journey. Still we must not forget we have further to go yet, and I think the sooner we start the better.”

“We cannot be far off now,” said Altamont, who could almost articulate perfectly again; “we must be within forty-eight hours’ march of the Porpoise.”

“I hope we’ll find something there to make a fire with,” said the Doctor, smiling. “My lens does well enough at present; but it needs the sun, and there are plenty of days when he does not make his appearance here, within less than four degrees of the pole.”

“Less than four degrees!” repeated Altamont, with a sigh; “yes, my ship went further than any other has ever ventured.”

“It is time we started,” said Hatteras, abruptly.

“Yes,” replied the Doctor, glancing uneasily at the two captains.

The dogs were speedily harnessed to the sledge, and the march resumed.

As they went along, the Doctor tried to get out of Altamont the real motive that had brought him so far north. But the American made only evasive replies, and Clawbonny whispered in old Johnson’s ear —

“Two men we’ve got that need looking after.”

“You are right,” said Johnson.

“Hatteras never says a word to this American, and I must say the man has not shown himself very grateful. I am here, fortunately.”

“Mr. Clawbonny,” said Johnson, “now this Yankee has come back to life again, I must confess I don’t much like the expression of his face.”

“I am much mistaken if he does not suspect the projects of Hatteras.”

“Do you think his own were similar?”

“Who knows? These Americans, Johnson, are bold, daring fellows. It is likely enough an American would try to do as much as an Englishman.”

“Then you think that Altamont —”

“I think nothing about it, but his ship is certainly on the road to the North Pole.”

“But didn’t Altamont say that he had been caught among the ice, and dragged there irresistibly?”

“He said so, but I fancied there was a peculiar smile on his lips while he spoke.”

“Hang it! It would be a bad job, Mr. Clawbonny, if any feeling of rivalry came between two men of their stamp.”

“Heaven forfend! for it might involve the most serious consequences, Johnson.”

“I hope Altamont will remember he owes his life to us?”

“But do we not owe ours to him now? I grant, without us, he would not be alive at this moment, but without him and his ship, what would become of us?”

“Well, Mr. Clawbonny, you are here to keep things straight anyhow, and that is a blessing.”

“I hope I may manage it, Johnson.”

The journey proceeded without any fresh incident, but on the Saturday morning the travellers found themselves in a region of quite an altered character. Instead of the wide smooth plain of ice that had hitherto stretched before them, overturned icebergs and broken hummocks covered the horizon; while the frequent blocks of fresh-water ice showed that some coast was near.

Next day, after a hearty breakfast off the bear’s paws, the little party continued their route; but the road became toilsome and fatiguing. Altamont lay watching the horizon with feverish anxiety — an anxiety shared by all his companions, for, according to the last reckoning made by Hatteras, they were now exactly in latitude 83° 35” and longitude 120° 15”, and the question of life or death would be decided before the day was over.

At last, about two o’clock in the afternoon, Altamont started up with a shout that arrested the whole party, and pointing to a white mass that no eye but his could have distinguished from the surrounding icebergs, exclaimed in a loud, ringing voice, “The Porpoise.”

Chapter 6. The Porpoise

It was the 24th of March, and Palm Sunday, a bright, joyous day in many a town and village of the Old World, but in this desolate region what mournful silence prevailed! No willow branches here with their silvery blossom — not even a single withered leaf to be seen — not a blade of grass!

Yet this was a glad day to the travellers, for it promised them speedy deliverance from the death that had seemed so inevitable.

They hastened onward, the dogs put forth renewed energy, and Duk barked his loudest, till, before long, they arrived at the ship. The Porpoise was completely buried under the snow. All her masts and rigging had been destroyed in the shipwreck, and she was lying on a bed of rocks so entirely on her side that her hull was uppermost.

They had to knock away fifteen feet of ice before they could even catch a glimpse of her, and it was not without great difficulty that they managed to get on board, and made the welcome discovery that the provision stores had not been visited by any four-footed marauders. It was quite evident, however, that the ship was not habitable.

“Never mind!” said Hatteras, “we must build a snow-house, and make ourselves comfortable on land.”

“Yes, but we need not hurry over it,” said the Doctor; “let us do it well while we’re about it, and for a time we can make shift on board; for we must build a good, substantial house, that will protect us from the bears as well as the cold. I’ll undertake to be the architect, and you shall see what a first-rate job I’ll make of it.”

“I don’t doubt your talents, Mr. Clawbonny,” replied Johnson; “but, meantime, let us see about taking up our abode here, and making an inventory of the stores we find. There does not seem a boat visible of any description, and I fear these timbers are in too bad a condition to build a new ship out of them.”

“I don’t know that,” returned Clawbonny, “time and thought do wonders; but our first business is to build a house, and not a ship; one thing at a time, I propose.”

“And quite right too,” said Hatteras; “so we’ll go ashore again.”

They returned to the sledge, to communicate the result of their investigation to Bell and Altamont; and about four in the afternoon the five men installed themselves as well as they could on the wreck. Bell had managed to make a tolerably level floor with planks and spars; the stiffened cushions and hammocks were placed round the stove to thaw, and were soon fit for use. Altamont, with the Doctor’s assistance, got on board without much trouble, and a sigh of satisfaction escaped him as if he felt himself once more at home — a sigh which to Johnson’s ear boded no good.

The rest of the day was given to repose, and they wound up with a good supper off the remains of the bear, backed by a plentiful supply of biscuit and hot tea.

It was late next morning before Hatteras and his companions woke, for their minds were not burdened now with any solicitudes about the morrow, and they might sleep as long as they pleased. The poor fellows felt like colonists safely arrived at their destination, who had forgotten all the sufferings of the voyage, and thought only of the new life that lay before them.

“Well, it is something at all events,” said the Doctor, rousing himself and stretching his arms, “for a fellow not to need to ask where he is going to find his next bed and breakfast.”

“Let us see what there is on board before we say much,” said Johnson.

The Porpoise has been thoroughly equipped and provisioned for a long voyage, and, on making an inventory of what stores remained, they found 6150 lbs. of flour, fat, and raisins; 2000 lbs. of salt beef and pork, 1500 lbs. of pemmican; 700 lbs. of sugar, and the same of chocolate; a chest and a half of tea, weighing 96 lbs.; 500 lbs. of rice; several barrels of preserved fruits and vegetables; a quantity of lime-juice, with all sorts of medicines, and 300 gallons of rum and brandy. There was also a large supply of gunpowder, ball, and shot, and coal and wood in abundance.

Altogether, there was enough to last those five men for more than two years, and all fear of death from starvation or cold was at an end.

“Well, Hatteras, we’re sure of enough to live on now,” said the Doctor, “and there is nothing to hinder us reaching the Pole.”

“The Pole!” echoed Hatteras.

“Yes, why not? Can’t we push our way overland in the summer months?”

“We might overland; but how could we cross water?”

“Perhaps we may be able to build a boat out of some of the ship’s planks.”

“Out of an American ship!” exclaimed the captain, contemptuously.

Clawbonny was prudent enough to make no reply, and presently changed the conversation by saying —

“Well, now we have seen what we have to depend upon, we must begin our house and store-rooms. We have materials enough at hand; and, Bell, I hope you are going to distinguish yourself,” he added.

“I am ready, Mr. Clawbonny,” replied Bell; “and, as for material, there is enough for a town here with houses and streets.”

“We don’t require that; we’ll content ourselves with imitating the Hudson’s Bay Company. They entrench themselves in fortresses against the Indians and wild beasts. That’s all we need — a house one side and stores the other, with a wall and two bastions. I must try to make a plan.”

“Ah! Doctor, if you undertake it,” said Johnson, “I am sure you’ll make a good thing of it.”

“Well, the first part of the business is to go and choose the ground. Will you come with us Hatteras?”

“I’ll trust all that to you, Doctor,” replied the captain. “I’m going to look along the coast.”

Altamont was too feeble yet to take part in any work, so he remained on the ship, while the others commenced to explore the unknown continent.

On examining the coast, they found that the Porpoise was in a sort of bay bristling with dangerous rocks, and that to the west, far as the eye could reach, the sea extended, entirely frozen now, though if Belcher and Penny were to be believed, open during the summer months. Towards the north, a promontory stretched out into the sea, and about three miles away was an island of moderate size. The roadstead thus formed would have afforded safe anchorage to ships, but for the difficulty of entering it. A considerable distance inland there was a solitary mountain, about 3000 feet high, by the Doctor’s reckoning; and half-way up the steep rocky cliffs that rose from the shore, they noticed a circular plateau, open on three sides to the bay and sheltered on the fourth by a precipitous wall, 120 feet high.

This seemed to the Doctor the very place for this house, from its naturally fortified situation. By cutting steps in the ice, they managed to climb up and examine it more closely.

They were soon convinced they could not have a better foundation, and resolved to commence operations forthwith, by removing the hard snow more than ten feet deep, which covered the ground, as both dwelling and storehouses must have a solid foundation.

This preparatory work occupied the whole of Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday. At last they came to hard granite close in grain, and containing garnets and felspar crystals, which flew out with every stroke of the pickaxe.

The dimensions and plan of the snow-house were then settled by the Doctor. It was to be divided into three rooms, as all they needed was a bed-room, sitting-room and kitchen. The sitting-room was to be in the middle, the kitchen to the left, and the bed-room to the right.

For five days they toiled unremittingly. There was plenty of material, and the walls required to be thick enough to resist summer thaws. Already the house began to present an imposing appearance. There were four windows in front, made of splendid sheets of ice, in Esquimaux fashion, through which the light came softly in as if through frosted glass.

Outside there was a long covered passage between the two windows of the sitting-room. This was the entrance hall, and it was shut in by a strong door taken from the cabin of the Porpoise. The Doctor was highly delighted with his performance when all was finished, for though it would have been difficult to say to what style of architecture it belonged, it was strong, and that was the chief thing.

The next business was to move in all the furniture of the Porpoise. The beds were brought first and laid down round the large stove in the sleeping room; then came chairs, tables, arm-chairs, cupboards, and benches for the sitting-room, and finally the ship furnaces and cooking utensils for the kitchen. Sails spread on the ground did duty for carpets, and also served for inner doors.

The walls of the house were over five feet thick, and the windows resembled port-holes for cannon. Every part was as solid as possible, and what more was wanted? Yet if the Doctor could have had his way, he would have made all manner of ornamental additions, in humble imitation of the Ice Palace built in St. Petersburgh in January, 1740, of which he had read an account. He amused his companions after work in the evening by describing its grandeur, the cannons in front, and statues of exquisite beauty, and the wonderful elephant that spouted water out of his trunk by day and flaming naphtha by night — all cut out of ice. He also depicted the interior, with tables, and toilette tables, mirrors, candelabra, tapers, beds, mattresses, pillows, curtains, time-pieces, chairs, playing-cards, wardrobes, completely fitted up — in fact, everything in the way of furniture that could be mentioned, and the whole entirely composed of ice.

It was on Easter Sunday, the 31st of March, when the travellers installed themselves in their new abode and after holding divine service in the sitting-room, they devoted the remainder of the day to rest.

Next morning they set about building the storehouses and powder magazine. This took a whole week longer, including the time spent in unloading the vessel, which was a task of considerable difficulty, as the temperature was so low, that they could not work for many hours at a time. At length on the 8th of April, provisions, fuel, and ammunition were all safe on terra firma, and deposited in their respective places. A sort of kennel was constructed a little distance from the house for the Greenland dogs, which the Doctor dignified by the name of “Dog Palace.” Duk shared his master’s quarters.

All that now remained to be done was to put a parapet right round the plateau by way of fortification.

By the 15th this was also completed, and the snow-house might bid defiance to a whole tribe of Esquimaux, or any other hostile invaders, if indeed any human beings whatever were to be found on this unknown continent, for Hatteras, who had minutely examined the bay and the surrounding coast, had not been able to discover the least vestiges of the huts that are generally met with on shores frequented by Greenland tribes. The shipwrecked sailors of the Porpoise and Forward seemed to be the first whose feet had ever trod this lone region.

Chapter 7. An Important Discussion

While all these preparations for winter were going on Altamont was fast regaining strength. His vigorous constitution triumphed, and he was even able to lend a helping hand in the unlading of the ship. He was a true type of the American, a shrewd, intelligent man, full of energy and resolution, enterprising, bold, and ready for anything. He was a native of New York, he informed his companions, and had been a sailor from his boyhood.

The Porpoise had been equipped and sent out by a company of wealthy merchants belonging to the States, at the head of which was the famous Grinnell.

There were many points of resemblance between Altamont and Hatteras, but no affinities. Indeed, any similarity that there was between them, tended rather to create discord than to make the men friends. With a greater show of frankness, he was in reality far more deep and crafty than Hatteras. He was more free and easy, but not so true-hearted, and somehow his apparent openness did not inspire such confidence as the Englishman’s gloomy reserve.

The Doctor was in constant dread of a collision between the rival captains, and yet one must command inevitably, and which should it be! Hatteras had the men, but Altamont had the ship, and it was hard to say whose was the better right.

It required all the Doctor’s tact to keep things smooth, for the simplest conversation threatened to lead to strife.

At last, in spite of all his endeavours, an outbreak occurred on the occasion of a grand banquet by way of “house-warming,” when the new habitation was completed.

This banquet was Dr Clawbonny’s idea. He was head-cook, and distinguished himself by the concoction of a wonderful pudding, which would positively have done no dishonour to the cuisine of the Lord Chancellor of England.

Bell most opportunely chanced to shoot a white hare and several ptarmigans, which made an agreeable variety from the pemmican and salt meat.

Clawbonny was master of the ceremonies, and brought in his pudding, adorning himself with the insignia of his office — a big apron, and a knife dangling at his belt.

As Altamont did not conform to the teetotal régime of his English companions, gin and brandy were set on the table after dinner, and the others, by the Doctor’s orders, joined him in a glass for once, that the festive occasion might be duly honoured. When the different toasts were being drunk, one was given to the United States, to which Hatteras made no response.

This important business over, the Doctor introduced an interesting subject of conversation by saying —

“My friends, it is not enough to have come thus far in spite of so many difficulties; we have something more yet to do. I propose we should bestow a name on this continent, where we have found friendly shelter and rest, and not only on the continent, but on the several bays, peaks, and promontories that we meet with. This has been invariably done by navigators and is a most necessary proceeding.”

“Quite right,” said Johnson, “when once a place is named, it takes away the feeling of being castaways on an unknown shore.”

“Yes,” added Bell, “and we might be going on some expedition and obliged to separate, or go out hunting, and it would make it much easier to find one another if each locality had a definite name.”

“Very well; then,” said the Doctor, “since we are all agreed, let us go steadily to work.”

Hatteras had taken no part in the conversation as yet, but seeing all eyes fixed on him, he rose at last, and said —

“If no one objects, I think the most suitable name we can give our house is that of its skilful architect, the best man among us. Let us call it ‘Doctor’s House.’ “

“Just the thing!” said Bell.

“First rate!” exclaimed Johnson, “ ‘Doctor’s House!’ “

“We cannot do better,” chimed in Altamont. “Hurrah for Doctor Clawbonny.”

Three hearty cheers were given, in which Duk joined lustily, barking his loudest.

“It is agreed then,” said Hatteras, “that this house is to be called ‘Doctor’s House.’ “

The Doctor, almost overcome by his feelings, modestly protested against the honour; but he was obliged to yield to the wishes of his friends, and the new habitation was formally named “Doctor’s House.”

“Now, then,” said the Doctor, “let us go onto name the most important of our discoveries.”

“There is that immense sea which surrounds us, unfurrowed as yet by a single ship.”

“A single ship!” repeated Altamont. “I think you have forgotten the Porpoise, and yet she certainly did not get here overland,”

“Well, it would not be difficult to believe she had,” replied Hatteras, “to see on what she lies at present.”

“True, enough, Hatteras,” said Altamont, in a piqued tone; “but, after all, is not that better than being blown to atoms like the Forward?”

Hatteras was about to make some sharp retort, but Clawbonny interposed.

“It is not a question of ships, my friends,” he said, “but of a fresh sea.”

“It is no new sea,” returned Altamont; “it is in every Polar chart, and has a name already. It is called the Arctic Ocean, and I think it would be very inconvenient to alter its designation. Should we find out by and by, that, instead of being an ocean it is only a strait or gulf, it will be time enough to alter it then.”

“So be it,” said Hatteras.

“Very well, that is an understood thing, then,” said the Doctor, almost regretting that he had started a discussion so pregnant with national rivalries.

“Let us proceed with the continent where we find ourselves at present,” resumed Hatteras. “I am not aware that any name whatever has been affixed to it, even in the most recent charts.”

He looked at Altamont as he spoke, who met his gaze steadily, and said —

“Possibly you may be mistaken again, Hatteras.”

“Mistaken! What! This unknown continent, this virgin soil ——”

“Has already a name,” replied Altamont, coolly.

Hatteras was silent, but his lip quivered.

“And what name has it, then?” asked the Doctor, rather astonished at Altamont’s affirmation.

“My dear Clawbonny,” replied the American, “it is the custom, not to say the right, of every navigator to christen the soil on which he is the first to set foot. It appears to me, therefore, that it is my privilege and duty on this occasion to exercise my prerogative, and —”

“But, sir,” interrupted Johnson, rather nettled at his sang froid.

“It would be a difficult matter to prove that the Porpoise did not come here, even supposing she reached this coast by land,” continued Altamont, without noticing Johnson’s protest. “The fact is indisputable,” he added looking at Hatteras.

“I dispute the claim,” said the Englishman, restraining himself by a powerful effort. “To name a country, you must first discover it, I suppose, and that you certainly did not do. Besides, but for us, where would you have been, sir, at this moment, pray? Lying twenty feet deep under the snow.”

“And without me, sir,” retorted Altamont, hotly, “without me and my ship, where would you all be at this moment? Dead, from cold and hunger.”

“Come, come, friends,” said the Doctor, “don’t get to words, all that can be easily settled. Listen to me.”

“Mr. Hatteras,” said Altamont, “is welcome to name whatever territories he may discover, should he succeed in discovering any; but this continent belongs to me. I should not even consent to its having two names like Grinnell’s Land, which is also called Prince Albert’s Land, because it was discovered almost simultaneously by an Englishman and an American. This is quite another matter; my right of priority is incontestable. No ship before mine ever touched this shore, no foot before mine ever trod this soil. I have given it a name, and that name it shall keep.”

“And what is that name?” inquired the Doctor.

“New America,” replied Altamont.

Hatteras trembled with suppressed passion, but by a violent effort restrained himself.

“Can you prove to me,” said Altamont, “that an Englishman has set foot here before an American?”

Johnson and Bell said nothing, though quite as much offended as the captain by Altamont’s imperious tone. They felt that reply was impossible.

For a few minutes there was an awkward silence, which the Doctor broke by saying —

“My friends, the highest human law is justice. It includes all others. Let us be just, then, and don’t let any bad feeling get in among us. The priority of Altamont seems to me indisputable. We will take our revenge by and by, and England will get her full share in our future discoveries. Let the name New America stand for the continent itself, but I suppose Altamont has not yet disposed of all the bays, and capes, and headlands it contains, and I imagine there will be nothing to prevent us calling this bay Victoria Bay?”

“Nothing whatever, provided that yonder cape is called Cape Washington,” replied Altamont.

“You might choose a name, sir,” exclaimed Hatteras, almost beside himself with passion, “that is less offensive to an Englishman.”

“But not one which sounds so sweet to an American,” retorted Altamont, proudly.

“Come, come,” said the Doctor, “no discussion on that subject. An American has a perfect right to be proud of his great countryman! Let us honour genius wherever it is met with; and since Altamont has made his choice, let us take our turn next; let the captain ——”

“Doctor!” interrupted Hatteras, “I have no wish that my name should figure anywhere on this continent, seeing that it belongs to America.”

“Is this your unalterable determination?” asked Clawbonny.

“It is.”

The Doctor did not insist further.

“Very well, we’ll have it to ourselves then,” he continued, turning to Johnson and Bell. “We’ll leave our traces behind us. I propose that the island we see out there, about three miles away from the shore, should be called Isle Johnson, in honour of our boatswain,’’

“Oh, Mr. Clawbonny,” began Johnson, in no little confusion.

“And that mountain that we discovered in the west we will call Bell Mount, if our carpenter is willing.”

“It is doing me too much honour,” replied Bell.

“It is simple justice,” returned the Doctor.

“Nothing could be better,” said Altamont.