| Library / Literary Works |

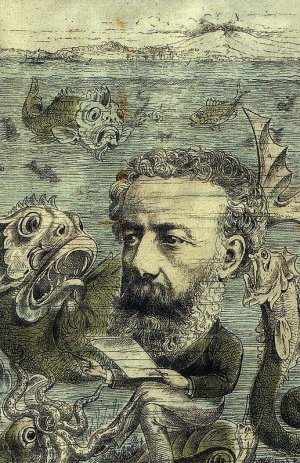

Jules Verne

A Winter Amid the Ice

Table of Contents

1. The Black Flag.

2. Jean Cornbutte’s Project.

3. A Ray of Hope.

4. In the Passes.

5. Liverpool Island.

6. The Quaking of the Ice.

7. Settling for the Winter.

8. Plan of the Explorations.

9. The House of Snow.

10. Buried Alive.

11. A Cloud of Smoke.

12. The Return to the Ship.

13. The Two Rivals.

14. Distress.

15. The White Bears.

16. Conclusion.

Chapter 1. The Black Flag

The curé of the ancient church of Dunkirk rose at five o’clock on the 12th of May, 18 —, to perform, according to his custom, low mass for the benefit of a few pious sinners.

Attired in his priestly robes, he was about to proceed to the altar, when a man entered the sacristy, at once joyous and frightened. He was a sailor of some sixty years, but still vigorous and sturdy, with, an open, honest countenance.

“Monsieur the curé,” said he, “stop a moment, if you please.”

“What do you want so early in the morning, Jean Cornbutte?” asked the curé.

“What do I want? Why, to embrace you in my arms, i’ faith!”

“Well, after the mass at which you are going to be present —”

“The mass?” returned the old sailor, laughing. “Do you think you are going to say your mass now, and that I will let you do so?”

“And why should I not say my mass?” asked the curé. “Explain yourself. The third bell has sounded —”

“Whether it has or not,” replied Jean Cornbutte, “it will sound many more times today, monsieur the curé, for you have promised me that you will bless, with your own hands, the marriage of my son Louis and my niece Marie!”

“He has arrived, then,” said the curé “joyfully.

“It is nearly the same thing,” replied Cornbutte, rubbing his hands. “Our brig was signalled from the look out at sunrise,— our brig, which you yourself christened by the good name of the ‘Jeune–Hardie’!”

“I congratulate you with all my heart, Cornbutte,” said the curé, taking off his chasuble and stole. “I remember our agreement. The vicar will take my place, and I will put myself at your disposal against your dear son’s arrival.”

“And I promise you that he will not make you fast long,” replied the sailor. “You have already published the banns, and you will only have to absolve him from the sins he may have committed between sky and water, in the Northern Ocean. I had a good idea, that the marriage should be celebrated the very day he arrived, and that my son Louis should leave his ship to repair at once to the church.”

“Go, then, and arrange everything, Cornbutte.”

“I fly, monsieur the curé. Good morning!”

The sailor hastened with rapid steps to his house, which stood on the quay, whence could be seen the Northern Ocean, of which he seemed so proud.

Jean Cornbutte had amassed a comfortable sum at his calling. After having long commanded the vessels of a rich shipowner of Havre, he had settled down in his native town, where he had caused the brig “Jeune–Hardie” to be constructed at his own expense. Several successful voyages had been made in the North, and the ship always found a good sale for its cargoes of wood, iron, and tar. Jean Cornbutte then gave up the command of her to his son Louis, a fine sailor of thirty, who, according to all the coasting captains, was the boldest mariner in Dunkirk.

Louis Cornbutte had gone away deeply attached to Marie, his father’s niece, who found the time of his absence very long and weary. Marie was scarcely twenty. She was a pretty Flemish girl, with some Dutch blood in her veins. Her mother, when she was dying, had confided her to her brother, Jean Cornbutte. The brave old sailor loved her as a daughter, and saw in her proposed union with Louis a source of real and durable happiness.

The arrival of the ship, already signalled off the coast, completed an important business operation, from which Jean Cornbutte expected large profits. The “Jeune–Hardie,” which had left three months before, came last from Bodoë, on the west coast of Norway, and had made a quick voyage thence.

On returning home, Jean Cornbutte found the whole house alive. Marie, with radiant face, had assumed her wedding-dress.

“I hope the ship will not arrive before we are ready!” she said.

“Hurry, little one,” replied Jean Cornbutte, “for the wind is north, and she sails well, you know, when she goes freely.”

“Have our friends been told, uncle?” asked Marie.

“They have.”

“The notary, and the curé?”

“Rest easy. You alone are keeping us waiting.”

At this moment Clerbaut, an old crony, came in.

“Well, old Cornbutte,” cried he, “here’s luck! Your ship has arrived at the very moment that the government has decided to contract for a large quantity of wood for the navy!”

“What is that to me?” replied Jean Cornbutte. “What care I for the government?”

“You see, Monsieur Clerbaut,” said Marie, “one thing only absorbs us,— Louis’s return.”

“I don’t dispute that,” replied Clerbaut. “But — in short — this purchase of wood —”

“And you shall be at the wedding,” replied Jean Cornbutte, interrupting the merchant, and shaking his hand as if he would crush it.

“This purchase of wood —”

“And with all our friends, landsmen and seamen, Clerbaut. I have already informed everybody, and I shall invite the whole crew of the ship.”

“And shall we go and await them on the pier?” asked Marie.

“Indeed we will,” replied Jean Cornbutte. “We will defile, two by two, with the violins at the head.”

Jean Cornbutte’s invited guests soon arrived. Though it was very early, not a single one failed to appear. All congratulated the honest old sailor whom they loved. Meanwhile Marie, kneeling down, changed her prayers to God into thanksgivings. She soon returned, lovely and decked out, to the company; and all the women kissed her on the check, while the men vigorously grasped her by the hand. Then Jean Cornbutte gave the signal of departure.

It was a curious sight to see this joyous group taking its way, at sunrise, towards the sea. The news of the ship’s arrival had spread through the port, and many heads, in nightcaps, appeared at the windows and at the half-opened doors. Sincere compliments and pleasant nods came from every side.

The party reached the pier in the midst of a concert of praise and blessings. The weather was magnificent, and the sun seemed to take part in the festivity. A fresh north wind made the waves foam; and some fishing-smacks, their sails trimmed for leaving port, streaked the sea with their rapid wakes between the breakwaters.

The two piers of Dunkirk stretch far out into the sea. The wedding-party occupied the whole width of the northern pier, and soon reached a small house situated at its extremity, inhabited by the harbour-master. The wind freshened, and the “Jeune–Hardie” ran swiftly under her topsails, mizzen, brigantine, gallant, and royal. There was evidently rejoicing on board as well as on land. Jean Cornbutte, spy-glass in hand, responded merrily to the questions of his friends.

“See my ship!” he cried; “clean and steady as if she had been rigged at Dunkirk! Not a bit of damage done,— not a rope wanting!”

“Do you see your son, the captain?” asked one.

“No, not yet. Why, he’s at his business!”

“Why doesn’t he run up his flag?” asked Clerbaut.

“I scarcely know, old friend. He has a reason for it, no doubt.”

“Your spy-glass, uncle?” said Marie, taking it from him. “I want to be the first to see him.”

“But he is my son, mademoiselle!”

“He has been your son for thirty years,” answered the young girl, laughing, “and he has only been my betrothed for two!”

The “Jeune–Hardie” was now entirely visible. Already the crew were preparing to cast anchor. The upper sails had been reefed. The sailors who were among the rigging might be recognized. But neither Marie nor Jean Cornbutte had yet been able to wave their hands at the captain of the ship.

“Faith! there’s the first mate, André Vasling,” cried Clerbaut.

“And there’s Fidèle Misonne, the carpenter,” said another.

“And our friend Penellan,” said a third, saluting the sailor named.

The “Jeune–Hardie” was only three cables’ lengths from the shore, when a black flag ascended to the gaff of the brigantine. There was mourning on board!

A shudder of terror seized the party and the heart of the young girl.

The ship sadly swayed into port, and an icy silence reigned on its deck. Soon it had passed the end of the pier. Marie, Jean Cornbutte, and all their friends hurried towards the quay at which she was to anchor, and in a moment found themselves on board.

“My son!” said Jean Cornbutte, who could only articulate these words.

The sailors, with uncovered heads, pointed to the mourning flag.

Marie uttered a cry of anguish, and fell into old Cornbutte’s arms.

André Vasling had brought back the “Jeune–Hardie,” but Louis Cornbutte, Marie’s betrothed, was not on board.

Chapter 2. Jean Cornbutte’s Project

As soon as the young girl, confided to the care of the sympathizing friends, had left the ship, André Vasling, the mate, apprised Jean Cornbutte of the dreadful event which had deprived him of his son, narrated in the ship’s journal as follows:—

“At the height of the Maëlstrom, on the 26th of April, the ship, putting for the cape, by reason of bad weather and south-west winds, perceived signals of distress made by a schooner to the leeward. This schooner, deprived of its mizzen-mast, was running towards the whirlpool, under bare poles. Captain Louis Cornbutte, seeing that this vessel was hastening into imminent danger, resolved to go on board her. Despite the remonstrances of his crew, he had the long-boat lowered into the sea, and got into it, with the sailor Courtois and the helmsman Pierre Nouquet. The crew watched them until they disappeared in the fog. Night came on. The sea became more and more boisterous. The “Jeune–Hardie”, drawn by the currents in those parts, was in danger of being engulfed by the Maëlstrom. She was obliged to fly before the wind. For several days she hovered near the place of the disaster, but in vain. The long-boat, the schooner, Captain Louis, and the two sailors did not reappear. André Vasling then called the crew together, took command of the ship, and set sail for Dunkirk.”

After reading this dry narrative, Jean Cornbutte wept for a long time; and if he had any consolation, it was the thought that his son had died in attempting to save his fellow-men. Then the poor father left the ship, the sight of which made him wretched, and returned to his desolate home.

The sad news soon spread throughout Dunkirk. The many friends of the old sailor came to bring him their cordial and sincere sympathy. Then the sailors of the “Jeune–Hardie” gave a more particular account of the event, and André Vasling told Marie, at great length, of the devotion of her betrothed to the last.

When he ceased weeping, Jean Cornbutte thought over the matter, and the next day after the ship’s arrival, when Andre came to see him, said,—

“Are you very sure, André, that my son has perished?”

“Alas, yes, Monsieur Jean,” replied the mate.

“And you made all possible search for him?”

“All, Monsieur Cornbutte. But it is unhappily but too certain that he and the two sailors were sucked down in the whirlpool of the Maëlstrom.”

“Would you like, André, to keep the second command of the ship?”

“That will depend upon the captain, Monsieur Cornbutte.”

“I shall be the captain,” replied the old sailor. “I am going to discharge the cargo with all speed, make up my crew, and sail in search of my son.”

“Your son is dead!” said André obstinately.

“It is possible, Andre,” replied Jean Cornbutte sharply, “but it is also possible that he saved himself. I am going to rummage all the ports of Norway whither he might have been driven, and when I am fully convinced that I shall never see him again, I will return here to die!”

André Vasling, seeing that this decision was irrevocable, did not insist further, but went away.

Jean Cornbutte at once apprised his niece of his intention, and he saw a few rays of hope glisten across her tears. It had not seemed to the young girl that her lover’s death might be doubtful; but scarcely had this new hope entered her heart, than she embraced it without reserve.

The old sailor determined that the “Jeune–Hardie” should put to sea without delay. The solidly built ship had no need of repairs. Jean Cornbutte gave his sailors notice that if they wished to re-embark, no change in the crew would be made. He alone replaced his son in the command of the brig. None of the comrades of Louis Cornbutte failed to respond to his call, and there were hardy tars among them,— Alaine Turquiette, Fidèle Misonne the carpenter, Penellan the Breton, who replaced Pierre Nouquet as helmsman, and Gradlin, Aupic, and Gervique, courageous and well-tried mariners.

Jean Cornbutte again offered André Vasling his old rank on board. The first mate was an able officer, who had proved his skill in bringing the “Jeune–Hardie” into port. Yet, from what motive could not be told, André made some difficulties and asked time for reflection.

“As you will, André Vasling,” replied Cornbutte. “Only remember that if you accept, you will be welcome among us.”

Jean had a devoted sailor in Penellan the Breton, who had long been his fellow-voyager. In times gone by, little Marie was wont to pass the long winter evenings in the helmsman’s arms, when he was on shore. He felt a fatherly friendship for her, and she had for him ah affection quite filial. Penellan hastened the fitting out of the ship with all his energy, all the more because, according to his opinion, André Vasling had not perhaps made every effort possible to find the castaways, although he was excusable from the responsibility which weighed upon him as captain.

Within a week the “Jeune–Hardie” was ready to put to sea. Instead of merchandise, she was completely provided with salt meats, biscuits, barrels of flour, potatoes, pork, wine, brandy, coffee, tea, and tobacco.

The departure was fixed for the 22nd of May. On the evening before, André Vasling, who had not yet given his answer to Jean Cornbutte, came to his house. He was still undecided, and did not know which course to take.

Jean was not at home, though the house-door was open. André went into the passage, next to Marie’s chamber, where the sound of an animated conversation struck his ear. He listened attentively, and recognized the voices of Penellan and Marie.

The discussion had no doubt been going on for some time, for the young girl seemed to be stoutly opposing what the Breton sailor said.

“How old is my uncle Cornbutte?” said Marie.

“Something about sixty years,” replied Penellan.

“Well, is he not going to brave danger to find his son?”

“Our captain is still a sturdy man,” returned the sailor. “He has a body of oak and muscles as hard as a spare spar. So I am not afraid to have him go to sea again!’”

“My good Penellan,” said Marie, “one is strong when one loves! Besides, I have full confidence in the aid of Heaven. You understand me, and will help me.”

“No!” said Penellan. “It is impossible, Marie. Who knows whither we shall drift, or what we must suffer? How many vigorous men have I seen lose their lives in these seas!”

“Penellan,” returned the young girl, “if you refuse me, I shall believe that you do not love me any longer.”

André Vasling understood the young girl’s resolution. He reflected a moment, and his course was determined on.

“Jean Cornbutte,” said he, advancing towards the old sailor, who now entered, “I will go with you. The cause of my hesitation has disappeared, and you may count upon my devotion.”

“I have never doubted you, André Vasling,” replied Jean Cornbutte, grasping him by the hand. “Marie, my child!” he added, calling in a loud voice.

Marie and Penellan made their appearance.

“We shall set sail tomorrow at daybreak, with the outgoing tide,” said Jean. “My poor Marie, this is the last evening that we shall pass together.

“Uncle!” cried Marie, throwing herself into his arms.

“Marie, by the help of God, I will bring your lover back to you!”

“Yes, we will find Louis,” added André Vasling.

“You are going with us, then?” asked Penellan quickly.

“Yes, Penellan, André Vasling is to be my first mate,” answered Jean.

“Oh, oh!” ejaculated the Breton, in a singular tone.

“And his advice will be useful to us, for he is able and enterprising.

“And yourself, captain,” said André. “You will set us all a good example, for you have still as much vigour as experience.”

“Well, my friends, good-bye till tomorrow. Go on board and make the final arrangements. Good-bye, André; good-bye, Penellan.”

The mate and the sailor went out together, and Jean and Marie remained alone. Many bitter tears were shed during that sad evening. Jean Cornbutte, seeing Marie so wretched, resolved to spare her the pain of separation by leaving the house on the morrow without her knowledge. So he gave her a last kiss that evening, and at three o’clock next morning was up and away.

The departure of the brig had attracted all the old sailor’s friends to the pier. The curé, who was to have blessed Marie’s union with Louis, came to give a last benediction on the ship. Rough grasps of the hand were silently exchanged, and Jean went on board.

The crew were all there. André Vasling gave the last orders. The sails were spread, and the brig rapidly passed out under a stiff north-west breeze, whilst the cure, upright in the midst of the kneeling spectators, committed the vessel to the hands of God.

Whither goes this ship? She follows the perilous route upon which so many castaways have been lost! She has no certain destination. She must expect every peril, and be able to brave them without hesitating. God alone knows where it will be her fate to anchor. May God guide her!

Chapter 3. A Ray of Hope.

At that time of the year the season was favourable, and the crew might hope promptly to reach the scene of the shipwreck.

Jean Cornbutte’s plan was naturally traced out. He counted on stopping at the Feroë Islands, whither the north wind might have carried the castaways; then, if he was convinced that they had not been received in any of the ports of that locality, he would continue his search beyond the Northern Ocean, ransack the whole western coast of Norway as far as Bodoë, the place nearest the scene of the shipwreck; and, if necessary, farther still.

André Vasling thought, contrary to the captain’s opinion, that the coast of Iceland should be explored; but Penellan observed that, at the time of the catastrophe, the gale came from the west; which, while it gave hope that the unfortunates had not been forced towards the gulf of the Maëlstrom, gave ground for supposing that they might have been thrown on the Norwegian coast.

It was determined, then, that this coast should be followed as closely as possible, so as to recognize any traces of them that might appear.

The day after sailing, Jean Cornbutte, intent upon a map, was absorbed in reflection, when a small hand touched his shoulder, and a soft voice said in his ear,—

“Have good courage, uncle.”

He turned, and was stupefied. Marie embraced him.

“Marie, my daughter, on board!” he cried.

“The wife may well go in search of her husband, when the father embarks to save his child.”

“Unhappy Marie! How wilt thou support our fatigues! Dost thou know that thy presence may be injurious to our search?”

“No, uncle, for I am strong.”

“Who knows whither we shall be forced to go, Marie? Look at this map. We are approaching places dangerous even for us sailors, hardened though we are to the difficulties of the sea. And thou, frail child?”

“But, uncle, I come from a family of sailors. I am used to stories of combats and tempests. I am with you and my old friend Penellan!”

“Penellan! It was he who concealed you on board?”

“Yes, uncle; but only when he saw that I was determined to come without his help.”

“Penellan!” cried Jean.

Penellan entered.

“It is not possible to undo what you have done, Penellan; but remember that you are responsible for Marie’s life.”

“Rest easy, captain,” replied Penellan. “The little one has force and courage, and will be our guardian angel. And then, captain, you know it is my theory, that all in this world happens for the best.”

The young girl was installed in a cabin, which the sailors soon got ready for her, and which they made as comfortable as possible.

A week later the “Jeune–Hardie” stopped at the Feroë Islands, but the most minute search was fruitless. Mo wreck, or fragments of a ship had come upon these coasts. Even the news of the event was quite unknown. The brig resumed its voyage, after a stay of ten days, about the 10th of June. The sea was calm, and the winds were favourable. The ship sped rapidly towards the Norwegian coast, which it explored without better result.

Jean Cornbutte determined to proceed to Bodoë. Perhaps he would there learn the name of the shipwrecked schooner to succour which Louis and the sailors had sacrificed themselves.

On the 30th of June the brig cast anchor in that port.

The authorities of Bodoë gave Jean Cornbutte a bottle found on the coast, which contained a document bearing these words:—

“This 26th April, on board the ‘Froöern,’ after being accosted by the long-boat of the ‘Jeune–Hardie,’ we were drawn by the currents towards the ice. God have pity on us!”

Jean Cornbutte’s first impulse was to thank Heaven. He thought himself on his son’s track. The “Froöern” was a Norwegian sloop of which there had been no news, but which had evidently been drawn northward.

Not a day was to be lost. The “Jeune–Hardie” was at once put in condition to brave the perils of the polar seas. Fidèle Misonne, the carpenter, carefully examined her, and assured himself that her solid construction might resist the shock of the ice-masses.

Penellan, who had already engaged in whale-fishing in the arctic waters, took care that woollen and fur coverings, many sealskin moccassins, and wood for the making of sledges with which to cross the ice-fields were put on board. The amount of provisions was increased, and spirits and charcoal were added; for it might be that they would have to winter at some point on the Greenland coast. They also procured, with much difficulty and at a high price, a quantity of lemons, for preventing or curing the scurvy, that terrible disease which decimates crews in the icy regions. The ship’s hold was filled with salt meat, biscuits, brandy, &c., as the steward’s room no longer sufficed. They provided themselves, moreover, with a large quantity of “pemmican,” an Indian preparation which concentrates a great deal of nutrition within a small volume.

By order of the captain, some saws were put on board for cutting the ice-fields, as well as picks and wedges for separating them. The captain determined to procure some dogs for drawing the sledges on the Greenland coast.

The whole crew was engaged in these preparations, and displayed great activity. The sailors Aupic, Gervique, and Gradlin zealously obeyed Penellan’s orders; and he admonished them not to accustom themselves to woollen garments, though the temperature in this latitude, situated just beyond the polar circle, was very low.

Penellan, though he said nothing, narrowly watched every action of André Vasling. This man was Dutch by birth, came from no one knew whither, but was at least a good sailor, having made two voyages on board the “Jeune–Hardie”. Penellan would not as yet accuse him of anything, unless it was that he kept near Marie too constantly, but he did not let him out of his sight.

Thanks to the energy of the crew, the brig was equipped by the 16th of July, a fortnight after its arrival at Bodoë. It was then the favourable season for attempting explorations in the Arctic Seas. The thaw had been going on for two months, and the search might be carried farther north. The “Jeune–Hardie” set sail, and directed her way towards Cape Brewster, on the eastern coast of Greenland, near the 70th degree of latitude.

Chapter 4. In the Passes.

About the 23rd of July a reflection, raised above the sea, announced the presence of the first icebergs, which, emerging from Davis’ Straits, advanced into the ocean. From this moment a vigilant watch was ordered to the look-out men, for it was important not to come into collision with these enormous masses.

The crew was divided into two watches. The first was composed of Fidèle Misonne, Gradlin, and Gervique; and the second of Andre Vasling, Aupic, and Penellan. These watches were to last only two hours, for in those cold regions a man’s strength is diminished one-half. Though the “Jeune–Hardie” was not yet beyond the 63rd degree of latitude, the thermometer already stood at nine degrees centigrade below zero.

Rain and snow often fell abundantly. On fair days, when the wind was not too violent, Marie remained on deck, and her eyes became accustomed to the uncouth scenes of the Polar Seas.

On the 1st of August she was promenading aft, and talking with her uncle, Penellan, and André Vasling. The ship was then entering a channel three miles wide, across which broken masses of ice were rapidly descending southwards.

“When shall we see land?” asked the young girl.

“In three or four days at the latest,” replied Jean Cornbutte.

“But shall we find there fresh traces of my poor Louis?”

“Perhaps so, my daughter; but I fear that we are still far from the end of our voyage. It is to be feared that the ‘Froöern’ was driven farther northward.”

“That may be,” added André Vasling, “for the squall which separated us from the Norwegian boat lasted three days, and in three days a ship makes good headway when it is no longer able to resist the wind.”

“Permit me to tell you, Monsieur Vasling.” replied Penellan, “that that was in April, that the thaw had not then begun, and that therefore the ‘Froöern’ must have been soon arrested by the ice.”

“And no doubt dashed into a thousand pieces,” said the mate, “as her crew could not manage her.”

“But these ice-fields,” returned Penellan, “gave her an easy means of reaching land, from which she could not have been far distant.”

“Let us hope so,” said Jean Cornbutte, interrupting the discussion, which was daily renewed between the mate and the helmsman. “I think we shall see land before long.”

“There it is!” cried Marie. “See those mountains!”

“No, my child,” replied her uncle. “Those are mountains of ice, the first we have met with. They would shatter us like glass if we got entangled between them. Penellan and Vasling, overlook the men.”

These floating masses, more than fifty of which now appeared at the horizon, came nearer and nearer to the brig. Penellan took the helm, and Jean Cornbutte, mounted on the gallant, indicated the route to take.

Towards evening the brig was entirely surrounded by these moving rocks, the crushing force of which is irresistible. It was necessary, then, to cross this fleet of mountains, for prudence prompted them to keep straight ahead. Another difficulty was added to these perils. The direction of the ship could not be accurately determined, as all the surrounding points constantly changed position, and thus failed to afford a fixed perspective. The darkness soon increased with the fog. Marie descended to her cabin, and the whole crew, by the captain’s orders, remained on deck. They were armed with long boat-poles, with iron spikes, to preserve the ship from collision with the ice.

The ship soon entered a strait so narrow that often the ends of her yards were grazed by the drifting mountains, and her booms seemed about to be driven in. They were even forced to trim the mainyard so as to touch the shrouds. Happily these precautions did not deprive, the vessel of any of its speed, for the wind could only reach the upper sails, and these sufficed to carry her forward rapidly. Thanks to her slender hull, she passed through these valleys, which were filled with whirlpools of rain, whilst the icebergs crushed against each other with sharp cracking and splitting.

Jean Cornbutte returned to the deck. His eyes could not penetrate the surrounding darkness. It became necessary to furl the upper sails, for the ship threatened to ground, and if she did so she was lost.

“Cursed voyage!” growled André Vasling among the sailors, who, forward, were avoiding the most menacing ice-blocks with their boat-hooks.

“Truly, if we escape we shall owe a fine candle to Our Lady of the Ice!” replied Aupic.

“Who knows how many floating mountains we have got to pass through yet?” added the mate.

“And who can guess what we shall find beyond them?” replied the sailor.

“Don’t talk so much, prattler,” said Gervique, “and look out on your side. When we have got by them, it’ll be time to grumble. Look out for your boat-hook!”

At this moment an enormous block of ice, in the narrow strait through which the brig was passing, came rapidly down upon her, and it seemed impossible to avoid it, for it barred the whole width of the channel, and the brig could not heave-to.

“Do you feel the tiller?” asked Cornbutte of Penellan.

“No, captain. The ship does not answer the helm any longer.”

“Ohé, boys!” cried the captain to the crew; “don’t be afraid, and buttress your hooks against the gunwale.”

The block was nearly sixty feet high, and if it threw itself upon the brig she would be crushed. There was an undefinable moment of suspense, and the crew retreated backward, abandoning their posts despite the captain’s orders.

But at the instant when the block was not more than half a cable’s length from the “Jeune–Hardie,” a dull sound was heard, and a veritable waterspout fell upon the bow of the vessel, which then rose on the back of an enormous billow.

The sailors uttered a cry of terror; but when they looked before them the block had disappeared, the passage was free, and beyond an immense plain of water, illumined by the rays of the declining sun, assured them of an easy navigation.

“All’s well!” cried Penellan. “Let’s trim our topsails and mizzen!”

An incident very common in those parts had just occurred. When these masses are detached from one another in the thawing season, they float in a perfect equilibrium; but on reaching the ocean, where the water is relatively warmer, they are speedily undermined at the base, which melts little by little, and which is also shaken by the shock of other ice-masses. A moment comes when the centre of gravity of these masses is displaced, and then they are completely overturned. Only, if this block had turned over two minutes later, it would have fallen on the brig and carried her down in its fall.

Chapter 5. Liverpool Island.

The brig now sailed in a sea which was almost entirely open. At the horizon only, a whitish light, this time motionless, indicated the presence of fixed plains of ice.

Jean Cornbutte now directed the “Jeune–Hardie” towards Cape Brewster. They were already approaching the regions where the temperature is excessively cold, for the sun’s rays, owing to their obliquity when they reach them, are very feeble.

On the 3rd of August the brig confronted immoveable and united ice-masses. The passages were seldom more than a cable’s length in width, and the ship was forced to make many turnings, which sometimes placed her heading the wind.

Penellan watched over Marie with paternal care, and, despite the cold, prevailed upon her to spend two or three hours every day on deck, for exercise had become one of the indispensable conditions of health.

Marie’s courage did not falter. She even comforted the sailors with her cheerful talk, and all of them became warmly attached to her. André Vasling showed himself more attentive than ever, and seized every occasion to be in her company; but the young girl, with a sort of presentiment, accepted his services with some coldness. It may be easily conjectured that André‘s conversation referred more to the future than to the present, and that he did not conceal the slight probability there was of saving the castaways. He was convinced that they were lost, and the young girl ought thenceforth to confide her existence to some one else.

Marie had not as yet comprehended André‘s designs, for, to his great disgust, he could never find an opportunity to talk long with her alone. Penellan had always an excuse for interfering, and destroying the effect of Andre’s words by the hopeful opinions he expressed.

Marie, meanwhile, did not remain idle. Acting on the helmsman’s advice, she set to work on her winter garments; for it was necessary that she should completely change her clothing. The cut of her dresses was not suitable for these cold latitudes. She made, therefore, a sort of furred pantaloons, the ends of which were lined with seal-skin; and her narrow skirts came only to her knees, so as not to be in contact with the layers of snow with which the winter would cover the ice-fields. A fur mantle, fitting closely to the figure and supplied with a hood, protected the upper part of her body.

In the intervals of their work, the sailors, too, prepared clothing with which to shelter themselves from the cold. They made a quantity of high seal-skin boots, with which to cross the snow during their explorations. They worked thus all the time that the navigation in the straits lasted.

André Vasling, who was an excellent shot, several times brought down aquatic birds with his gun; innumerable flocks of these were always careering about the ship. A kind of eider-duck provided the crew with very palatable food, which relieved the monotony of the salt meat.

At last the brig, after many turnings, came in sight of Cape Brewster. A long-boat was put to sea. Jean Cornbutte and Penellan reached the coast, which was entirely deserted.

The ship at once directed its course towards Liverpool Island, discovered in 1821 by Captain Scoresby, and the crew gave a hearty cheer when they saw the natives running along the shore. Communication was speedily established with them, thanks to Penellan’s knowledge of a few words of their language, and some phrases which we natives themselves had learnt of the whalers who frequented those parts.

These Greenlanders were small and squat; they were not more than four feet ten inches high; they had red, round faces, and low foreheads; their hair, flat and black, fell over their shoulders; their teeth were decayed, and they seemed to be affected by the sort of leprosy which is peculiar to ichthyophagous tribes.

In exchange for pieces of iron and brass, of which they are extremely covetous, these poor creatures brought bear furs, the skins of sea-calves, sea-dogs, sea-wolves, and all the animals generally known as seals. Jean Cornbutte obtained these at a low price, and they were certain to become most useful.

The captain then made the natives understand that he was in search of a shipwrecked vessel, and asked them if they had heard of it. One of them immediately drew something like a ship on the snow, and indicated that a vessel of that sort had been carried northward three months before: he also managed to make it understood that the thaw and breaking up of the ice-fields had prevented the Greenlanders from going in search of it; and, indeed, their very light canoes, which they managed with paddles, could not go to sea at that time.

This news, though meagre, restored hope to the hearts of the sailors, and Jean Cornbutte had no difficulty in persuading them to advance farther in the polar seas.

Before quitting Liverpool Island, the captain purchased a pack of six Esquimaux dogs, which were soon acclimatised on board. The ship weighed anchor on the morning of the 10th of August, and entered the northern straits under a brisk wind.

The longest days of the year had now arrived; that is, the sun, in these high latitudes, did not set, and reached the highest point of the spirals which it described above the horizon.

This total absence of night was not, however, very apparent, for the fog, rain, and snow sometimes enveloped the ship in real darkness.

Jean Cornbutte, who was resolved to advance as far as possible, began to take measures of health. The space between decks was securely enclosed, and every morning care was taken to ventilate it with fresh air. The stoves were installed, and the pipes so disposed as to yield as much heat as possible. The sailors were advised to wear only one woollen shirt over their cotton shirts, and to hermetically close their seal cloaks. The fires were not yet lighted, for it was important to reserve the wood and charcoal for the most intense cold.

Warm beverages, such as coffee and tea, were regularly distributed to the sailors morning and evening; and as it was important to live on meat, they shot ducks and teal, which abounded in these parts.

Jean Cornbutte also placed at the summit of the mainmast a “crow’s nest,” a sort of cask staved in at one end, in which a look-out remained constantly, to observe the icefields.

Two days after the brig had lost sight of Liverpool Island the temperature became suddenly colder under the influence of a dry wind. Some indications of winter were perceived. The ship had not a moment to lose, for soon the way would be entirely closed to her. She advanced across the straits, among which lay ice-plains thirty feet thick.

On the morning of the 3rd of September the “Jeune–Hardie” reached the head of Gaël-Hamkes Bay. Land was then thirty miles to the leeward. It was the first time that the brig had stopped before a mass of ice which offered no outlet, and which was at least a mile wide. The saws must now be used to cut the ice. Penellan, Aupic, Gradlin, and Turquiette were chosen to work the saws, which had been carried outside the ship. The direction of the cutting was so determined that the current might carry off the pieces detached from the mass. The whole crew worked at this task for nearly twenty hours. They found it very painful to remain on the ice, and were often obliged to plunge into the water up to their middle; their seal-skin garments protected them but imperfectly from the damp.

Moreover all excessive toil in those high latitudes is soon followed by an overwhelming weariness; for the breath soon fails, and the strongest are forced to rest at frequent intervals.

At last the navigation became free, and the brig was towed beyond the mass which had so long obstructed her course.

Chapter 6. The Quaking of the Ice.

For several days the “Jeune–Hardie” struggled against formidable obstacles. The crew were almost all the time at work with the saws, and often powder had to be used to blow up the enormous blocks of ice which closed the way.

On the 12th of September the sea consisted of one solid plain, without outlet or passage, surrounding the vessel on all sides, so that she could neither advance nor retreat. The temperature remained at an average of sixteen degrees below zero. The winter season had come on, with its sufferings and dangers.

The “Jeune–Hardie” was then near the 21st degree of longitude west and the 76th degree of latitude north, at the entrance of Gaël-Hamkes Bay.

Jean Cornbutte made his preliminary preparations for wintering. He first searched for a creek whose position would shelter the ship from the wind and breaking up of the ice. Land, which was probably thirty miles west, could alone offer him secure shelter, and he resolved to attempt to reach it.

He set out on the 12th of September, accompanied by André Vasling, Penellan, and the two sailors Gradlin and Turquiette. Each man carried provisions for two days, for it was not likely that their expedition would occupy a longer time, and they were supplied with skins on which to sleep.

Snow had fallen in great abundance and was not yet frozen over; and this delayed them seriously. They often sank to their waists, and could only advance very cautiously, for fear of falling into crevices. Penellan, who walked in front, carefully sounded each depression with his iron-pointed staff.

About five in the evening the fog began to thicken, and the little band were forced to stop. Penellan looked about for an iceberg which might shelter them from the wind, and after refreshing themselves, with regrets that they had no warm drink, they spread their skins on the snow, wrapped themselves up, lay close to each other, and soon dropped asleep from sheer fatigue.

The next morning Jean Cornbutte and his companions were buried beneath a bed of snow more than a foot deep. Happily their skins, perfectly impermeable, had preserved them, and the snow itself had aided in retaining their heat, which it prevented from escaping.

The captain gave the signal of departure, and about noon they at last descried the coast, which at first they could scarcely distinguish. High ledges of ice, cut perpendicularly, rose on the shore; their variegated summits, of all forms and shapes, reproduced on a large scale the phenomena of crystallization. Myriads of aquatic fowl flew about at the approach of the party, and the seals, lazily lying on the ice, plunged hurriedly into the depths.

“I’ faith!” said Penellan, “we shall not want for either furs or game!”

“Those animals,” returned Cornbutte, “give every evidence of having been already visited by men; for in places totally uninhabited they would not be so wild.”

“None but Greenlanders frequent these parts,” said André Vasling.

“I see no trace of their passage, however; neither any encampment nor the smallest hut,” said Penellan, who had climbed up a high peak. “O captain!” he continued, “come here! I see a point of land which will shelter us splendidly from the north-east wind.”

“Come along, boys!” said Jean Cornbutte.

His companions followed him, and they soon rejoined Penellan. The sailor had said what was true. An elevated point of land jutted out like a promontory, and curving towards the coast, formed a little inlet of a mile in width at most. Some moving ice-blocks, broken by this point, floated in the midst, and the sea, sheltered from the colder winds, was not yet entirely frozen over.

This was an excellent spot for wintering, and it only remained to get the ship thither. Jean Cornbutte remarked that the neighbouring ice-field was very thick, and it seemed very difficult to cut a canal to bring the brig to its destination. Some other creek, then, must be found; it was in vain that he explored northward. The coast remained steep and abrupt for a long distance, and beyond the point it was directly exposed to the attacks of the east-wind. The circumstance disconcerted the captain all the more because André Vasling used strong arguments to show how bad the situation was. Penellan, in this dilemma, found it difficult to convince himself that all was for the best.

But one chance remained — to seek a shelter on the southern side of the coast. This was to return on their path, but hesitation was useless. The little band returned rapidly in the direction of the ship, as their provisions had begun to run short. Jean Cornbutte searched for some practicable passage, or at least some fissure by which a canal might be cut across the ice-fields, all along the route, but in vain.

Towards evening the sailors came to the same place where they had encamped over night. There had been no snow during the day, and they could recognize the imprint of their bodies on the ice. They again disposed themselves to sleep with their furs.

Penellan, much disturbed by the bad success of the expedition, was sleeping restlessly, when, at a waking moment, his attention was attracted by a dull rumbling. He listened attentively, and the rumbling seemed so strange that he nudged Jean Cornbutte with his elbow.

“What is that?” said the latter, whose mind, according to a sailor’s habit, was awake as soon as his body.

“Listen, captain.”

The noise increased, with perceptible violence.

“It cannot be thunder, in so high a latitude,” said Cornbutte, rising.

“I think we have come across some white bears,” replied Penellan.

“The devil! We have not seen any yet.”

“Sooner or later, we must have expected a visit from them. Let us give them a good reception.”

Penellan, armed with a gun, lightly crossed the ledge which sheltered them. The darkness was very dense; he could discover nothing; but a new incident soon showed him that the cause of the noise did not proceed from around them.

Jean Cornbutte rejoined him, and they observed with terror that this rumbling, which awakened their companions, came from beneath them.

A new kind of peril menaced them. To the noise, which resembled peals of thunder, was added a distinct undulating motion of the ice-field. Several of the party lost their balance and fell.

“Attention!” cried Penellan.

“Yes!” some one responded.

“Turquiette! Gradlin! where are you?”

“Here I am!” responded Turquiette, shaking off the snow with which he was covered.

“This way, Vasling,” cried Cornbutte to the mate. “And Gradlin?”

“Present, captain. But we are lost!” shouted Gradlin, in fright.

“No!” said Penellan. “Perhaps we are saved!”

Hardly had he uttered these words when a frightful cracking noise was heard. The ice-field broke clear through, and the sailors were forced to cling to the block which was quivering just by them. Despite the helmsman’s words, they found themselves in a most perilous position, for an ice-quake had occurred. The ice masses had just “weighed anchor,” as the sailors say. The movement lasted nearly two minutes, and it was to be feared that the crevice would yawn at the very feet of the unhappy sailors. They anxiously awaited daylight in the midst of continuous shocks, for they could not, without risk of death, move a step, and had to remain stretched out at full length to avoid being engulfed.

As soon as it was daylight a very different aspect presented itself to their eyes. The vast plain, a compact mass the evening before, was now separated in a thousand places, and the waves, raised by some submarine commotion, had broken the thick layer which sheltered them.

The thought of his ship occurred to Jean Cornbutte’s mind.

“My poor brig!” he cried. “It must have perished!”

The deepest despair began to overcast the faces of his companions. The loss of the ship inevitably preceded their own deaths.

“Courage, friends,” said Penellan. “Reflect that this night’s disaster has opened us a path across the ice, which will enable us to bring our ship to the bay for wintering! And, stop! I am not mistaken. There is the ‘Jeune–Hardie,’ a mile nearer to us!”

All hurried forward, and so imprudently, that Turquiette slipped into a fissure, and would have certainly perished, had not Jean Cornbutte seized him by his hood. He got off with a rather cold bath.

The brig was indeed floating two miles away. After infinite trouble, the little band reached her. She was in good condition; but her rudder, which they had neglected to lift, had been broken by the ice.

Chapter 7. Settling for the Winter.

Penellan was once more right; all was for the best, and this ice-quake had opened a practicable channel for the ship to the bay. The sailors had only to make skilful use of the currents to conduct her thither.

On the 19th of September the brig was at last moored in her bay for wintering, two cables’ lengths from the shore, securely anchored on a good bottom. The ice began the next day to form around her hull; it soon became strong enough to bear a man’s weight, and they could establish a communication with land.

The rigging, as is customary in arctic navigation, remained as it was; the sails were carefully furled on the yards and covered with their casings, and the “crow’s-nest” remained in place, as much to enable them to make distant observations as to attract attention to the ship.

The sun now scarcely rose above the horizon. Since the June solstice, the spirals which it had described descended lower and lower; and it would soon disappear altogether.

The crew hastened to make the necessary preparations. Penellan supervised the whole. The ice was soon thick around the ship, and it was to be feared that its pressure might become dangerous; but Penellan waited until, by reason of the going and coming of the floating ice-masses and their adherence, it had reached a thickness of twenty feet; he then had it cut around the hull, so that it united under the ship, the form of which it assumed; thus enclosed in a mould, the brig had no longer to fear the pressure of the ice, which could make no movement.

The sailors then elevated along the wales, to the height of the nettings, a snow wall five or six feet thick, which soon froze as hard as a rock. This envelope did not allow the interior heat to escape outside. A canvas tent, covered with skins and hermetically closed, was stretched aver the whole length of the deck, and formed a sort of walk for the sailors.

They also constructed on the ice a storehouse of snow, in which articles which embarrassed the ship were stowed away. The partitions of the cabins were taken down, so as to form a single vast apartment forward, as well as aft. This single room, besides, was more easy to warm, as the ice and damp found fewer corners in which to take refuge. It was also less difficult to ventilate it, by means of canvas funnels which opened without.

Each sailor exerted great energy in these preparations, and about the 25th of September they were completed. André Vasling had not shown himself the least active in this task. He devoted himself with especial zeal to the young girl’s comfort, and if she, absorbed in thoughts of her poor Louis, did not perceive this, Jean Cornbutte did not fail soon to remark it. He spoke of it to Penellan; he recalled several incidents which completely enlightened him regarding his mate’s intentions; André Vasling loved Marie, and reckoned on asking her uncle for her hand, as soon as it was proved beyond doubt that the castaways were irrevocably lost; they would return then to Dunkirk, and André Vasling would be well satisfied to wed a rich and pretty girl, who would then be the sole heiress of Jean Cornbutte.

But André, in his impatience, was often imprudent. He had several times declared that the search for the castaways was useless, when some new trace contradicted him, and enabled Penellan to exult over him. The mate, therefore, cordially detested the helmsman, who returned his dislike heartily. Penellan only feared that André might sow seeds of dissension among the crew, and persuaded Jean Cornbutte to answer him evasively on the first occasion.

When the preparations for the winter were completed, the captain took measures to preserve the health of the crew. Every morning the men were ordered to air their berths, and carefully clean the interior walls, to get rid of the night’s dampness. They received boiling tea or coffee, which are excellent cordials to use against the cold, morning and evening; then they were divided into hunting-parties, who should procure as much fresh nourishment as possible for every day.

Each one also took healthy exercise every day, so as not to expose himself without motion to the cold; for in a temperature thirty degrees below zero, some part of the body might suddenly become frozen. In such cases friction of the snow was used, which alone could heal the affected part.

Penellan also strongly advised cold ablutions every morning. It required some courage to plunge the hands and face in the snow, which had to be melted within. But Penellan bravely set the example, and Marie was not the last to imitate him.

Jean Cornbutte did not forget to have readings and prayers, for it was needful that the hearts of his comrades should not give way to despair or weariness. Nothing is more dangerous in these desolate latitudes.

The sky, always gloomy, filled the soul with sadness. A thick snow, lashed by violent winds, added to the horrors of their situation. The sun would soon altogether disappear. Had the clouds not gathered in masses above their heads, they might have enjoyed the moonlight, which was about to become really their sun during the long polar night; but, with the west winds, the snow did not cease to fall. Every morning it was necessary to clear off the sides of the ship, and to cut a new stairway in the ice to enable them to reach the ice-field. They easily succeeded in doing this with snow-knives; the steps once cut, a little water was thrown over them, and they at once hardened.

Penellan had a hole cut in the ice, not far from the ship. Every day the new crust which formed over its top was broken, and the water which was drawn thence, from a certain depth, was less cold than that at the surface.

All these preparations occupied about three weeks. It was then time to go forward with the search. The ship was imprisoned for six or seven months, and only the next thaw could open a new route across the ice. It was wise, then, to profit by this delay, and extend their explorations northward.

Chapter 8. Plan of the Explorations.

On the 9th of October, Jean Cornbutte held a council to settle the plan of his operations, to which, that there might be union, zeal, and courage on the part of every one, he admitted the whole crew. Map in hand, he clearly explained their situation.

The eastern coast of Greenland advances perpendicularly northward. The discoveries of the navigators have given the exact boundaries of those parts. In the extent of five hundred leagues, which separates Greenland from Spitzbergen, no land has been found. An island (Shannon Island) lay a hundred miles north of Gaël-Hamkes Bay, where the “Jeune–Hardie” was wintering.

If the Norwegian schooner, as was most probable, had been driven in this direction, supposing that she could not reach Shannon Island, it was here that Louis Cornbutte and his comrades must have sought for a winter asylum.

This opinion prevailed, despite André Vasling’s opposition; and it was decided to direct the explorations on the side towards Shannon Island.

Arrangements for this were at once begun. A sledge like that used by the Esquimaux had been procured on the Norwegian coast. This was constructed of planks curved before and behind, and was made to slide over the snow and ice. It was twelve feet long and four wide, and could therefore carry provisions, if need were, for several weeks. Fidèle Misonne soon put it in order, working upon it in the snow storehouse, whither his tools had been carried. For the first time a coal-stove was set up in this storehouse, without which all labour there would have been impossible. The pipe was carried out through one of the lateral walls, by a hole pierced in the snow; but a grave inconvenience resulted from this,— for the heat of the stove, little by little, melted the snow where it came in contact with it; and the opening visibly increased. Jean Cornbutte contrived to surround this part of the pipe with some metallic canvas, which is impermeable by heat. This succeeded completely.

While Misonne was at work upon the sledge, Penellan, aided by Marie, was preparing the clothing necessary for the expedition. Seal-skin boots they had, fortunately, in plenty. Jean Cornbutte and André Vasling occupied themselves with the provisions. They chose a small barrel of spirits-of-wine for heating a portable chafing-dish; reserves of coffee and tea in ample quantity were packed; a small box of biscuits, two hundred pounds of pemmican, and some gourds of brandy completed the stock of viands. The guns would bring down some fresh game every day. A quantity of powder was divided between several bags; the compass, sextant, and spy-glass were put carefully out of the way of injury.

On the 11th of October the sun no longer appeared above the horizon. They were obliged to keep a lighted lamp in the lodgings of the crew all the time. There was no time to lose; the explorations must be begun. For this reason: in the month of January it would become so cold that it would be impossible to venture out without peril of life. For two months at least the crew would be condemned to the most complete imprisonment; then the thaw would begin, and continue till the time when the ship should quit the ice. This thaw would, of course, prevent any explorations. On the other hand, if Louis Cornbutte and his comrades were still in existence, it was not probable that they would be able to resist the severities of the arctic winter. They must therefore be saved beforehand, or all hope would be lost. André Vasling knew all this better than any one. He therefore resolved to put every possible obstacle in the way of the expedition.

The preparations for the journey were completed about the 20th of October. It remained to select the men who should compose the party. The young girl could not be deprived of the protection of Jean Cornbutte or of Penellan; neither of these could, on the other hand, be spared from the expedition.

The question, then, was whether Marie could bear the fatigues of such a journey. She had already passed through rough experiences without seeming to suffer from them, for she was a sailor’s daughter, used from infancy to the fatigues of the sea, and even Penellan was not dismayed to see her struggling in the midst of this severe climate, against the dangers of the polar seas.

It was decided, therefore, after a long discussion, that she should go with them, and that a place should be reserved for her, at need, on the sledge, on which a little wooden hut was constructed, closed in hermetically. As for Marie, she was delighted, for she dreaded to be left alone without her two protectors.

The expedition was thus formed: Marie, Jean Cornbutte, Penellan, André Vasling, Aupic, and Fidèle Misonne were to go. Alaine Turquiette remained in charge of the brig, and Gervique and Gradlin stayed behind with him. New provisions of all kinds were carried; for Jean Cornbutte, in order to carry the exploration as far as possible, had resolved to establish depôts along the route, at each seven or eight days’ march. When the sledge was ready it was at once fitted up, and covered with a skin tent. The whole weighed some seven hundred pounds, which a pack of five dogs might easily carry over the ice.

On the 22nd of October, as the captain had foretold, a sudden change took place in the temperature. The sky cleared, the stars emitted an extraordinary light, and the moon shone above the horizon, no longer to leave the heavens for a fortnight. The thermometer descended to twenty-five degrees below zero.

The departure was fixed for the following day.

Chapter 9. The House of Snow.

On the 23rd of October, at eleven in the morning, in a fine moonlight, the caravan set out. Precautions were this time taken that the journey might be a long one, if necessary. Jean Cornbutte followed the coast, and ascended northward. The steps of the travellers made no impression on the hard ice. Jean was forced to guide himself by points which he selected at a distance; sometimes he fixed upon a hill bristling with peaks; sometimes on a vast iceberg which pressure had raised above the plain.

At the first halt, after going fifteen miles, Penellan prepared to encamp. The tent was erected against an ice-block. Marie had not suffered seriously with the extreme cold, for luckily the breeze had subsided, and was much more bearable; but the young girl had several times been obliged to descend from her sledge to avert numbness from impeding the circulation of her blood. Otherwise, her little hut, hung with skins, afforded her all the comfort possible under the circumstances.

When night, or rather sleeping-time, came, the little hut was carried under the tent, where it served as a bed-room for Marie. The evening repast was composed of fresh meat, pemmican, and hot tea. Jean Cornbutte, to avert danger of the scurvy, distributed to each of the party a few drops of lemon-juice. Then all slept under God’s protection.

After eight hours of repose, they got ready to resume their march. A substantial breakfast was provided to the men and the dogs; then they set out. The ice, exceedingly compact, enabled these animals to draw the sledge easily. The party sometimes found it difficult to keep up with them.

But the sailors soon began to suffer one discomfort — that of being dazzled. Ophthalmia betrayed itself in Aupic and Misonne. The moon’s light, striking on these vast white plains, burnt the eyesight, and gave the eyes insupportable pain.

There was thus produced a very singular effect of refraction. As they walked, when they thought they were about to put foot on a hillock, they stepped down lower, which often occasioned falls, happily so little serious that Penellan made them occasions for bantering. Still, he told them never to take a step without sounding the ground with the ferruled staff with which each was equipped.

About the 1st of November, ten days after they had set out, the caravan had gone fifty leagues to the northward. Weariness pressed heavily on all. Jean Cornbutte was painfully dazzled, and his sight sensibly changed. Aupic and Misonne had to feel their way: for their eyes, rimmed with red, seemed burnt by the white reflection. Marie had been preserved from this misfortune by remaining within her hut, to which she confined herself as much as possible. Penellan, sustained by an indomitable courage, resisted all fatigue. But it was André Vasling who bore himself best, and upon whom the cold and dazzling seemed to produce no effect. His iron frame was equal to every hardship; and he was secretly pleased to see the most robust of his companions becoming discouraged, and already foresaw the moment when they would be forced to retreat to the ship again.

On the 1st of November it became absolutely necessary to halt for a day or two. As soon as the place for the encampment had been selected, they proceeded to arrange it. It was determined to erect a house of snow, which should be supported against one of the rocks of the promontory. Misonne at once marked out the foundations, which measured fifteen feet long by five wide. Penellan, Aupic, and Misonne, by aid of their knives, cut out great blocks of ice, which they carried to the chosen spot and set up, as masons would have built stone walls. The sides of the foundation were soon raised to a height and thickness of about five feet; for the materials were abundant, and the structure was intended to be sufficiently solid to last several days. The four walls were completed in eight hours; an opening had been left on the southern side, and the canvas of the tent, placed on these four walls, fell over the opening and sheltered it. It only remained to cover the whole with large blocks, to form the roof of this temporary structure.

After three more hours of hard work, the house was done; and they all went into it, overcome with weariness and discouragement. Jean Cornbutte suffered so much that he could not walk, and André Vasling so skilfully aggravated his gloomy feelings, that he forced from him a promise not to pursue his search farther in those frightful solitudes. Penellan did not know which saint to invoke. He thought it unworthy and craven to give up his companions for reasons which had little weight, and tried to upset them; but in vain.

Meanwhile, though it had been decided to return, rest had become so necessary that for three days no preparations for departure were made.

On the 4th of November, Jean Cornbutte began to bury on a point of the coast the provisions for which there was no use. A stake indicated the place of the deposit, in the improbable event that new explorations should be made in that direction. Every day since they had set out similar deposits had been made, so that they were assured of ample sustenance on the return, without the trouble of carrying them on the sledge.

The departure was fixed for ten in the morning, on the 5th. The most profound sadness filled the little band. Marie with difficulty restrained her tears, when she saw her uncle so completely discouraged. So many useless sufferings! so much labour lost! Penellan himself became ferocious in his ill-humour; he consigned everybody to the nether regions, and did not cease to wax angry at the weakness and cowardice of his comrades, who were more timid and tired, he said, than Marie, who would have gone to the end of the world without complaint.

André Vasling could not disguise the pleasure which this decision gave him. He showed himself more attentive than ever to the young girl, to whom he even held out hopes that a new search should be made when the winter was over; knowing well that it would then be too late!

Chapter 10. Buried Alive.

The evening before the departure, just as they were about to take supper, Penellan was breaking up some empty casks for firewood, when he was suddenly suffocated by a thick smoke. At the same instant the snow-house was shaken as if by an earthquake. The party uttered a cry of terror, and Penellan hurried outside.

It was entirely dark. A frightful tempest — for it was not a thaw — was raging, whirlwinds of snow careered around, and it was so exceedingly cold that the helmsman felt his hands rapidly freezing. He was obliged to go in again, after rubbing himself violently with snow.

“It is a tempest,” said he. “May heaven grant that our house may withstand it, for, if the storm should destroy it, we should be lost!”

At the same time with the gusts of wind a noise was heard beneath the frozen soil; icebergs, broken from the promontory, dashed away noisily, and fell upon one another; the wind blew with such violence that it seemed sometimes as if the whole house moved from its foundation; phosphorescent lights, inexplicable in that latitude, flashed across the whirlwinds of the snow.

“Marie! Marie!” cried Penellan, seizing the young girl’s hands.

“We are in a bad case!” said Misonne.

“And I know not whether we shall escape,” replied Aupic.

“Let us quit this snow-house!” said André Vasling.

“Impossible!” returned Penellan. “The cold outside is terrible; perhaps we can bear it by staying here.”

“Give me the thermometer,” demanded Vasling.

Aupic handed it to him. It showed ten degrees below zero inside the house, though the fire was lighted. Vasling raised the canvas which covered the opening, and pushed it aside hastily; for he would have been lacerated by the fall of ice which the wind hurled around, and which fell in a perfect hail-storm.

“Well, Vasling,” said Penellan, “will you go out, then? You see that we are more safe here.”

“Yes,” said Jean Cornbutte; “and we must use every effort to strengthen the house in the interior.”

“But a still more terrible danger menaces us,” said Vasling.

“What?” asked Jean.

“The wind is breaking the ice against which we are propped, just as it has that of the promontory, and we shall be either driven out or buried!”

“That seems doubtful,” said Penellan, “for it is freezing hard enough to ice over all liquid surfaces. Let us see what the temperature is.”

He raised the canvas so as to pass out his arm, and with difficulty found the thermometer again, in the midst of the snow; but he at last succeeded in seizing it, and, holding the lamp to it, said,—

“Thirty-two degrees below zero! It is the coldest we have seen here yet!”

“Ten degrees more,” said Vasling, “and the mercury will freeze!”

A mournful silence followed this remark.

About eight in the morning Penellan essayed a second time to go out to judge of their situation. It was necessary to give an escape to the smoke, which the wind had several times repelled into the hut. The sailor wrapped his cloak tightly about him, made sure of his hood by fastening it to his head with a handkerchief, and raised the canvas.

The opening was entirely obstructed by a resisting snow. Penellan took his staff, and succeeded in plunging it into the compact mass; but terror froze his blood when he perceived that the end of the staff was not free, and was checked by a hard body!

“Cornbutte,” said he to the captain, who had come up to him, “we are buried under this snow!”

“What say you?” cried Jean Cornbutte.

“I say that the snow is massed and frozen around us and over us, and that we are buried alive!”

“Let us try to clear this mass of snow away,” replied the captain.

The two friends buttressed themselves against the obstacle which obstructed the opening, but they could not move it. The snow formed an iceberg more than five feet thick, and had become literally a part of the house. Jean could not suppress a cry, which awoke Misonne and Vasling. An oath burst from the latter, whose features contracted. At this moment the smoke, thicker than ever, poured into the house, for it could not find an issue.

“Malediction!” cried Misonne. “The pipe of the stove is sealed up by the ice!”

Penellan resumed his staff, and took down the pipe, after throwing snow on the embers to extinguish them, which produced such a smoke that the light of the lamp could scarcely be seen; then he tried with his staff to clear out the orifice, but he only encountered a rock of ice! A frightful end, preceded by a terrible agony, seemed to be their doom! The smoke, penetrating the throats of the unfortunate party, caused an insufferable pain, and air would soon fail them altogether!

Marie here rose, and her presence, which inspired Cornbutte with despair, imparted some courage to Penellan. He said to himself that it could not be that the poor girl was destined to so horrible a death.

“Ah!” said she, “you have made too much fire. The room is full of smoke!”

“Yes, yes,” stammered Penellan.

“It is evident,” resumed Marie, “for it is not cold, and it is long since we have felt too much heat.”

No one dared to tell her the truth.

“See, Marie,” said Penellan bluntly, “help us get breakfast ready. It is too cold to go out. Here is the chafing-dish, the spirit, and the coffee. Come, you others, a little pemmican first, as this wretched storm forbids us from hunting.”

These words stirred up his comrades.

“Let us first eat,” added Penellan, “and then we shall see about getting off.”

Penellan set the example and devoured his share of the breakfast. His comrades imitated him, and then drank a cup of boiling coffee, which somewhat restored their spirits. Then Jean Cornbutte decided energetically that they should at once set about devising means of safety.

André Vasling now said,—

“If the storm is still raging, which is probable, we must be buried ten feet under the ice, for we can hear no noise outside.”

Penellan looked at Marie, who now understood the truth, and did not tremble. The helmsman first heated, by the flame of the spirit, the iron point of his staff, and successfully introduced it into the four walls of ice, but he could find no issue in either. Cornbutte then resolved to cut out an opening in the door itself. The ice was so hard that it was difficult for the knives to make the least impression on it. The pieces which were cut off soon encumbered the hut. After working hard for two hours, they had only hollowed out a space three feet deep.

Some more rapid method, and one which was less likely to demolish the house, must be thought of; for the farther they advanced the more violent became the effort to break off the compact ice. It occurred to Penellan to make use of the chafing-dish to melt the ice in the direction they wanted. It was a hazardous method, for, if their imprisonment lasted long, the spirit, of which they had but little, would be wanting when needed to prepare the meals. Nevertheless, the idea was welcomed on all hands, and was put in execution. They first cut a hole three feet deep by one in diameter, to receive the water which would result from the melting of the ice; and it was well that they took this precaution, for the water soon dripped under the action of the flames, which Penellan moved about under the mass of ice. The opening widened little by little, but this kind of work could not be continued long, for the water, covering their clothes, penetrated to their bodies here and there. Penellan was obliged to pause in a quarter of an hour, and to withdraw the chafing-dish in order to dry himself. Misonne then took his place, and worked sturdily at the task.

In two hours, though the opening was five feet deep, the points of the staffs could not yet find an issue without.

“It is not possible,” said Jean Cornbutte, “that snow could have fallen in such abundance. It must have been gathered on this point by the wind. Perhaps we had better think of escaping in some other direction.”

“I don’t know,” replied Penellan; “but if it were only for the sake of not discouraging our comrades, we ought to continue to pierce the wall where we have begun. We must find an issue ere long.”

“Will not the spirit fail us?” asked the captain.

“I hope not. But let us, if necessary, dispense with coffee and hot drinks. Besides, that is not what most alarms me.”

“What is it, then, Penellan?”

“Our lamp is going out, for want of oil, and we are fast exhausting our provisions.— At last, thank God!”

Penellan went to replace André Vasling, who was vigorously working for the common deliverance.

“Monsieur Vasling,” said he, “I am going to take your place; but look out well, I beg of you, for every tendency of the house to fall, so that we may have time to prevent it.”

The time for rest had come, and when Penellan had added one more foot to the opening, he lay down beside his comrades.

Chapter 11. A Cloud of Smoke.

The next day, when the sailors awoke, they were surrounded by complete darkness. The lamp had gone out. Jean Cornbutte roused Penellan to ask him for the tinder-box, which was passed to him. Penellan rose to light the fire, but in getting up, his head struck against the ice ceiling. He was horrified, for on the evening before he could still stand upright. The chafing-dish being lighted up by the dim rays of the spirit, he perceived that the ceiling was a foot lower than before.

Penellan resumed work with desperation.

At this moment the young girl observed, by the light which the chafing-dish cast upon Penellan’s face, that despair and determination were struggling in his rough features for the mastery. She went to him, took his hands, and tenderly pressed them.

“She cannot, must not die thus!” he cried.

He took his chafing-dish, and once more attacked the narrow opening. He plunged in his staff, and felt no resistance. Had he reached the soft layers of the snow? He drew out his staff, and a bright ray penetrated to the house of ice!

“Here, my friends!” he shouted.

He pushed back the snow with his hands and feet, but the exterior surface was not thawed, as he had thought. With the ray of light, a violent cold entered the cabin and seized upon everything moist, to freeze it in an instant. Penellan enlarged the opening with his cutlass, and at last was able to breathe the free air. He fell on his knees to thank God, and was soon joined by Marie and his comrades.

A magnificent moon lit up the sky, but the cold was so extreme that they could not bear it. They re-entered their retreat; but Penellan first looked about him. The promontory was no longer there, and the hut was now in the midst of a vast plain of ice. Penellan thought he would go to the sledge, where the provisions were. The sledge had disappeared!

The cold forced him to return. He said nothing to his companions. It was necessary, before all, to dry their clothing, which was done with the chafing-dish. The thermometer, held for an instant in the air, descended to thirty degrees below zero.

An hour after, Vasling and Penellan resolved to venture outside. They wrapped themselves up in their still wet garments, and went out by the opening, the sides of which had become as hard as a rock.

“We have been driven towards the north-east,” said Vasling, reckoning by the stars, which shone with wonderful brilliancy.

“That would not be bad,” said Penellan, “if our sledge had come with us.”

“Is not the sledge there?” cried Vasling. “Then we are lost!”

“Let us look for it,” replied Penellan.

They went around the hut, which formed a block more than fifteen feet high. An immense quantity of snow had fallen during the whole of the storm, and the wind had massed it against the only elevation which the plain presented. The entire block had been driven by the wind, in the midst of the broken icebergs, more than twenty-five miles to the north-east, and the prisoners had suffered the same fate as their floating prison. The sledge, supported by another iceberg, had been turned another way, for no trace of it was to be seen, and the dogs must have perished amid the frightful tempest.

André Vasling and Penellan felt despair taking possession of them. They did not dare to return to their companions. They did not dare to announce this fatal news to their comrades in misfortune. They climbed upon the block of ice in which the hut was hollowed, and could perceive nothing but the white immensity which encompassed them on all sides. Already the cold was beginning to stiffen their limbs, and the damp of their garments was being transformed into icicles which hung about them.

Just as Penellan was about to descend, he looked towards André. He saw him suddenly gaze in one direction, then shudder and turn pale.

“What is the matter, Vasling?” he asked.

“Nothing,” replied the other. “Let us go down and urge the captain to leave these parts, where we ought never to have come, at once!”

Instead of obeying, Penellan ascended again, and looked in the direction which had drawn the mate’s attention. A very different effect was produced on him, for he uttered a shout of joy, and cried,—

“Blessed be God!”

A light smoke was rising in the north-east. There was no possibility of deception. It indicated the presence of human beings. Penellan’s cries of joy reached the rest below, and all were able to convince themselves with their eyes that he was not mistaken.