| News / Science News |

Last ice-covered parts of summertime Arctic Ocean vulnerable to climate change

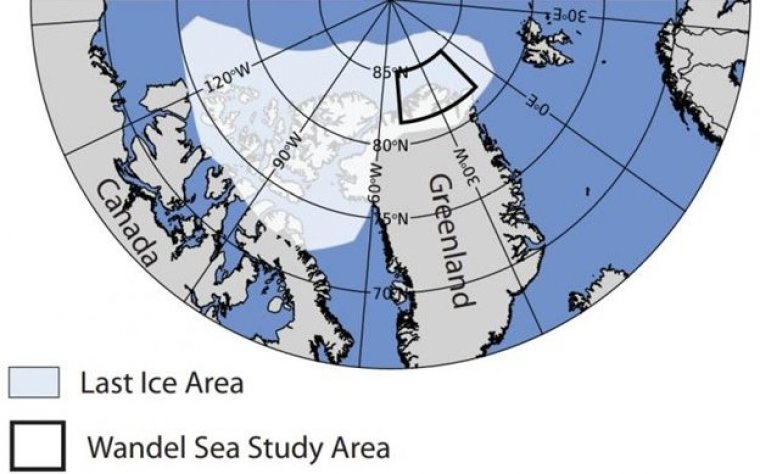

In a rapidly changing Arctic, one area might serve as a refuge -- a place that could continue to harbor ice-dependent wildlife when conditions in nearby areas become inhospitable. This region north of Greenland and the islands of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago has been termed the "Last Ice Area." Research led by the University of Washington suggests that parts of the area are already showing a decline in summer sea ice.

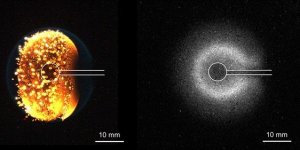

The Wandel Sea is inside what's known as the 'Last Ice Area' in the Arctic Ocean. Photo: Schweiger et al./Communications Earth & Environment

Last August, sea ice north of Greenland was vulnerable to the long-term effects of climate change, according to a new study.

"Current thinking is that this area may be the last refuge for ice-dependent species," said lead author Axel Schweiger, a polar scientist at the University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory.

How the last ice-covered regions will fare matters for polar bears that use the ice to hunt, for seals that use the ice for building dens for their young, and for walruses that use the ice as a platform for foraging.

"This area has long been expected to be the primary refuge for ice-dependent species because it is one of the last places where we expect summer sea ice to survive in the Arctic," said co-author Kristin Laidre, a scientist at the University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory.

The study focused on sea ice in August 2020 in the Wandel Sea, an area that once was covered year-round in thick, multi-year ice. Satellite images showed extensive open water and a record low of just 50% sea ice concentration on August 14, 2020.

The new study uses satellite data and sea ice models to determine what caused last summer's record low. It finds that about 80% was due to weather-related factors, like winds that break up and move the ice around. The other 20% was from the longer-term thinning of the sea ice due to global warming.

The results raise concerns about the Last Ice Area but can't immediately be applied to the entire region, Schweiger said. Also unknown is how more open water in this region would affect ice-dependent species over the short- and long-term. (National Science Foundation)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE