| News / Science News |

Marmoset study gives insights into loss of pleasure in depression

‘Anhedonia’ (the loss of pleasure) is one of the key symptoms of depression. An important component of this symptom is an inability to feel excitement in anticipation of events; however the brain mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are poorly understood.

Anhedonia is one of the key symptoms of depression. ![]()

In a study involving marmosets, scientists at the University of Cambridge have identified the region of the brain that contributes to this phenomenon, and shown that the experimental antidepressant ketamine acts on this region, helping explain why this drug may prove effective at treating anhedonia.

A key symptom of depression is anhedonia, typically defined as the loss of ability to experience pleasure. However, anhedonia also involves a lack of motivation and lack of excitement in anticipation of events.

All these aspects have proven difficult to treat. One major issue slowing down progress in developing new treatments is that the brain mechanisms that give rise to anhedonia remain largely unknown.

“Imaging studies of depressed patients have given us a clue about some of the brain regions that may be involved in anhedonia, but we still don't know which of these regions is causally responsible,” says Professor Angela Roberts from the Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience at the University of Cambridge.

“A second important issue is that anhedonia is multi-faceted – it goes beyond a loss of pleasure and can involve a lack of anticipation and motivation, and it’s possible that these different aspects may have distinct underlying causes.”

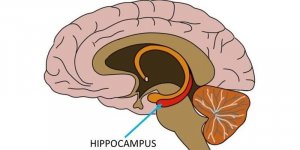

Using marmosets, a type of non-human primate, the researchers have shown how over-activity in a specific area of the brain’s frontal lobe blunts the excitement seen when anticipating a reward and the motivation to work for that reward.

By using PET scanning techniques to observe activity across the marmoset’s brain the researchers found that over-activity in a region of the brain known as ‘area 25’ had a knock-on effect to other brain regions, which also became more active, indicating that these were all part of brain circuity controlling anticipatory excitement.

The researchers investigated the effect of the experimental antidepressant, ketamine. Marmosets were given the antidepressant 24 hours ahead of the experiment. This time, even when marmosets were administered the treatment to make area 25 over-active, they still showed excitement and anticipation at the reward.

PET scanning revealed that the brain circuits were functioning normally. In other words, ketamine had blocked the effects of over-activating area 25, which would otherwise blunt anticipation.

“Understanding the brain circuits that underlie specific aspects of anhedonia is of major importance, not only because anhedonia is a core feature of depression but also because it is one of the most treatment-resistant symptoms,” says Laith Alexander, the study’s first author.

Marmosets are used to study brain disorders such as depression because of the similarity of the frontal lobes to those of humans. Rats, which are often used in psychology studies, have frontal lobes quite different to those of humans, making it less easy to translate studies of frontal lobe circuitry directly into the clinic. (University of Cambridge)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE