| Health / Health News |

Researchers develop new method to screen Alzheimer's treatment efficacy

Researchers at the University of California San Diego analyzed disease mechanisms in human neurons to determine the cause of the low success rate of drugs used in Alzheimer's treatment. The findings could result in groundbreaking treatments and improved patient outcomes, the scientists said.

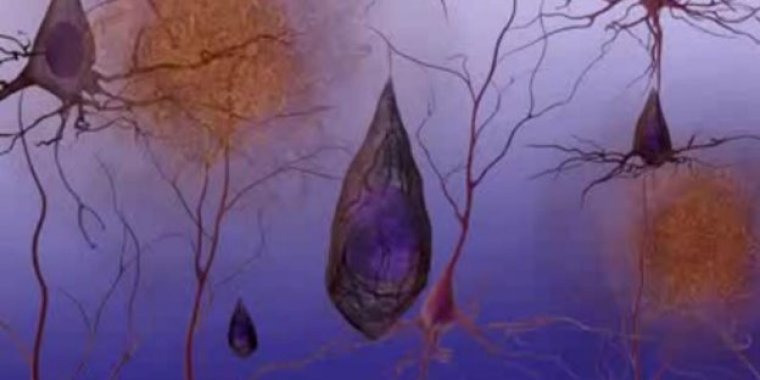

New Alzheimer's treatment screening targets lesser-known endotypes. Photo: National Institute on Aging

Current treatments for Alzheimer's were developed to target amyloid plaques, long thought to be the primary cause of neuron death and the onset of the debilitating condition.

"But this approach has not led to a cure or improved dementia in patients," said the study's senior author, Shankar Subramaniam.

Other disease mechanisms, or endotypes, are affected, including the degradation of neurons, neuron gene suppression and synaptic connection loss. The screening process examines a wider range of endotypes.

"This is a new test for measuring whether an Alzheimer's drug works,” said Subramaniam. “When drugs interact with human neurons, what endotypes do the drugs fix, and what endotypes do they not fix in the process? This method screens drugs on actual patient cells. The power of this is that you can do precision medicine and have a good model system to study Alzheimer's."

The researchers screened two experimental Alzheimer's drugs designed to reduce or prevent amyloid plaque growth and found that the drugs were only partially effective.

"Now we have a prescription for what endotypes to target during drug screening," said Subramaniam.

"What we are seeing is that fixing amyloid plaque formation does not reverse the disease. Once neurons de-differentiate into non-neurons, they lose their synaptic connections, which leads to loss of memory and cognition and as a consequence, dementia."

The researchers plan to test the drug screening method on synthetic tissue modeled after the human brain and will continue to develop potential Alzheimer's therapeutics.

"We want to take this a step further to screen drugs on more realistic tissues, not just neurons in a dish," said Subramaniam. (National Science Foundation)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE