| News / Science News |

Microbes in underground aquifers beneath deep-sea Mid-Atlantic Ridge 'chow down' on carbon

A research team led by ecologists Sunita Shah Walter of the University of Delaware and Peter Girguis of Harvard University has shown that underground aquifers near the undersea Mid-Atlantic Ridge act like natural biological reactors, pulling in cold, oxygenated seawater, and allowing microbes to consume more refractory carbon than scientists believed.

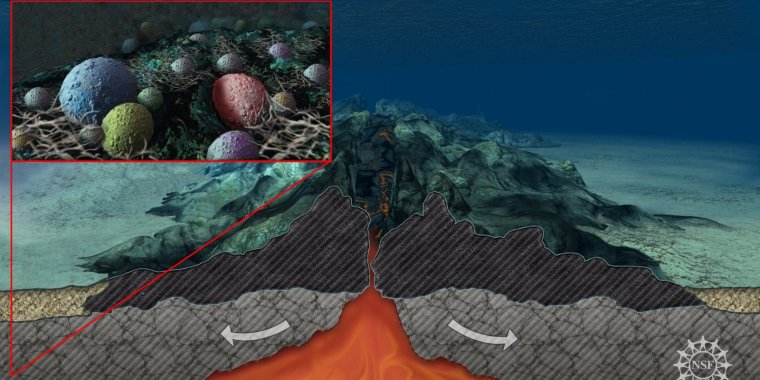

Microbes in a sub-seafloor aquifer feast on carbon in fluids flowing through the permeable rock. Image credit: National Science Foundation

In the oceans, some carbon-containing compounds, such as sugars and proteins, are quickly gobbled up by microorganisms, while others, such as the chitin found in fish scales, are much harder to consume.

Scientists have long believed that relatively little of the latter, called "refractory carbon," is degraded in the ocean. Much of it falls to the ocean floor and helps make up deep-water sediment, or so the thinking has been.

At the heart of the system is the mid-ocean ridge: undersea mountains that circle the globe.

In the deep ocean, the ridge acts like a convection cell -- water seeps into cracks and fissures on either side and is heated as it gets closer to the center.

As the heated water rises, cold, oxygenated water is pulled into the rocks, creating a massive undersea aquifer. This aquifer is a rare chance to study the ocean in its natural state.

To get those measurements, Girguis and colleagues targeted a site on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge dubbed the "North Pond." They drilled a series of wells and collected water samples to identify which microbes call the aquifer home and whether they're capable of consuming carbon.

"We wanted to collect pristine water and microbial samples," Girguis said. "When you look at the mid-ocean ridge and think about the water that's circulating through it, it looks as though a lot of the ocean is moving through this cold environment. We wanted to know what's going on there with the microbes and what's happening with the carbon they get."

"We have been able to show that water comes in with a certain oxygen concentration, and as it drops, the carbon goes down in direct proportion," he said. "That gives us a high degree of confidence that microbes are eating it."

A little more than 50 percent of the carbon there is being consumed. A majority of the carbon is being degraded in these aquifers, especially since the entire ocean circulates through them every few tens of thousands of years. That's fast on ocean timescales. (National Science Foundation)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE