| News / Space News |

Mini-Neptune in Double Star System is a Planetary Puzzle

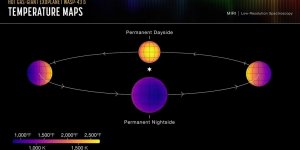

A planet that could resemble a smaller version of our own Neptune orbits one of two Sun-like stars that also orbit each other. The planet dwells in the “habitable zone,” with a potentially moderate temperature, and poses a challenge to prevailing ideas of planet formation.

Artist's concept of planet TOI 4633 c in its double-star system. Photo: Ed Bell for Simons Foundation

Astronomers once imagined that our solar system – with its middle-aged, quiet Sun hosting small, rocky planets in closer orbits and gas giants farther out – might be typical, even run-of-the-mill. But so far, in an era of increasingly powerful planet-hunting technology, it’s turning out to be anything but.

Other planetary systems can look very different, if not downright weird (or are we the weird ones?).

A system called TOI 4633 seems truly strange: a mysterious type of planet known as a “mini-Neptune” traces an Earth-like, 272-day orbit around one of two stars locked in their own orbital embrace.

But the stellar orbits, and those of the mini-Neptune and a possible sibling planet, are raising questions about how planetary systems form – and whether such arrangements can remain stable over time.

Among the thousands of exoplanets – planets beyond our solar system – confirmed in our galaxy so far, most were detected using the “transit” method: measuring the tiny dip in starlight as a planet crosses the face of its star.

And most of these transit detections involve planets with short orbits, their “years” – once around the star – lasting a few days or weeks.

So the detection of planet TOI 4633 c was a welcome departure. That isn’t only because its 272-day orbit places it in fairly exclusive company: 175 transiting planets found so far with years longer than 100 days, and only 40 over 250 days.

The planet, detected using TESS (the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite), also orbits in the habitable zone, the distance from a star that could allow liquid water to form on a planetary surface.

For planet c, of course, that’s almost certainly not the case; it most likely has a large, dense atmosphere, perhaps similar to Neptune’s, that would rule out surface water.

A moon might be one way around this. The longer a planet’s orbital period, the more likely it is to host a satellite, so it isn’t difficult to imagine a potentially habitable moon, à la the fictional Pandora.

The brightness of this system could make it a likely target in the continuing search for such “exomoons.”

The list of puzzling properties for this system continues. Measurements using a second detection method revealed a possible sibling planet with a 34-day orbit. This one does not, from Earth’s perspective, cross the face of its star, so its potential presence was revealed by “radial velocity.”

The light coming from a star shifts slightly to and fro as the gravity of an orbiting planet tugs it one way, then another; follow-up investigations will be needed to confirm that the sibling planet, suggested by radial velocity measurements, is really there.

Further investigation of this system also could prove important for understanding binary star systems, or pairs of stars that orbit each other. A companion star in this case orbits the primary star in just 230 years, allowing them to approach each other closely by interstellar standards.

The stars’ oval-shaped mutual orbit and close approach, along with a transiting planet on a long orbit around one of the stars, make this a standout system – one that will allow scientists to test their ideas about how planetary systems form and whether such unusual orbital configurations can manage to keep themselves stable over billions of years.

Planet TOI 4633 c was discovered by 15 “citizen scientists” who pored over TESS data as part of the Planet Hunters TESS citizen science project.

Some 40,000 such volunteers regularly inspect “light curves” – lines that trace the amount of light coming from a star and that dip downward during a planet crossing, then curve back up when the crossing is finished.

Scientists investigating the system also got an assist from more than a century ago: archival data that was part of the Washington Double Star Catalog, maintained by the U.S. Naval Observatory, and was gathered between 1905 and 2011.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE