| Health / Health News |

Monoclonal antibody prevents malaria

One dose of a new monoclonal antibody discovered and developed at the National Institutes of Health safely prevented malaria for up to nine months in people who were exposed to the malaria parasite.

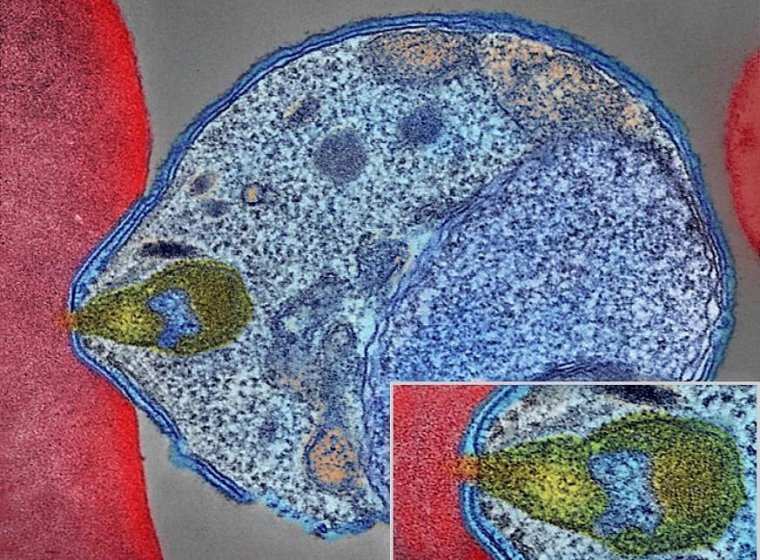

Colorized electron micrograph showing malaria parasite (right, blue) attaching to a human red blood cell. The inset shows a detail of the attachment point at higher magnification. Photo: NIAID

So far, no licensed or experimental malaria vaccine that has completed Phase 3 testing provides more than 50% protection from the disease over the course of a year or longer.

Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites, which are transmitted to people through the bite of an infected mosquito. The mosquito injects the parasites in a form called sporozoites into the skin and bloodstream. These travel to the liver, where they mature and multiply.

Then the mature parasite spreads throughout the body via the bloodstream to cause illness. P. falciparum is the Plasmodium species most likely to result in severe malaria infections, which, if not promptly treated, may lead to death.

Laboratory and animal studies have demonstrated that antibodies can prevent malaria by neutralizing the sporozoites of P. falciparum in the skin and blood before they can infect liver cells.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) trial tested whether a neutralizing monoclonal antibody called CIS43LS could safely provide a high level of protection from malaria in adults following careful, voluntary, laboratory-based exposure to infected mosquitos in the United States.

CIS43LS was derived from a naturally occurring neutralizing antibody called CIS43. Researchers led by Robert A. Seder, M.D., chief of the Cellular Immunology Section of the VRC Immunology Laboratory, isolated CIS43 from the blood of a volunteer who had received an investigational malaria vaccine.

The scientists found that CIS43 binds to a unique site on a parasite surface protein that is important for facilitating malaria infection and is the same on all variants of P. falciparum sporozoites worldwide.

The researchers subsequently modified this antibody to extend the amount of time it would remain in the bloodstream, creating CIS43LS.

After animal studies of CIS43LS for malaria prevention yielded promising results, VRC investigators launched a Phase 1 clinical trial of the experimental antibody with 40 healthy adults ages 18 to 50 years who had never had malaria or been vaccinated for the disease.

The trial was led by Martin Gaudinski, M.D., medical director of the VRC Clinical Trials Program, and was conducted at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) in Silver Spring, Maryland.

During the first half of the trial, the study team gave 21 participants one dose of CIS43LS by either an intravenous infusion or an injection under the skin.

The infusions ranged from 5 to 40 milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg) of body weight, and the subcutaneous injections were 5 mg/kg.

Investigators followed the participants for 6 months to learn whether the infusions and subcutaneous injections of the various doses of the experimental antibody were safe and well tolerated.

In addition, they measured the amount of CIS43LS in the blood to determine its durability over time.

In the second half of the trial, six participants who had received an intravenous infusion during the first half of the trial continued to participate. Four of these participants received a second antibody infusion while the other two did not.

In addition, four new participants joined the study and received a single intravenous infusion of CIS43LS. Another seven people joined the study as controls who did not receive the antibody.

All participants in the second half of the trial provided informed consent to be exposed to the malaria parasite in what is known as a controlled human malaria infection (CHMI).

In this procedure, volunteers are exposed to P. falciparum through bites of infected mosquitos in a carefully controlled setting, then are closely monitored by medical staff for several weeks and promptly treated if they develop malaria.

All participants in the second half of the trial provided informed consent to be exposed to the malaria parasite in what is known as a controlled human malaria infection (CHMI).

In this procedure, volunteers are exposed to P. falciparum through bites of infected mosquitos in a carefully controlled setting, then are closely monitored by medical staff for several weeks and promptly treated if they develop malaria.

CHMI has been used for decades to generate information about the safety and protective effect of malaria vaccine candidates and potential antimalarial drugs.

Nine participants who had received CIS43LS and six participants who served as controls voluntarily underwent CHMI and were closely monitored for 21 days. Within that period, none of the nine participants who had received CIS43LS developed malaria, but five of the six controls did.

The participants with malaria received standard therapy to eliminate the infection.

Among the nine participants who received CIS43LS and were protected, seven underwent CHMI approximately 4 weeks after their infusion. The other two participants had received their sole infusion during the first half of the study and were infected approximately 9 months later.

These results indicate that just one dose of the experimental antibody can prevent malaria for 1 to 9 months after infusion. Collectively, these data provide the first evidence that administration of an anti-malaria monoclonal antibody is safe and can prevent malaria infection in humans. (National Institutes of Health)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE