| News / Space News |

Cassini Reveals Surprises with Titan's Lakes

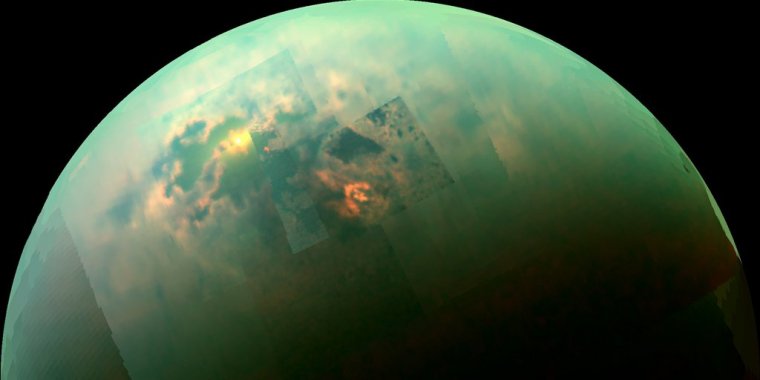

On its final flyby of Saturn's largest moon in 2017, NASA's Cassini spacecraft gathered radar data revealing that the small liquid lakes in Titan's northern hemisphere are surprisingly deep, perched atop hills and filled with methane.

This near-infrared, color view from Cassini shows the sun glinting off of Titan's north polar seas. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. Arizona/Univ. Idaho

The new findings are the first confirmation of just how deep some of Titan's lakes are (more than 300 feet, or 100 meters) and of their composition. They provide new information about the way liquid methane rains on, evaporates from and seeps into Titan - the only planetary body in our solar system other than Earth known to have stable liquid on its surface.

Scientists have known that Titan's hydrologic cycle works similarly to Earth's - with one major difference. Instead of water evaporating from seas, forming clouds and rain, Titan does it all with methane and ethane. We tend to think of these hydrocarbons as a gas on Earth, unless they're pressurized in a tank. But Titan is so cold that they behave as liquids, like gasoline at room temperature on our planet.

Scientists have known that the much larger northern seas are filled with methane, but finding the smaller northern lakes filled mostly with methane was a surprise. Previously, Cassini data measured Ontario Lacus, the only major lake in Titan's southern hemisphere. There they found a roughly equal mix of methane and ethane. Ethane is slightly heavier than methane, with more carbon and hydrogen atoms in its makeup.

Adding to the oddities of Titan, with its Earth-like features carved by exotic materials, is the fact that the hydrology on one side of the northern hemisphere is completely different than the that of other side.

On the eastern side of Titan, there are big seas with low elevation, canyons and islands. On the western side: small lakes. And the new measurements show the lakes perched atop big hills and plateaus.

The new radar measurements confirm earlier findings that the lakes are far above sea level, but they conjure a new image of landforms - like mesas or buttes - sticking hundreds of feet above the surrounding landscape, with deep liquid lakes on top.

The fact that these western lakes are small - just tens of miles across - but very deep also tells scientists something new about their geology: It's the best evidence yet that they likely formed when the surrounding bedrock of ice and solid organics chemically dissolved and collapsed. On Earth, similar water lakes are known as karstic lakes.

There was some seasonally driven change in the surface liquids. One possibility is that these transient features could have been shallower bodies of liquid that over the course of the season evaporated and infiltrated into the subsurface.

These results and the findings from the Nature Astronomy paper on Titan's deep lakes support the idea that hydrocarbon rain feeds the lakes, which then can evaporate back into the atmosphere or drain into the subsurface, leaving reservoirs of liquid stored below. (NASA)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE