| News / Space News |

NASA’s Juno Exploring Jovian Moons During Extended Mission

NASA’s Juno mission is scheduled to obtain images of the Jovian moon Io on Dec. 15 as part of its continuing exploration of Jupiter’s inner moons. Now in the second year of its extended mission to investigate the interior of Jupiter, the solar-powered spacecraft performed a close flyby of Ganymede in 2021 and of Europa earlier this year.

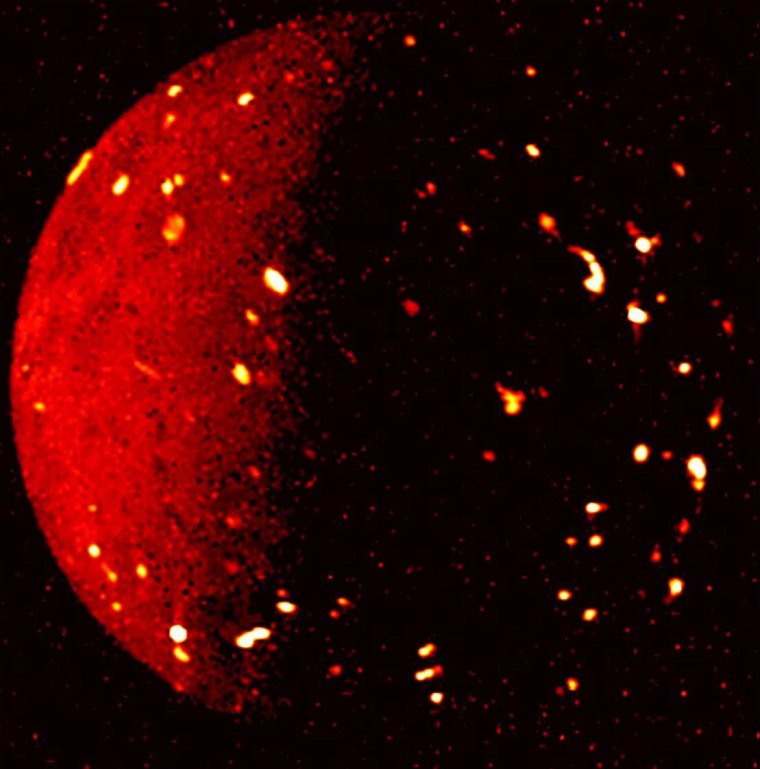

NASA’s Juno mission captured this infrared view of Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io on July 5, 2022, when the spacecraft was about 50,000 miles (80,000 kilometers) away. This infrared image was derived from data collected by the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument aboard Juno. In this image, the brighter the color the higher the temperature recorded by JIRAM. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM

“The team is really excited to have Juno’s extended mission include the study of Jupiter’s moons. With each close flyby, we have been able to obtain a wealth of new information,” said Juno Principal Investigator Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio.

“Juno sensors are designed to study Jupiter, but we’ve been thrilled at how well they can perform double duty by observing Jupiter’s moons.”

Several papers based on the June 7, 2021, Ganymede flyby were recently published in the Journal of Geophysical Research and Geophysical Research Letters.

They include findings on the moon’s interior, surface composition, and ionosphere, along with its interaction with Jupiter’s magnetosphere, from data obtained during the flyby.

Preliminary results from Juno’s Sept. 9 flyby of Europa include the first 3D observations of Europa’s ice shell.

During the flybys, Juno’s Microwave Radiometer (MWR) added a third dimension to the mission’s Jovian moon exploration: It provided a groundbreaking look beneath the water-ice crust of Ganymede and Europa to obtain data on its structure, purity, and temperature down to as deep as about 15 miles (24 kilometers) below the surface.

Visible-light imagery obtained by the spacecraft’s JunoCam, as well as by previous missions to Jupiter, indicates Ganymede’s surface is characterized by a mixture of older dark terrain, younger bright terrain, and bright craters, as well as linear features that are potentially associated with tectonic activity.

“When we combined the MWR data with the surface images, we found the differences between these various terrain types are not just skin deep,” said Bolton.

“Young, bright terrain appears colder than dark terrain, with the coldest region sampled being the city-sized impact crater Tros. Initial analysis by the science team suggests Ganymede’s conductive ice shell may have an average thickness of approximately 30 miles or more, with the possibility that the ice may be significantly thicker in certain regions.”

During the spacecraft’s June 2021 close approach to Ganymede, Juno’s Magnetic Field (MAG) and Jovian Auroral Distributions Experiment (JADE) instruments recorded data showing evidence of the breaking and reforming of magnetic field connections between Jupiter and Ganymede.

Juno’s ultraviolet spectrograph (UVS) has been observing similar events with the moon’s ultraviolet auroral emissions, organized into two ovals that wrap around Ganymede.

Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanic place in the solar system, will remain an object of the Juno team’s attention for the next year and a half.

Their Dec. 15 exploration of the moon will be the first of nine flybys – two of them from just 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) away. Juno scientists will use those flybys to perform the first high-resolution monitoring campaign on the magma-encrusted moon, studying Io’s volcanoes and how volcanic eruptions interact with Jupiter’s powerful magnetosphere and aurora. (NASA)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE