| News / Space News |

NASA’s Juno Gets a Close-Up Look at Lava Lakes on Jupiter’s Moon Io

Infrared imagery from the solar-powered spacecraft heats up the discussion on the inner workings of Jupiter’s hottest moon.

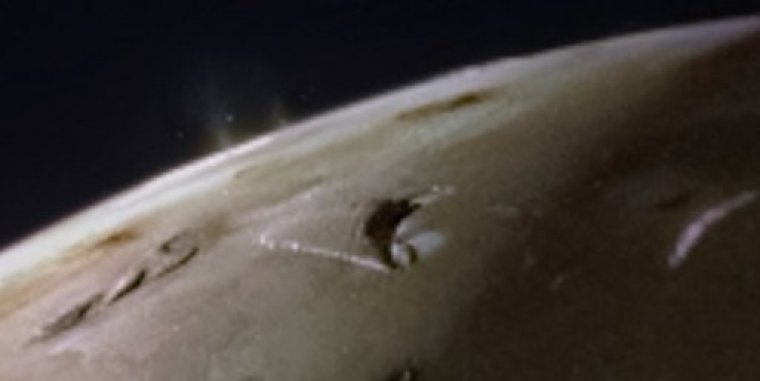

The JunoCam instrument aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft captured two volcanic plumes rising above the horizon of Jupiter’s moon Io. The image was taken Feb. 3 from a distance of about 2,400 miles (3,800 kilometers). Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS Image processing by Andrea Luck

New findings from NASA’s Juno probe provide a fuller picture of how widespread the lava lakes are on Jupiter’s moon Io and include first-time insights into the volcanic processes at work there.

These results come courtesy of Juno’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument, contributed by the Italian Space Agency, which “sees” in infrared light.

Io has intrigued the astronomers since 1610, when Galileo Galilei first discovered the Jovian moon, which is slightly larger than Earth's Moon. Some 369 years later, NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft captured a volcanic eruption on the moon.

Subsequent missions to Jupiter, with more Io flybys, discovered additional plumes — along with lava lakes.

Scientists now believe Io, which is stretched and squeezed like an accordion by neighboring moons and massive Jupiter itself, is the most volcanically active world in the solar system.

But while there are many theories on the types of volcanic eruptions across the surface of the moon, little supporting data exists.

In both May and October 2023, Juno flew by Io, coming within about 21,700 miles (35,000 kilometers) and 8,100 miles (13,000 kilometers), respectively. Among Juno’s instruments getting a good look at the beguiling moon was JIRAM.

Designed to capture the infrared light (which is not visible to the human eye) emerging from deep inside Jupiter, JIRAM probes the weather layer down to 30 to 45 miles (50 to 70 kilometers) below the gas giant’s cloud tops. But during Juno’s extended mission, the mission team has also used the instrument to study the moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

The JIRAM Io imagery showed the presence of bright rings surrounding the floors of numerous hot spots.

“The high spatial resolution of JIRAM’s infrared images, combined with the favorable position of Juno during the flybys, revealed that the whole surface of Io is covered by lava lakes contained in caldera-like features,” said Alessandro Mura, a Juno co-investigator from the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome.

“In the region of Io’s surface in which we have the most complete data, we estimate about 3% of it is covered by one of these molten lava lakes.” (A caldera is a large depression formed when a volcano erupts and collapses.)

JIRAM’s Io flyby data not only highlights the moon’s abundant lava reserves, but also provides a glimpse of what may be going on below the surface. Infrared images of several Io lava lakes show a thin circle of lava at the border, between the central crust that covers most of the lava lake and the lake’s walls.

Recycling of melt is implied by the lack of lava flows on and beyond the rim of the lake, indicating that there is a balance between melt that has erupted into the lava lakes and melt that is circulated back into the subsurface system.

“We now have an idea of what is the most frequent type of volcanism on Io: enormous lakes of lava where magma goes up and down,” said Mura.

“The lava crust is forced to break against the walls of the lake, forming the typical lava ring seen in Hawaiian lava lakes. The walls are likely hundreds of meters high, which explains why magma is generally not observed spilling out of the paterae” — bowl-shaped features created by volcanism — “and moving across the moon’s surface.”

JIRAM data suggests that most of the surface of these Io hot spots is composed of a rocky crust that moves up and down cyclically as one contiguous surface due to the central upwelling of magma.

In this hypothesis, because the crust touches the lake’s walls, friction keeps it from sliding, causing it to deform and eventually break, exposing lava just below the surface.

An alternative hypothesis remains in play: Magma is welling up in the middle of the lake, spreading out and forming a crust that sinks along the rim of the lake, exposing lava.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE