| News / Space News |

NASA Releases Kepler Survey Catalog with Hundreds of New Planet Candidates

NASA’s Kepler space telescope team has released a mission catalog of planet candidates that introduces 219 new planet candidates, 10 of which are near-Earth size and orbiting in their star's habitable zone, which is the range of distance from a star where liquid water could pool on the surface of a rocky planet.

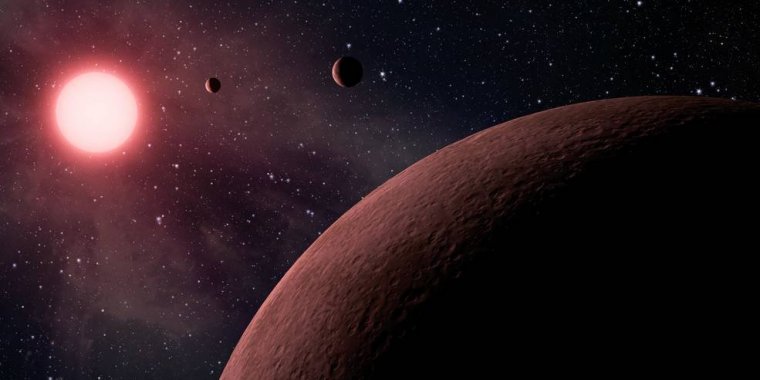

NASA’s Kepler space telescope team has identified 219 new planet candidates. ![]()

With the release of this catalog, derived from data publicly available on the NASA Exoplanet Archive, there are now 4,034 planet candidates identified by Kepler. Of which, 2,335 have been verified as exoplanets. Of roughly 50 near-Earth size habitable zone candidates detected by Kepler, more than 30 have been verified.

Additionally, results using Kepler data suggest two distinct size groupings of small planets. Both results have significant implications for the search for life.

The final Kepler catalog will serve as the foundation for more study to determine the prevalence and demographics of planets in the galaxy, while the discovery of the two distinct planetary populations shows that about half the planets we know of in the galaxy either have no surface, or lie beneath a deep, crushing atmosphere – an environment unlikely to host life.

The Kepler space telescope hunts for planets by detecting the minuscule drop in a star’s brightness that occurs when a planet crosses in front of it, called a transit.

To ensure a lot of planets weren't missed, the team introduced their own simulated planet transit signals into the data set and determined how many were correctly identified as planets. Then, they added data that appear to come from a planet, but were actually false signals, and checked how often the analysis mistook these for planet candidates.

This work told them which types of planets were overcounted and which were undercounted by the Kepler team’s data processing methods.

The team found a clean division in the sizes of rocky, Earth-size planets and gaseous planets smaller than Neptune. Few planets were found between those groupings.

It seems that nature commonly makes rocky planets up to about 75 percent bigger than Earth. For reasons scientists don't yet understand, about half of those planets take on a small amount of hydrogen and helium that dramatically swells their size, allowing them to "jump the gap" and join the population closer to Neptune’s size. (NASA)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE