| Health / Health News |

New 3D model shows how cadmium exposure may affect heart development

Researchers have developed a three-dimensional model that shows how exposure to cadmium might lead to congenital heart disease. Affecting nearly 40,000 newborns a year, congenital heart disease is the most common type of birth defect in the United States. The model was created by scientists at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), part of the National Institutes of Health.

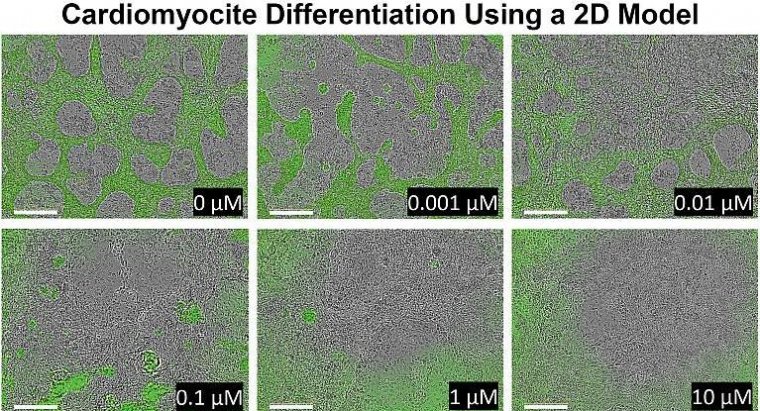

2D model showing how the pluripotent stem cells react to human relevant doses of cadmium over 8 days. From the control in the first panel, to the last panel, researchers can see how the differentiation to cardiomyocytes is inhibited with different doses of cadmium. Photo: NIEHS

Cadmium is a metal that can be released into the environment through mining and various industrial processes, and it has been found in air, soil, water, and tobacco.

The metal can enter the food chain when plants absorb it from soil. Previous studies suggested that maternal exposure to cadmium might be a significant risk factor for congenital heart disease.

Using models derived from human cells and tissues, called in vitro models, researchers designed a 3D organoid model that mimics how the human heart develops.

The researchers saw how exposure to low levels of cadmium can block usual formation of cardiomyocytes, which are the major type of cells that form the heart. In doing so, they revealed the biological mechanisms that might explain how cadmium could induce heart abnormalities.

“The models we created are useful for not only studying cadmium, but for studying other chemicals and substances as well,” said study lead Erik Tokar, Ph.D., from the Mechanistic Toxicology Branch of the NIEHS Division of Translational Toxicology (DTT).

For the study, the researchers developed three different models to evaluate the effects of cadmium on different stages of heart development.

First, they used human pluripotent stem cells to develop 3D embryoid bodies to mimic early steps in tissue and organ formation in humans.

They then used a 2D in vitro model that included a fluorescent regulatory protein system (NKX2-5) known to be involved in heart development, which allowed them to look at cadmium toxicity after exposure.

The 3D cardiac organoid model, which can simulate the beating heart, confirmed what was seen in the other two models, showing how low doses of cadmium can inhibit the cardiomyocytes from functioning properly.

The study builds on decades of work by toxicology researchers to advance knowledge about how environmental exposures may contribute to human diseases including cancer, cardiovascular disease, autism, and other conditions.

“These new models are leveraging advances in technology that allow us to model human biology in a way that identifies real human health hazards,” noted Brian Berridge, D.V.M., Ph.D., scientific director, DTT. “They also help reduce our reliance on animal testing.”

“We found that early exposure to human-relevant levels of cadmium lead to a dramatic inhibitory effect on cardiomyocyte differentiation, whereas later stage exposures did not have this effect,” said Xian Wu, Ph.D., who conducted these studies.

“This cadmium exposure also damaged the cardiac organoid functionality.” (National Institutes of Health)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE