| Health / Health News |

New Hope for Stopping An Understudied Heart Disease in Its Tracks

Thanks, in part, to pigs at the University of Wisconsin-Madison's Arlington Agricultural Research Station, scientists now are catching up on understanding the roots of calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD).

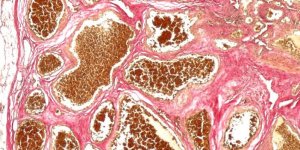

Aortic Valve Regurgitation vs. Aortic Valve Stenosis. ![]()

For a long time, people thought CAVD was just the valvular equivalent of atherosclerosis. But valve cells are quite unique and distinct from the smooth muscle cells in our blood vessels, which explains why some treatments for atherosclerosis, such as statins, don't work for CAVD.

The researchers teased apart, for the first time, the early cascade of events that may eventually cause stenosis, a severe narrowing of the aortic valve that reduces blood flow to body tissues and weakens the heart.

The only current treatment for stenosis is valve replacement, which typically requires risky and expensive open-heart surgery.

Since the hearts of mice and other small animals are vastly different from the human organ, CAVD research has long been hampered by a lack of good animal models. That's why the pigs -- specifically those bred to have an overdose of fatty molecules in their arteries -- were an important starting point for the current study.

Their valves provided a snapshot of early CAVD that is challenging to capture in humans, showing that it typically begins with the accumulation of certain sugar molecules called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in valve tissue. But to examine exactly how this tissue responds to increasing levels of GAGs, the researchers needed a greater amount of valve tissue than living pigs could provide.

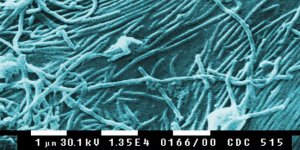

That prompted them to create a first-of-its-kind platform mimicking hallmarks of early porcine CAVD in a lab dish. Key for this model was the ability to grow valve cells in their native healthy form, an important distinction from many previous studies that had focused on already diseased cells.

When the researchers changed only the amount of GAGs these native valve cells were exposed to, while keeping all other conditions the same, they observed surprising results that challenged previous assumptions.

They noticed two distinct effects: GAGs directly increased a chemical needed to grow new blood vessels, and also trapped low-density lipoprotein (LDL) molecules.

Neither of these effects was immediately detrimental for valve cells, but the trapping made it more likely for oxygen to react with LDL molecules, and the accumulation of oxidized LDL appeared to be a bottleneck event for a multi-stage process toward valve cell damage.

This multi-stage process may explain why 25 percent of adults over the age of 65 have CAVD with partially blocked aortic valves, but only one percent goes on to develop stenosis due to a valve that can no longer open and close properly.

The fact that native valve cells cannot oxidize LDL themselves, while smooth muscle cells in blood vessels can, also highlights a key distinction between CAVD and atherosclerosis.

The study has important implications for the development of new drugs that may prevent early CAVD from progressing to stenosis by making GAGs less likely to bind LDL. (Tasnim News Agency)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE