| Science |

New Microbial Species Discovered in Harsh Lake Offers Clues to Complex Life's Origins

Scientists have discovered a new species of tiny microbes in an extremely inhospitable lake, which form large colonies and interact with other microbes in unique ways.

New Microbial Species Discovered in Harsh Lake Offers Clues to Complex Life's Origins. Image credit: tasnimnews.com

This discovery may provide insights into the evolution of complex life forms.

A team of researchers from the United States, United Kingdom, and Spain has identified a new species named Barroeca monosierra in an environment with extreme salinity.

The microbe belongs to the group known as choanoflagellates, single-celled organisms that can cluster together to form colonies resembling multicellular life.

B. monosierra was discovered thriving in Mono Lake, a highly salty environment almost three times saltier than the Pacific Ocean.

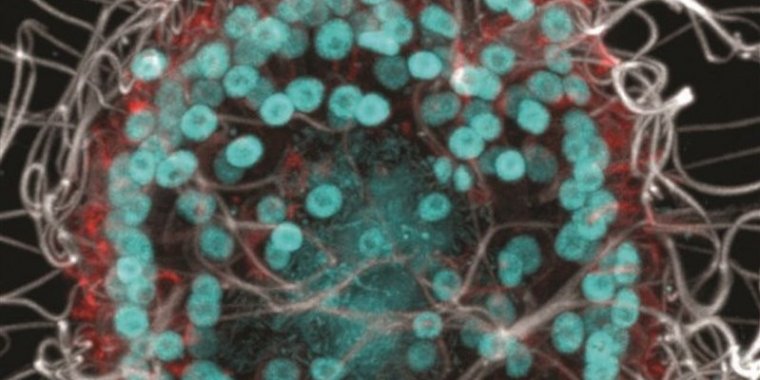

The species forms colonies of up to 100 cells, significantly larger than those of related species.

What makes this discovery even more intriguing is that the centers of these colonies house smaller communities of live bacteria, making B. monosierra one of the simplest organisms known to have its own microbiome.

Researchers speculate that the microbes might be using these bacteria for protection from the toxic lake water or possibly farming them for future consumption.

Choanoflagellates are considered the closest living relatives of animals, making them of particular interest to biologists studying the evolution of multicellular organisms.

Nicole King, a cell biologist from the University of California, Berkeley, noted that the colonies formed by B. monosierra resemble the blastula, a hollow ball of cells that appears early in animal development.

"We wanted to learn more about it," King said.

Mono Lake is known for its extreme conditions, with high concentrations of chlorides, carbonates, and sulfates accumulated over 80,000 years.

The harsh environment supports few forms of life, primarily alkali flies, brine shrimp, and some tiny worms.

However, a close examination of water samples from Mono Lake led to the discovery of B. monosierra.

"It was just packed full of these big, beautiful colonies of choanoflagellates," King said. "They were the biggest ones we'd ever seen."

These single-celled organisms have long tails, known as flagella, that help them move. In colonies, the flagella work together to propel the entire group.

In contrast to other choano colonies, where cell heads meet in the center, the B. monosierra colonies have hollow centers with cells connected by an extracellular matrix.

The team used DNA staining to reveal not only the donut-shaped chromosomes of the choano cells but also a surprising cloud of DNA in the colony's center.

RNA probes confirmed the presence of live bacteria within these centers, suggesting a selective relationship between the choanos and the bacteria.

Further experiments showed that only certain types of bacteria found in Mono Lake were present inside the colonies.

Latex microspheres were introduced in another experiment, which demonstrated that the bacteria were actively entering the colonies rather than just drifting in.

"No one had ever described a choanoflagellate with a stable physical interaction with bacteria," King said.

"In our prior studies, we found that choanos responded to small bacterial molecules floating through the water or were eating the bacteria, but there was no evidence of a potential symbiotic relationship. Or in this case, a microbiome."

The researchers plan to use B. monosierra to study the interactions between bacteria and more complex organisms, potentially shedding light on how life transitioned from single-celled to multicellular forms. (Tasnim News Agency)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE