| News / Space News |

New Study Shows What Interstellar Visitor ‘Oumuamua Can Teach Us

The first interstellar object ever seen in our solar system, named ‘Oumuamua, is giving scientists a fresh perspective on the development of planetary systems. A new study calculated how this visitor from outside our solar system fits into what we know about how planets, asteroids and comets form.

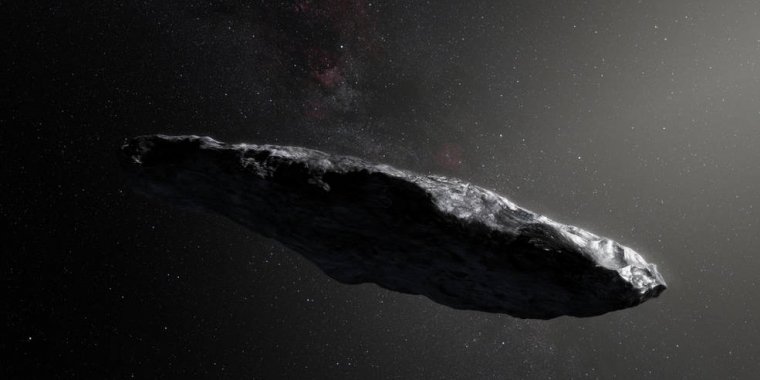

An illustration of ‘Oumuamua, the first object we’ve ever seen pass through our own solar system that has interstellar origins. Image credits: European Southern Observatory/M. Kornmesser

On Oct. 19, 2017, astronomers confirmed it was the first object of interstellar origin that we’ve seen. The team dubbed it ‘Oumuamua (pronounced oh-MOO-ah-MOO-ah), which means “a messenger from afar arriving first” in Hawaiian — and it’s already living up to its name.

On Sept. 19, ‘Oumuamua sped past the Sun at about 196,000 mph (315,400 km/h), fast enough to escape the Sun’s gravitational pull and break free of the solar system, never to return. Usually, an object traveling at a similar speed would be a comet falling sunward from the outer solar system.

Comets are icy objects that range between house-sized to many miles across. But they usually shed gas and dust as they approach the Sun and warm up. ‘Oumuamua didn’t. Some scientists interpreted this to mean that ‘Oumuamua was a dry asteroid.

Planets and planetesimals, smaller objects that include comets and asteroids, condense out of disks of dust, gas and ice around young stars. Smaller objects that form closer to their stars are too hot to have stable surface ice and become asteroids. Those that form farther away use ice as a building block and become comets. The region where asteroids develop is relatively small.

Scientists suspect most ejected planetesimals come from systems with giant gas planets. The gravitational pull of these massive planets can fling objects out of their system and into interstellar space. Systems with giant planets in unstable orbits are the most efficient at ejecting these smaller bodies because as the giants shift around, they come into contact with more material. Systems that do not form giant planets rarely eject material.

Using simulations from previous research, they showed that a small percentage of objects get so close to gas giants as they’re ejected that they should be torn into pieces. The researchers believe the strong gravitational stretching that occurs in these scenarios could explain ‘Oumuamua’s long, thin cigar-like shape. (NASA)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE