| News / Science News |

Potential Plumes on Europa Could Come From Water in the Crust

Plumes of water vapor that may be venting into space from Jupiter's moon Europa could come from within the icy crust itself, according to new research. A model outlines a process for brine, or salt-enriched water, moving around within the moon's shell and eventually forming pockets of water - even more concentrated with salt - that could erupt.

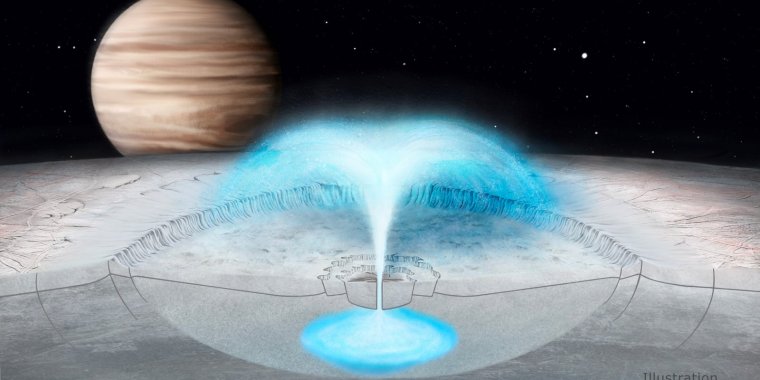

This illustration of Jupiter's icy moon Europa depicts a cryovolcanic eruption in which brine from within the icy shell could blast into space. A new model proposing this process may also shed light on plumes on other icy bodies. Image credit: Justice Wainwright

Europa scientists have considered the possible plumes on Europa a promising way to investigate the habitability of Jupiter's icy moon, especially since they offer the opportunity to be directly sampled by spacecraft flying through them.

The insights into the activity and composition of the ice shell covering Europa's global, interior ocean can help determine if the ocean contains the ingredients needed to support life.

This new work that offers an additional scenario for some plumes proposes that they may originate from pockets of water embedded in the icy shell rather than water forced upward from the ocean below.

The source of the plumes is important: Water originating from the icy crust is considered less hospitable to life than the global interior ocean because it likely lacks the energy that is a necessary ingredient for life. In Europa's ocean, that energy could come from hydrothermal vents on the sea floor.

"Understanding where these water plumes are coming from is very important for knowing whether future Europa explorers could have a chance to actually detect life from space without probing Europa's ocean," said lead author Gregor Steinbrügge, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences.

Using images collected by NASA's Galileo spacecraft, the researchers developed a model to propose how a combination of freezing and pressurization could lead to a cryovolcanic eruption, or a burst of frigid water.

The researchers focused their analyses on Manannán, an 18-mile-wide (29-kilometer-wide) crater on Europa that resulted from an impact with another celestial object tens of millions of years ago.

Reasoning that such a collision would have generated tremendous heat, they modeled how the melted ice and subsequent freezing of the water pocket within the icy shell could have pressurized it and caused the water to erupt.

"The comet or asteroid hitting the ice shell was basically a big experiment which we're using to construct hypotheses to test," said co-author Don Blankenship, senior research scientist at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) and principal investigator of the radar instrument, REASON (Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface). "Our model makes specific predictions we can test using data from the radar and other instruments on Europa Clipper."

The model indicates that as Europa's water partially froze into ice following the impact, leftover pockets of water could have been created in the moon's surface. These salty water pockets can move sideways through Europa's ice shell by melting adjacent regions of ice and consequently become even saltier in the process.

The model proposes that when a migrating brine pocket reached the center of Manannán Crater, it became stuck and began freezing, generating pressure that eventually resulted in a plume, estimated to have been over a mile high (1.6 kilometers).

The eruption of this plume left a distinguishing mark: a spider-shaped feature on Europa's surface that was observed by Galileo imaging and incorporated into the researchers' model.

"Even though plumes generated by brine pocket migration would not provide direct insight into Europa's ocean, our findings suggest that Europa's ice shell itself is very dynamic," said co-lead author Joana Voigt, a graduate research assistant at the University of Arizona, in Tucson.

The relatively small size of the plume that would form at Manannán indicates that impact craters probably can't explain the source of other, larger plumes on Europa that have been hypothesized based on data from Galileo and NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, researchers said. But the process modeled for the Manannán eruption could happen on other icy bodies - even without an impact event. (NASA)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE