| News / Space News |

Powering Saturn's Active Ocean Moon

Heat from friction could power hydrothermal activity on Saturn's moon Enceladus for billions of years if the moon has a highly porous core, according to a new modeling study by European and U.S. researchers working on NASA's Cassini mission.

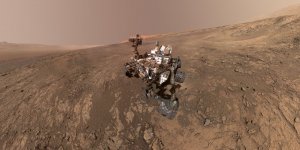

This graphic illustrates how water might be heated inside Enceladus. ![]()

Cassini found that Enceladus sprays towering, geyser-like jets of water vapor and icy particles, including simple organics, from warm fractures near its south pole.

Additional investigation revealed the moon has a global ocean beneath its icy crust, from which the jets are venting into space. Multiple lines of evidence from Cassini indicate that hydrothermal activity -- hot water interacting chemically with rock -- is taking place on the seafloor.

One of those lines was the detection of tiny rock grains inferred to be the product of hydrothermal chemistry taking place at temperatures of at least 194 degrees Fahrenheit (90 degrees Celsius). The amount of energy required to produce these temperatures is more than scientists think could be provided by decay of radioactive elements in the interior.

Gaël Choblet from the University of Nantes in France and co-authors found that a loose, rocky core with 20 to 30 percent empty space would do the trick. Their simulations show that as Enceladus orbits Saturn, rocks in the porous core flex and rub together, generating heat. The loose interior also allows water from the ocean to percolate deep down, where it heats up, then rises, interacting chemically with the rocks.

The models show this activity should be at a maximum at the moon's poles. Plumes of the warm, mineral-laden water gush from the seafloor and travel upward, thinning the moon's ice shell from beneath to only half a mile to 3 miles (1 to 5 kilometers) at the south pole. (The average global thickness of the ice is thought to be about 12 to 16 miles, or 20 to 25 kilometers.) And this same water is then expelled into space through fractures in the ice.

The study is the first to explain several key characteristics of Enceladus observed by Cassini: the global ocean, internal heating, thinner ice at the south pole, and hydrothermal activity. It doesn't explain why the north and south poles are so different though.

Unlike the tortured, geologically fresh landscape of the south, Enceladus' northern extremes are heavily cratered and ancient. The authors note that if the ice shell was slightly thinner in the south to begin with, it would lead to runaway heating there over time.

The researchers estimate that, over time (between 25 and 250 million years), the entire volume of Enceladus' ocean passes through the moon's core. This is estimated to be an amount of water equal to two percent of the volume of Earth's oceans. (NASA)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE