| Library / Biographies |

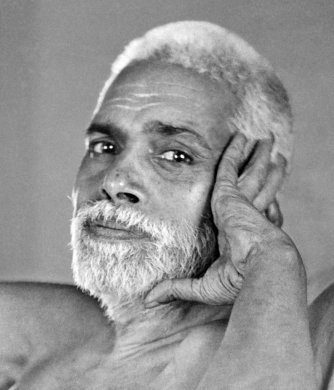

Ramana Maharshi Biography

Ramana Maharshi was born Venkataraman Iyer, in Tiruchuli, Tamil Nadu, India, on 30 December 1879, the day of Arudra Darśanam, a festival that commemorates the manifestation of Lord Śiva as Naṭarāja. His parents were Sundaram Iyer, a farmer, and his wife Alagammal; he was the second of their four children. Venkataraman's family was orthodox Hindu Brahmin belonged to the Smārta 1 denomination, and regularly worshiped in their home.

Venkataraman completed elementary school in Tiruchuzhi and in 1891 moved to Dindigul to attend high school, about 120km North from his hometown. In February 1892, his father died and the family was broken up. Without income to support the household, Venkataraman and his elder brother went to live with their paternal uncle in Madurai, while the two younger children remained with the mother. Venkataraman attended Scott’s Middle School and later joined American Mission High school. He preferred games and athletic activities to book learning, despite his amazing memory.

In November 1895 just before his 16th birthday, he met an elderly relative and was impressed to hear he was coming from Arunachala. He knew of Arunachala as being a very sacred place, but it never occurred to him one could go there. Soon after, he borrowed Periya Purāṇam 2 from his uncle. As he read it, he was overwhelmed with ecstatic wonder that such faith, love and divine fervor was possible. The tales of renunciation leading to divine union inspired him with awe and emulation.

Few months later, in July 1896, he experienced a state of violent fear of death and felt that he is going to die. He was drawn into a state of deep absorption, and was convinced that upon the body dissolution, the spirit remains untouched.

Years later he described this experience: “It was quite sudden. I was sitting in a room on the first floor of my uncle’s house. I seldom had any sickness and on that day; there was nothing wrong with my health, but a sudden, violent fear of death overtook me. There was nothing in my state of health to account for it; and I did not try to account for it or to find out whether there was any reason for the fear. I just felt, ‘I am going to die,’ and began thinking what to do about it. It did not occur to me to consult a doctor or my elders or friends. I felt that I had to solve the problem myself, then and there. The shock of the fear of death drove my mind inwards and I said to myself mentally, without actually framing the words: ‘Now death has come; what does it mean? What is it that is dying? This body dies.’ And I at once dramatized the occurrence of death. I lay with my limbs stretched out stiff as though rigor mortis had set in and imitated a corpse so as to give greater reality to the enquiry. I held my breath and kept my lips tightly closed so that no sound could escape, so that neither the word ‘I’ or any other word could be uttered, ‘Well then,’ I said to myself, ‘this body is dead. It will be carried stiff to the burning ground and there burnt and reduced to ashes. But with the death of this body am I dead? Is the body ‘I’? It is silent and inert but I feel the full force of my personality and even the voice of the ‘I’ within me, apart from it. So I am Spirit transcending the body. The body dies but the Spirit that transcends it cannot be touched by death. This means I am the deathless Spirit.’ All this was not dull thought; it flashed through me vividly as living truth which I perceived directly, almost without thought-process. ‘I’ was something very real, the only real thing about my present state, and all the conscious activity connected with my body was centered on that ‘I’. From that moment onwards the ‘I’ or Self focused attention on itself by a powerful fascination. Fear of death had vanished once and for all. Absorption in the Self continued unbroken from that time on. Other thoughts might come and go like the various notes of music, but the ‘I’ continued like the fundamental śruti note that underlies and blends with all the other notes. Whether the body was engaged in talking, reading, or anything else, I was still centered on ‘I’. Previous to that crisis I had no clear perception of my Self and was not consciously attracted to it. I felt no perceptible or direct interest in it, much less any inclination to dwell permanently in it.”

Six weeks later he left his uncle's home in Madurai for the holy mountain Arunachala, in Tiruvannamalai. On September 1st, 1896, three days after leaving home, Venkataraman arrived at the temple of Arunachaleśvara (Arunachala Īśvara). No one else was inside, and alone he entered the inner shrine and was overcome with faith: “I have come at your call, Lord. Accept me and do with me as you will.”

He spent the first few weeks in the thousand-pillared hall, then shifted to other spots in the temple, and eventually to the Patala-lingam vault so that he could remain undisturbed. There, he spent days absorbed in such deep samādhi that he was unaware of the bites of vermin and pests. Seshadri Swamigal, a local saint, discovered him in the underground vault and tried to protect him. After about six weeks in the Patala-lingam vault, where the sunlight never penetrated, he was carried out and cleaned up. For the next two months he stayed in the Subramanya Shrine, so unaware of his body and surroundings that food had to be placed in his mouth to keep him from starving.

In February 1897, six months after his arrival at Tiruvannamalai, Venkataraman moved to Gurumūrtam, a temple about a mile away. There, a sadhu named Palaniswami went to see him and was filled with peace and bliss. From that time on he served Venkataraman as his permanent attendant. Besides physical protection, Palaniswami would also beg for alms, cook and prepare meals for himself and Venkataraman, and care for him as needed. In May 1898 Venkataraman moved to a mango orchard next to Gurumūrtam.

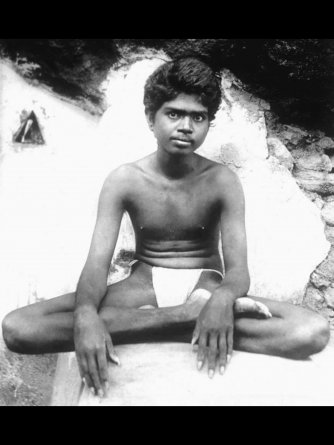

Venkataraman as a young man.

Gradually, despite Venkataraman's desire for privacy, he attracted attention from visitors who admired his silence and austerities, bringing offerings and singing praises. Eventually a bamboo fence was built to protect him.

While living at the Gurumurtam temple his family discovered his whereabouts. First, his uncle Nelliappa Iyer came and pleaded with him to return home, promising that the family would not disturb his ascetic life. Venkataraman sat motionless and eventually his uncle gave up.

In September 1898 Venkataraman moved to the Shiva-temple at Pavalakkunru, one of the eastern spurs of Arunachala. His mother later came accompanied by her eldest son Nagaswamy. With tears in her eyes Alagammal entreated her son to go back with her, but nothing moved him – not even his mother’s tears. He kept silent and sat still. Someone who had been observing the struggle of the mother for several days requested Ramana to write out some words for her. He wrote on a piece of paper:

“The Ordainer controls the fate of souls in accordance with their prārabdha karma 3. Whatever is destined not to happen will not happen, try how hard you may. Whatever is destined to happen will happen, do what you may to stop it. This is certain. The best course, therefore, is to remain silent.”

Soon after this, in February 1899, Venkataraman left the foothills to live on Arunachala itself. He stayed briefly in Satguru Cave and Guhu Namasivaya Cave before taking up residence at Virupaksha Cave for the next 17 years, using Mango Tree cave during the summers, except for a six-month period at Pachaiamman Koil during the plague epidemic.

First photo of the young Swami, taken in 1900 soon after his move onto the hill.

In 1902, a government official named Sivaprakasam Pillai, with writing slate in hand, visited the young Swami in the hope of obtaining answers to questions about "How to know one's true identity". The fourteen questions put to the young Swami and his answers were his first teachings on Self-enquiry, the method for which he became widely known, and were eventually published as “Nan Yar?”, or in English, “Who am I?”

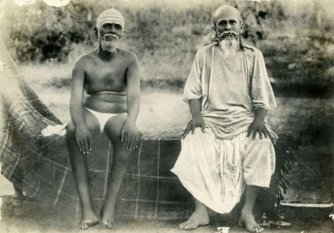

Ramana Maharsi and Śri Gaṇapati

Many visitors came to him and some became his devotees. Kavyakantha Śri Gaṇapati Śāstri, a Vedic scholar of repute in his age, with a deep knowledge of the Śrutis, Śāstra, Tantras, Yoga, and Āgama systems, but lacking the personal darśan 4 of Shiva, came to visit Venkataraman in 1907. After receiving upadesa from him on self-enquiry, he proclaimed him as Bhagavan Śri Ramana Maharshi. Ramana Maharshi was known by this name from then on. Gaṇapati Śāstri passed on these instructions to his own students, but later in life confessed that he had never been able to achieve permanent Self-abidance. Nevertheless, he was highly valued by Ramana Maharshi and played an important role in his life.

In 1911 the first westerner, Frank Humphreys, then a police officer stationed in India, discovered Ramana Maharshi and wrote articles about him which were first published in The International Psychic Gazette in 1913.

In the appendix to his book, Self Realization, B.V. Narasimha Swami5 wrote that in 1912, while in the company of disciples, Ramana Maharshi had an epileptic fit, in which his vision was suddenly impaired three times by a "white bright curtain" which covered a part of his vision. At the third instance his vision was shut out completely, while his "head was swimming", and he felt his heart stop beating and his breathing seizing, while his skin turned blue, as if he was dead. This lasted for about ten or fifteen minutes, thereafter "a shock passed suddenly through the body", and his blood circulation and his respiration returned. In response to "strange accounts" about this event, he later said that it was a fit, which he used to have occasionally, and did not bring on himself. According to Osborne, it "marked the final completion of Śri Bhagavan’s return to full outer normality".

In 1916 his mother and younger brother Nagasundaram joined Ramana Maharshi at Tiruvannamalai and followed him when he moved to the larger Skandashram Cave, where Bhagavan lived until the end of 1922. His mother took up the life of a saṃnyāsin 6 and Ramana Maharshi began to give her intense, personal instruction, while she took charge of the Ashram kitchen. Ramana Maharshi's younger brother, Nagasundaram, then became a saṃnyāsin also, assuming the name Niranjanananda, becoming known as Chinnaswami (the younger Swami).

During this period, Ramana Maharshi composed The Five Hymns to Arunachala, his magnum opus in devotional lyric poetry. The first hymn is Akshara Mana Malai. It was composed in Tamil in response to the request of a devotee for a song to be sung while wandering in the town for alms. The Marital Garland tells in glowing symbolism of the love and union between the human soul and God, expressing the attitude of the soul that still aspires.

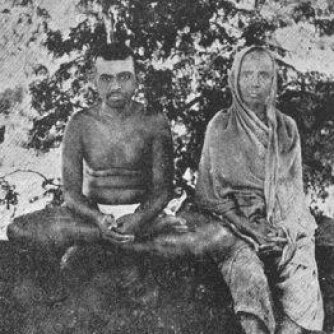

Starting in 1920, his mother's health deteriorated. She died on 19 May 1922 while Ramana Maharshi sat beside her.

Ramana Maharshi and his mother.

From 1922 until his death in 1950 Ramana Maharshi lived in Śri Ramanasramam, the ashram that developed around his mother's tomb. Ramana Maharshi often walked from Skandashram to his mother's tomb. In December 1922 he did not return to Skandashram, and settled at the base of the Hill, and Śri Ramanasramam started to develop.

Śri Ramana Maharshi led a modest and renunciate life. However, according to David Godman, who has written extensively about Ramana Maharshi, a popular image of him as a person who spent most of his time doing nothing except sitting silently in samadhi is highly inaccurate. From the period when an Ashram began to rise around him after his mother arrived, until his later years when his health failed, Ramana Maharshi was actually quite active in Ashram activities such as cooking and stitching leaf plates.

In 1931 the biography of Ramana Maharshi, “Self Realisation: The Life and Teachings of Ramana Maharshi,” written by B. V. Narasimha, was published. Ramana Maharshi then became relatively well known in and out of India after 1934 when Paul Brunton, having first visited Ramana Maharshi in January 1931, published the book “A Search in Secret India.” In this book he describes how he was compelled by the Paramacharya of Kanchi to meet Ramana Maharshi, his meeting with Ramana Maharshi, and the effect this meeting had on him.

Following the publishing of Brunton’s book, among the visitors were Paramahansa Yogananda, Somerset Maugham (whose 1944 novel The Razor's Edge models its spiritual guru after Ramana Maharshi), Mercedes de Acosta and Arthur Osborne, the last of whom was the first editor of Mountain Path in 1964, the magazine published by Ramanasramam.

In November 1948, a tiny cancerous lump was found on Ramana Maharshi's arm and was removed in February 1949 by the ashram's doctor. Soon, another growth appeared, and another operation was performed by an eminent surgeon in March 1949 with radium applied. The doctor told Ramana Maharshi that a complete amputation of the arm to the shoulder was required to save his life, but he refused. A third and fourth operation were performed in August and December 1949, but only weakened him.

Other systems of medicine were then tried; all proved fruitless and were stopped by the end of March when devotees gave up all hope. To devotees who begged him to cure himself for the sake of his followers, Ramana Maharshi is said to have replied, "Why are you so attached to this body? Let it go", and "Where can I go? I shall always be here." By April 1950, Ramana Maharshi was too weak to go to the hall and visiting hours were limited. Visitors would file past the small room where he spent his last days to get one final glimpse. He died on 14 April 1950 at 8:47PM.

Many devotees visited Ramana Maharshi for darśan, the sight of a holy person or God incarnate, which transmits merit. According to Osborne, Ramana Maharshi regarded giving darśan as "his task in life" and said that he had to be accessible to all who came. Even during his terminal illness at the end of his life, he demanded to be approachable for all who came to see him.

Objects being touched or used by him were highly valued by his devotees, "as they considered it to be prasad 7and that it passed on some of the power and blessing of the Guru to them". People also tried to touch his feet, which is also considered darśan. When one devotee asked if it would be possible to prostrate before Śri Ramana Maharshi and touch his feet, he replied: “The real feet of Bhagavan exist only in the heart of the devotee. To hold onto these feet incessantly is true happiness. You will be disappointed if you hold onto my physical feet because one day this physical body will disappear. The greatest worship is worshipping the Guru's feet that are within oneself.”

Ramana Maharshi provided spiritual instruction by sitting silently together with devotees and visitors, but also by answering the questions and concerns raised by those who sought him out. Many of these question-and-answer sessions have been transcribed and published by devotees, some of which have been edited by Ramana Maharshi himself. A few texts have been published which were written by Ramana Maharshi himself or written down on his behalf and edited by him.

Ramana Maharshi did not publicize himself as a guru, never claimed to have disciples, and never appointed any successors. He did not publicly acknowledge any living person as liberated other than his mother at death. Ramana Maharshi never promoted any lineage.

Books on Ramana Maharshi

• Be As You Are by David Godman

• Day to Day with Bhagavan by Arthur Osbourne

• The Collected Works of Ramana Maharshi by Arthur Osbourne

• A Search in a Secret India by Paul Brunton

Footnotes

1. Smārta (phil. traditional, legal; that follows the tradition [smṛti]) is a movement in Hinduism that developed during its classical period around the beginning of the Common Era. It reflects a Hindu synthesis of four philosophical strands: Mīmāṃsā, Advaita, Yoga, and theism. The Smārta tradition rejects theistic sectarianism, and it is notable for the domestic worship of five shrines with five deities, all treated as equal – Śiva, Viṣṇu, Sūrya, Gaṇeśa, and Śakti. There has been considerable overlap in the ideas and practices of the Smārta tradition with other significant historic movements within Hinduism, namely Śaivism, Brahmanism, Viṣṇaivism, and Śaktism. The Smārta tradition is aligned with Advaita Vedānta, and regards Ādi Śankara as its founder or reformer.

2. The Periya Puranam (The Great Epic) sometimes called Tiruttontarpuranam (the Purana of the Holy Devotees), is a Tamil poetic account depicting the lives of the sixty-three Nayanars, the canonical poets of Tamil Shaivism. It was compiled during the 12th century by Sekkizhar. The Periya Purāṇam is part of the corpus of Shaiva canonical works.

3. According to Swami Sivananda: "Prarabdha is that portion of the past karma which is responsible for the present body. That portion of the sanchita karma (one of the three kinds of karma) which influences human life in the present incarnation is called prarabdha. It is ripe for reaping. It cannot be avoided or changed. It is only exhausted by being experienced. You pay your past debts. Prarabdha karma is that which has begun and is actually bearing fruit. It is selected out of the mass of the sanchita karma."

4. Darśana (Sanskrit: lit. view, sight) is the auspicious sight of a deity or a holy person. The term darśana also refers to the six systems of thought that comprise classical Hindu philosophy. The term therein implies how each of these six systems distinctively look at things and the scriptures in Indian philosophies. The six orthodox Hindu darśana are Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedānta. Buddhism and Jainism are examples of non-Hindu darśanas.

5. Narasimha Swami was a lawyer who in 1925 left home and went in search of an authentic spiritual master. He was advised to visit and seek the blessings of Ramana Maharishi in Tiruvannamalai. He accordingly went to Tiruvannamalai and stayed there in one of the caves observing silence for 3 years and concentrated on the study of Vedanta. During his stay in Tiruvannamalai he wrote the biography of Ramana Maharishi under the title “Self Realisation” in English.

6. Saṃnyāsa is the life stage of renunciation within the Hindu philosophy of four age-based life stages known as āśrama, with the first three being Brahmacharya (bachelor student), Grihastha (householder) and Vānaprastha (forest dweller, retired). Sannyasa is traditionally conceptualized for men or women in late years of their life, but young brahmacharis have had the choice to skip the householder and retirement stages, renounce worldly and materialistic pursuits and dedicate their lives to spiritual pursuits.

7. 'Prasāda' literally means a gracious gift. It denotes anything, typically an edible food, that is first offered to a deity, saint, Perfect Master or an avatār, and then distributed in His or Her name to their followers or others as a good sign.