| News / Science News |

Rare earth element’s secrets exposed

Scientists have uncovered the properties of a rare earth element that was first discovered 80 years ago at the very same laboratory, opening a new pathway for the exploration of elements critical in modern technology, from medicine to space travel.

Conceptual art shows the rare earth element promethium in a vial surrounded by an organic ligand. ORNL scientists have discovered hidden features of promethium, opening a pathway for research into other lanthanide elements. Credit: Jacquelyn DeMink, art; Thomas Dyke, photography/ORNL, U.S. Dept. of Energy

Promethium was discovered in 1945 at Clinton Laboratories, now the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and continues to be produced at ORNL in minute quantities.

Some of its properties have remained elusive despite the rare earth element’s use in medical studies and long-lived nuclear batteries. It is named after the mythological Titan who delivered fire to humans and whose name symbolizes human striving.

“The whole idea was to explore this very rare element to gain new knowledge,” said Alex Ivanov, an ORNL scientist who co-led the research. “Once we realized it was discovered at this national lab and the place where we work, we felt an obligation to conduct this research to uphold the ORNL legacy.”

The ORNL-led team of scientists prepared a chemical complex of promethium, which enabled its characterization in solution for the first time. Thus, they exposed the secrets of this extremely rare lanthanide, whose atomic number is 61, in a series of meticulous experiments.

“Because it has no stable isotopes, promethium was the last lanthanide to be discovered and has been the most difficult to study,” said ORNL’s Ilja Popovs, who co-led the research. Most rare earth elements are lanthanides, elements from 57 — lanthanum — to 71 — lutetium — on the periodic table. They have similar chemical properties but differ in size.

The other 14 lanthanides are well understood. They are metals with useful properties that make them indispensable in many modern technologies. They are workhorses of applications such as lasers, permanent magnets in wind turbines and electric vehicles, X-ray screens and even cancer-fighting medicines.

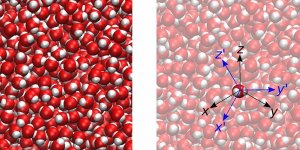

The ORNL scientists bound, or chelated, radioactive promethium with special organic molecules called diglycolamide ligands. Then, using X-ray spectroscopy, they determined the properties of the complex, including the length of the promethium chemical bond with neighboring atoms — a first for science and a longstanding missing piece to the periodic table of elements.

Promethium is very rare; only about a pound occurs naturally in the Earth’s crust at any given time. Unlike other rare earth elements, only minute quantities of synthetic promethium are available because it has no stable isotopes.

For this study, the ORNL team produced the isotope promethium-147, with a half-life of 2.62 years, in sufficient quantities and at a high enough purity to study its chemical properties. ORNL is the United States’ only producer of promethium-147.

Notably, the team provided the first demonstration of a feature of lanthanide contraction in solution for the whole lanthanide series, including promethium, atomic number 61. Lanthanide contraction is a phenomenon in which elements with atomic numbers between 57 and 71 are smaller than expected. As the atomic numbers of these lanthanides increase, the radii of their ions decrease.

This contraction creates distinctive chemical and electronic properties because the same charge is limited to a shrinking space. The ORNL scientists got a clear promethium signal, which enabled them to better define the shape of the trend — across the series.

“It’s really astonishing from a scientific viewpoint. I was struck once we had all the data,” said Ivanov. “The contraction of this chemical bond accelerates along this atomic series, but after promethium, it considerably slows down. This is an important landmark in understanding the chemical bonding properties of these elements and their structural changes along the periodic table.”

Many of these elements, such as those in the lanthanide and actinide series, have applications ranging from cancer diagnostics and treatment to renewable energy technologies and long-lived nuclear batteries for deep space exploration.

The achievement will, among other things, ease the difficult job of separating these valuable elements, according to Jansone-Popova. The team has long worked on separations for the whole series of lanthanides, “but promethium was the last puzzle piece. It was quite challenging,” she said. “You cannot utilize all these lanthanides as a mixture in modern advanced technologies, because first you need to separate them. This is where the contraction becomes very important; it basically allows us to separate them, which is still quite a difficult task.”

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE