| Health / Health News |

Researchers connect brain blood vessel lesions to intestinal bacteria

A study in mice and humans suggests that bacteria in the gut can influence the structure of the brain’s blood vessels, and may be responsible for producing malformations that can lead to stroke or epilepsy.

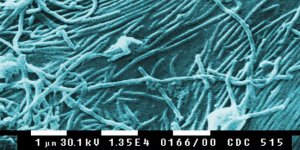

Histology of a cavernous hemangioma. ![]()

The research adds to an emerging picture that connects intestinal microbes and disorders of the nervous system.

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) are clusters of dilated, thin-walled blood vessels that can lead to seizures or stroke when blood leaks into the surrounding brain tissue.

A team of scientists at the University of Pennsylvania investigated the mechanisms that cause CCM lesions to form in genetically engineered mice and discovered an unexpected link to bacteria in the gut. When bacteria were eliminated the number of lesions was greatly diminished.

The researchers were studying a well-established mouse model that forms a significant number of CCMs following the injection of a drug to induce gene deletion. However, when the animals were relocated to a new facility, the frequency of lesion formation decreased to almost zero.

Few mice that continued to form lesions had developed bacterial abscesses in their abdomens — infections that most likely arose due to the abdominal drug injections.

The abscesses contained Gram-negative bacteria, and when similar bacterial infections were deliberately induced in the CCM model animals, about half of them developed significant CCMs.

The mice that formed CCMs also had abscesses in their spleens, which meant that the bacteria had entered the bloodstream from the initial abscess site. This suggested a connection between the spread of a specific type of bacteria through the bloodstream and the formation of these blood vascular lesions in the brain.

The question remained as to how bacteria in the blood could influence blood vessel behavior in the brain.

Gram-negative bacteria produce molecules called lipopolysaccharides (LPS) that are potent activators of innate immune signaling. When the mice received injections of LPS alone, they formed numerous large CCMs, similar to those produced by bacterial infection.

Conversely, when the LPS receptor, TLR4, was genetically removed from these mice they no longer formed CCM lesions. The researchers also found that, in humans, genetic mutations causing an increase in TLR4 expression were associated with a greater risk of forming CCMs.

Newborn CCM mice were raised in either normal housing or under germ-free conditions.

These mice were given a course of antibiotics to “reset” their microbiome. In both the germ-free conditions and following the course of antibiotics, the number of lesions was significantly reduced, indicating that both the quantity and quality of the gut microbiome could affect CCM formation. A drug that specifically blocks TLR4 also produced a significant decrease in lesion formation. (NIH)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE