| News / Science News |

Researchers identify key brain circuits for reward-seeking and avoidance behavior

Researchers have identified connections between neurons in brain systems associated with reward, stress, and emotion. Conducted in mice, the new study may help untangle multiple psychiatric conditions, including alcohol use disorder, anxiety disorders, insomnia, and depression in humans.

Human brain in the coronal orientation. Amygdalae are shown in dark red. ![]()

Understanding these intricate brain systems will be critical for developing diagnostic and therapeutic tools for a broad array of conditions.

Responding appropriately to aversive or rewarding stimuli is essential for survival. This requires fine-tuned regulation of brain systems that enable rapid responses to changes in the environment, such as those involved in sleep, wakefulness, stress, and reward-seeking. These same brain systems are often dysregulated in addiction and other psychiatric conditions.

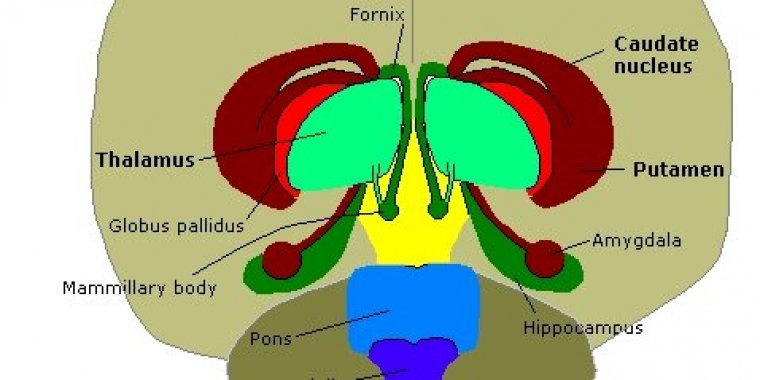

In the new study, researchers looked at the extended amygdala, a brain region involved in fear, arousal, and emotional processing and which plays a significant role in drug and alcohol addiction. They focused on a part of this structure known as the bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BNST), which connects the extended amygdala to the hypothalamus, a brain region that regulates sleep, appetite, and body temperature.

The hypothalamus is also thought to promote both negative and positive emotional states. A better understanding of how the BNST and hypothalamus work to coordinate emotion-related behavior could shed light on the emotional processes dysregulated in addiction.

These circuits, also implicated in binge drinking, are likely to be elements in understanding the detailed mechanisms driving stress-related alcohol- or drug-seeking and consummatory behaviors.

To map the brain circuitry between the BNST and the hypothalamus, Dr. William Giardino and colleagues at Stanford University exposed mice to rewarding and aversive stimuli, and then visualized and manipulated the activity of neurons using fiber optic techniques.

The scientists identified two distinct subpopulations of neurons in the BNST that connect to separate populations of neurons in the lateral hypothalamus. These parallel circuits drove opposing emotional states: avoidance (aversion) and approach (preference).

Different neurotransmitters were linked to aversion and preference within these neurocircuits – corticotropin releasing factor was involved in aversion, while cholecystokinin played a role in preference.

The authors note that future studies of the BNST to LH pathways will inform the development of improved therapeutic approaches for psychiatric disorders. (National Institutes of Health)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE