| Health / Health News |

Salmonella use intestinal epithelial cells to colonize the gut

The immune system’s attempt to eliminate Salmonella bacteria from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract instead facilitates colonization of the intestinal tract and fecal shedding, according to National Institutes of Health scientists.

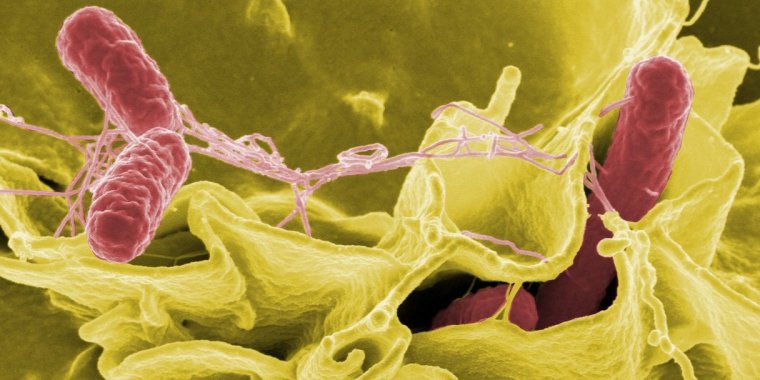

Salmonella bacteria, a common cause of food poisoning, invade an immune cell. Photo: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Salmonella Typhimurium bacteria (hereafter Salmonella) live in the gut and often cause gastroenteritis in people. Contaminated food is the source for most of these illnesses.

Most people who get ill from Salmonella have diarrhea, fever and stomach cramps but recover without specific treatment. Antibiotics typically are used only to treat people who have severe illness or who are at risk for it.

Salmonella bacteria also can infect a wide variety of animals, including cattle, pigs and chickens. Although clinical disease usually resolves within a few days, the bacteria can persist in the GI tract for much longer. Fecal shedding of the bacteria facilitates transmission to new hosts, especially by so-called “super shedders” that release high numbers of bacteria in their feces.

NIAID scientists are studying how Salmonella bacteria establish and maintain a foothold in the GI tract of mammals. One of the first lines of defense in the GI tract is the physical barrier provided by a single layer of intestinal epithelial cells. These specialized cells absorb nutrients and are a critical barrier that prevents pathogens from spreading to deeper tissues.

When bacteria invade these cells, the cells are ejected into the gut lumen—the hollow portion of the intestines. However, in previous studies, NIAID scientists had observed that some Salmonella replicate rapidly in the cytosol—the fluid portion—of intestinal epithelial cells. That prompted them to ask: does ejecting the infected cell amplify rather than eliminate the bacteria?

To address this question, the scientists genetically engineered Salmonella bacteria that self-destruct when exposed to the cytosol of epithelial cells but grow normally in other environments, including the lumen of the intestine.

Then they infected laboratory mice with the self-destructing Salmonella bacteria and found that replication in the cytosol of mouse intestinal epithelial cells is important for colonization of the GI tract and fuels fecal shedding.

The scientists hypothesize that, by hijacking the epithelial cell response, Salmonella amplify their ability to invade neighboring cells and seed the intestine for fecal shedding.

The researchers say this is an example of how the pressure exerted by the host immune response can drive the evolution of a pathogen, and vice versa. The new insights offer new avenues for developing novel interventions to reduce the burden of this important pathogen. (National Institutes of Health)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE