| News / Science News |

Scientists discover new antibiotic in tropical forest

Scientists have discovered an antibiotic produced by a soil bacterium in a Mexican tropical forest that may help lead to a "plant probiotic."

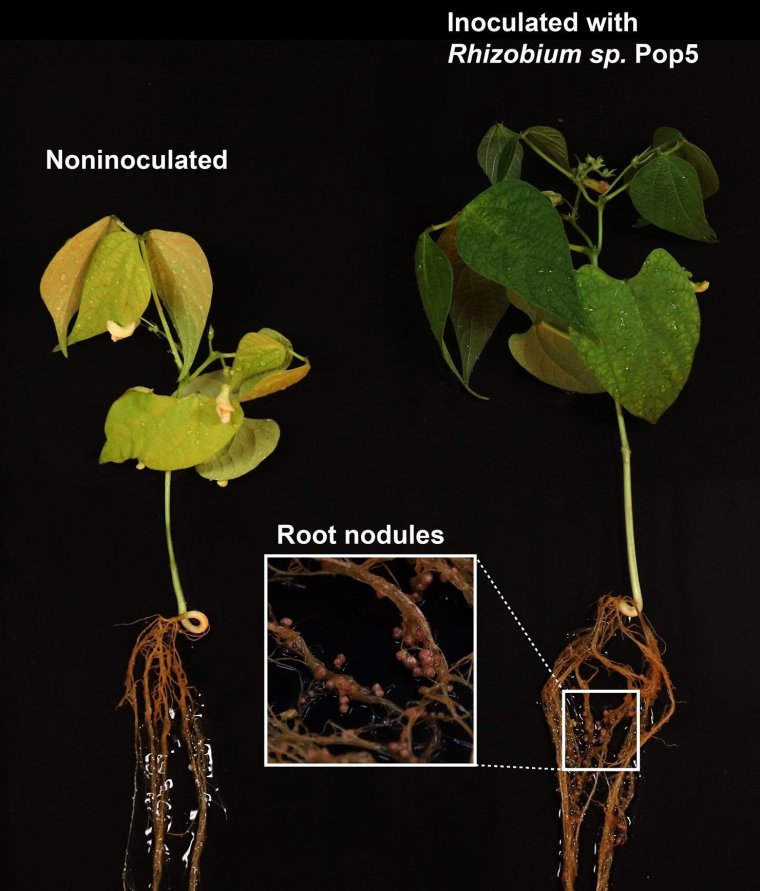

The bacterium that produces the antibiotic phazolicin results in a more robust plant. Photo: Dmitrii Y. Travin

Probiotics, which provide health benefits to humans, can also keep plants robust. The new antibiotic, known as phazolicin, prevents harmful bacteria from entering root systems of bean plants.

"We hope to show the bacterium can be used as a 'plant probiotic' because phazolicin will prevent other, potentially harmful bacteria from growing in the root systems of agriculturally important plants," said senior author Konstantin Severinov of Rutgers University. "Antibiotic resistance is a huge problem in both medicine and agriculture, and continuing searches for new antibiotics are very important as they may provide leads for future anti-bacterial agents."

The bacterium producing phazolicin is an unidentified species of Rhizobium. It was found in a tropical forest in Los Tuxtlas, Mexico, in soil and roots of wild beans called Phaseolus vulgaris, hence the antibiotic's name: phazolicin.

Like other Rhizobia, the phazolicin-producing microbe forms nodules on bean plant roots and provides the plants with nitrogen. Unlike other Rhizobia, it also defends plants from harmful bacteria sensitive to phazolicin. The phenomenon could be exploited in beans, peas, chickpeas, lentils, peanuts, soybeans and other legumes.

Using computer and bioinformatic analyses, the scientists predicted the existence of phazolicin, then confirmed its existence in the lab. They revealed the atomic structure of the antibiotic and showed that it's bound to and targets the ribosome, a protein production factory in bacterial cells.

The scientists found they can modify and control sensitivity, or susceptibility, to the antibiotic by introducing mutations in ribosomes. (National Science Foundation)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE