| Health / Health News |

Scientists successfully deliver “Trojan horse” catalysts into cancerous tumour cells to destroy them from within

Using “Trojan horses” to combat cancer from within the tumour cells themselves without damaging healthy tissues is the aim of this new tool created by researchers from the University of Granada (UGR), the Institute of Nanoscience of Aragon (INA), the University of Zaragoza, and the Cancer Research UK Edinburgh Centre at the University of Edinburgh.

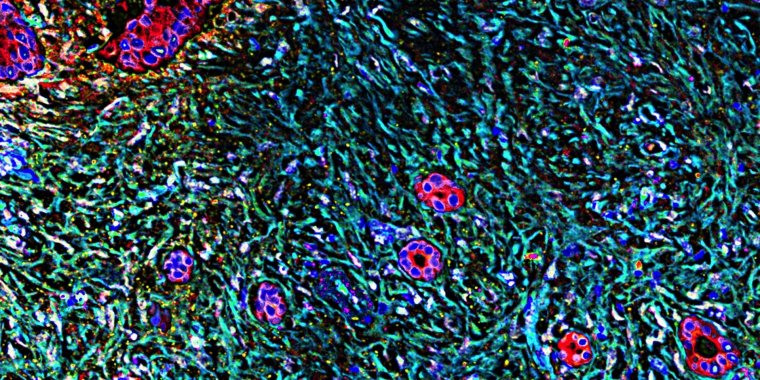

Pancreatic cancer. Photo: Neelima Shah and Edna Cukierman, Fox Chase Cancer Center/National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health

The researchers have used exosomes as “Trojan horses” to deliver palladium (Pd) catalysts into cancer cells. “We introduce the catalyst into tiny vesicles or exosomes the size of about 100 nanometres, which are capable of traveling right inside the tumorous cell. Once there, they catalyse a reaction that transforms a passive molecule into a potent anticancer agent,” explains Professor Jesús Santamaría of the University of Zaragoza.

Killing a cancer cell is straightforward: there are many toxic molecules that can perform the task. The challenge is to target the toxic molecule at the cancer cell only, and not at healthy cells.

This lack of selectivity in directing anticancer drugs is the cause of the often devastating side effects that cancer patients experience during chemotherapy treatment. Rather than injecting such drugs into the bloodstream, it would be much better if they could be manufactured directly inside the cancer cells. And that is precisely what this international team of scientists has achieved.

“We use catalysts in many aspects of everyday life because they generate chemical reactions that would not otherwise be possible. For example, the gases emitted by our cars pass through a catalyst to make them less harmful to the environment and our health,” comments Belén Rubio Ruiz of the UGR. It is therefore surprising that catalysis, which is known to be so useful in so many fields, is practically unheard-of in oncology. “This is due to the fact that there are tremendous obstacles: identifying suitable catalysts and reactions and, above all, delivering the catalysts directly into the target cells, and not others.”

However, exosomes may prove to be the key. Exosomes are secreted by most cells and are surrounded by a membrane containing elements that are characteristic of the cell from which they originate. This renders them selective (thanks to the phenomenon of tropism toward the cells of origin), and makes it possible for them to carry a therapeutic load preferentially to the original cell, even in the presence of other cells.

The authors of the study have found a way to induce the synthesis of catalysts (Pd nanosheets with a thickness of just over one nanometre) inside tumour cell exosomes without disturbing the properties of their membranes—thus converting the exosomes into “Trojan horses” capable of delivering the catalyst to the progenitor cancer cells. Once there, they catalyse the in situ synthesis of an anticancer compound (panobinostat, an anticancer drug approved in 2015).

Having demonstrated the effectiveness of this process in their study, the researchers observe: “We collected exosomes of the same type of cancerous cell that was to be treated, we loaded them with the palladium catalyst and returned them to the culture medium. There, thanks to their selective tropism, the exosomes deliver the catalyst to the original cell.

Once inside, the catalyst converts the inactive panobinostat into its active and toxic form, thus killing off the tumour cell just where we want: right inside the tumour cell.”

The key to the process is selectivity of the transport mechanism mediated by exosomes. Thanks to this selectivity, panobinostat is only generated within the cells that the catalyst has reached, and hence it preferentially causes the death of the original tumour cells, while the mortality rate among other cells is much lower. (Universities of Granada)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE