| News / Science News |

Selective amnesia: how rats and humans are able to actively forget distracting memories

Our ability to selectively forget distracting memories is shared with other mammals, suggests new research from the University of Cambridge.

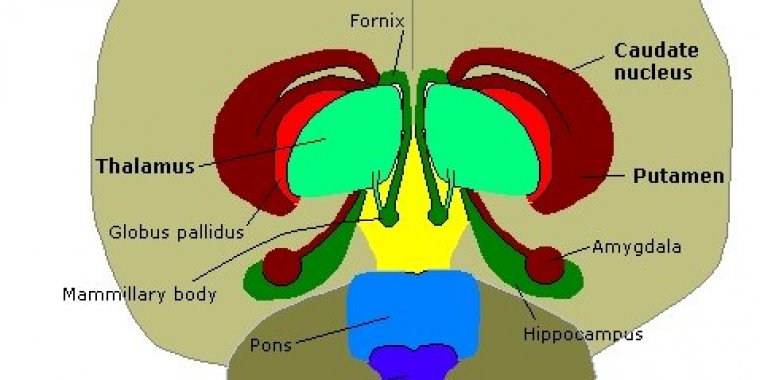

Human brain in the coronal orientation. ![]()

The discovery that rats and humans share a common active forgetting ability – and in similar brain regions – suggests that the capacity to forget plays a vital role in adapting mammalian species to their environments, and that its evolution may date back at least to the time of our common ancestor.

The human brain is estimated to include some 86 billion neurons (or nerve cells) and as many as 150 trillion synaptic connections, making it a powerful machine for processing and storing memories.

We need to retrieve these memories to help us carry out our daily tasks, whether remembering where we left the car in the supermarket car park or recalling the name of someone we meet in the street. But the sheer scale of the experiences people could store in memory over our lives creates the risk of being overwhelmed with information.

When we come out of the supermarket and think about where we left the car, for example, we only need to recall where we parked the car today, rather than being distracted by recalling every single time we came to do our shopping.

Humans possess the ability to actively forget distracting memories, and that retrieval plays a crucial role in this process. Intentional recall of a past memory is more than simply reawakening it; it actually leads us to forget other competing experiences that interfere with retrieval of the memory we seek.

While this process improves the efficiency of memory, it can sometimes lead to problems. If the police interview a witness to a crime, for example, their repeated questioning about selected details might lead the witness to forget information that could later prove important.

Although the ability to actively forget has been seen in humans, it is unclear whether it occurs in other species.

In a study published today has shown that the ability to actively forget is not a peculiarly human characteristic: rats, too, share our capacity for selective forgetting and use a very similar brain mechanism, suggesting this is an ability shared among mammals.

Rats appear to have the same active forgetting ability as humans do – they forget memories selectively when those memories cause distraction. And, crucially, they use a similar prefrontal control mechanism as we do.

This discovery suggests that this ability to actively forget less useful memories may have evolved far back on the ‘Tree of Life’, perhaps as far back as our common ancestor with rodents some 100 million years ago.

Now, that we know that the brain mechanisms for this process are similar in rats and humans, it should be possible to study this adaptive forgetting phenomenon at a cellular – or even molecular – level.

A better understanding of the biological foundations of these mechanisms may help researchers develop improved treatments to help people forget traumatic events. (University of Cambridge)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE