| News / Science News |

Six-decade-old space mystery solved with shoebox-sized satellite called a CubeSat

A 60-year-old mystery about the source of energetic, potentially damaging particles in Earth's radiation belts has been solved using data from a shoebox-sized satellite built and operated by students. The satellite is called a CubeSat.

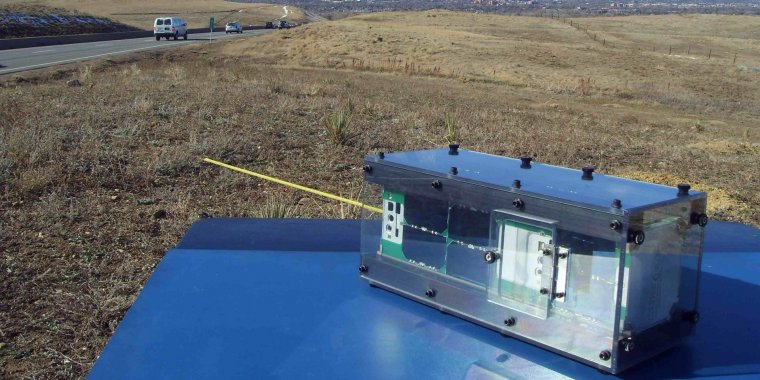

Researchers test the CubeSat, which is communicating with a ground station about four miles away. Image Credit: University of Colorado Boulder

CubeSats, named for the roughly 4-inch-cubed dimensions of their basic building elements, are stacked with smartphone-like electronics and tiny scientific instruments.

Built mainly by students and hitching rides into orbit on NASA and U.S. Department of Defense launch vehicles, the small, low-cost satellites have been making history.

Now, results from a new study using CubeSats indicate that energetic electrons in Earth's inner radiation belt -- primarily near its inner edge -- are created by cosmic rays born from supernova explosions.

Earth's dual radiation belts, known as the Van Allen belts, are layers of energetic particles held in place by the planet's magnetic field.

Soon after the discovery of the Van Allen radiation belts in 1958, American and Russian scientists concluded that the process of "cosmic ray albedo neutron decay" (CRAND) was likely the source of the high-energy particles trapped in Earth's magnetic field. But over the following decades, no one successfully detected the corresponding electrons that should be produced during the neutron decay.

During CRAND, cosmic rays entering Earth's atmosphere collide with neutral atoms, creating a splash that produces charged particles, including electrons, that become trapped by Earth's magnetic field.

The findings have implications for understanding and better forecasting the arrival of energetic electrons from space, which can damage satellites and threaten the health of space-walking astronauts.

The CubeSat mission, called the Colorado Student Space Weather Experiment (CSSWE), housed a small telescope to measure the flux of solar energetic protons and Earth's radiation belt electrons.

Launched in 2012 aboard an Atlas V rocket, CSSWE involved more than 65 students and was operated for more than two years from a ground station on the roof of a building on the University of Colorado Boulder campus. (National Science Foundation)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE