| News / World News |

The Southern Hemisphere is stormier than the Northern, and we finally know why

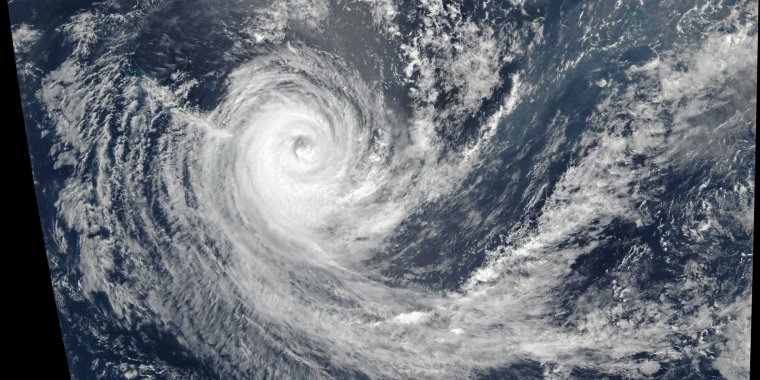

For centuries, sailors have known where the most fearsome storms are located: the Southern Hemisphere. "The waves ran mountain-high and threatened to overwhelm [the ship] at every roll," wrote one passenger on an 1849 voyage rounding the tip of South America.

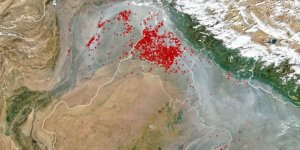

Cyclone in the South Pacific. Photo: NASA

Decades later, scientists poring over satellite data could finally put numbers behind that experience. The Southern Hemisphere is indeed stormier than the Northern, by about 24%. But no one knew why.

A study led by University of Chicago climate scientist Tiffany Shaw lays out the first concrete explanation for this phenomenon.

Shaw and colleagues found two major culprits: ocean circulation and large mountain ranges in the Northern Hemisphere.

The study also found that this storminess asymmetry has increased since the beginning of the satellite era in the 1980s. The increase was consistent with climate change forecasts.

Once, scientists didn't know much about weather in the Southern Hemisphere. Most of the ways we observe weather are land-based, and the Southern Hemisphere has much more ocean than the Northern Hemisphere.

But with the advent of satellite-based global observing in the 1980s, researchers could quantify how extreme the difference was. The Southern Hemisphere has a stronger jet stream and more intense weather events.

Scientists used a numerical model of Earth's climate built on the laws of physics; the model reproduced the observations. Then the researchers removed variables one at a time and quantified each one's impact on storminess.

The first variable tested was topography. Large mountain ranges disrupt air flow in a way that reduces storms, and there are more mountain ranges in the Northern Hemisphere.

When the scientists flattened every mountain on Earth, about half the difference in storminess between the two hemispheres disappeared.

The other half had to do with ocean circulation. Water moves around the globe like a very slow but powerful conveyor belt: it sinks in the Arctic, travels along the bottom of the ocean, rises near Antarctica and then flows up to the surface, carrying energy with it.

That creates an energy difference between the two hemispheres.

When the scientists tried eliminating the conveyor belt, they saw the other half of the difference in storminess disappear.

Next, the researchers moved on to examine how storminess has changed since they've been able to track it. Looking over past decades, storminess asymmetry has increased since the 1980s.

The Southern Hemisphere is getting even stormier, whereas the change on average in the Northern Hemisphere has been negligible.

The Southern Hemisphere storminess changes are connected to changes in the ocean. The researchers found that a similar ocean influence is occurring in the Northern Hemisphere, but its effect is canceled out by the absorption of sunlight due to the loss of sea ice and snow. (U.S. National Science Foundation)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE