| News / Science News |

Star Dance Around Supermassive Black Hole, Proves Einstein Right

Observations made with ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) have revealed for the first time that a star orbiting the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way moves just as predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Its orbit is shaped like a rosette and not like an ellipse as predicted by Newton's theory of gravity.

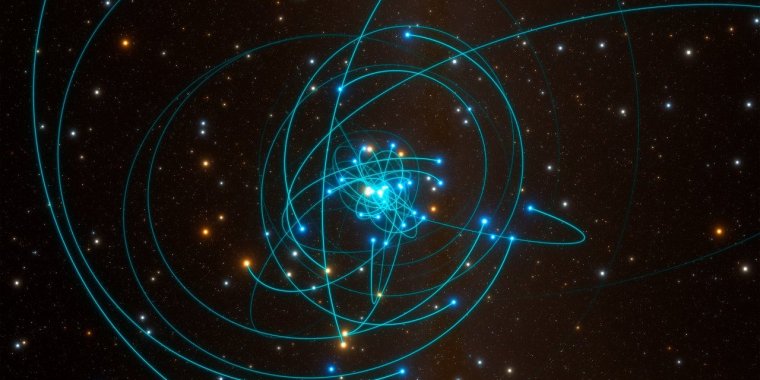

Orbits of stars around black hole at the heart of the Milky Way. Photo: ESO

This long-sought-after result was made possible by increasingly precise measurements over nearly 30 years, which have enabled scientists to unlock the mysteries of the behemoth lurking at the heart of our galaxy.

“Einstein’s General Relativity predicts that bound orbits of one object around another are not closed, as in Newtonian Gravity, but precess forwards in the plane of motion. This famous effect — first seen in the orbit of the planet Mercury around the Sun — was the first evidence in favour of General Relativity.

One hundred years later we have now detected the same effect in the motion of a star orbiting the compact radio source Sagittarius A* at the centre of the Milky Way.

This observational breakthrough strengthens the evidence that Sagittarius A* must be a supermassive black hole of 4 million times the mass of the Sun,” says Reinhard Genzel, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) in Garching, Germany.

Located 26 000 light-years from the Sun, Sagittarius A* and the dense cluster of stars around it provide a unique laboratory for testing physics in an otherwise unexplored and extreme regime of gravity.

One of these stars, S2, sweeps in towards the supermassive black hole to a closest distance less than 20 billion kilometres (one hundred and twenty times the distance between the Sun and Earth), making it one of the closest stars ever found in orbit around the massive giant.

At its closest approach to the black hole, S2 is hurtling through space at almost three percent of the speed of light, completing an orbit once every 16 years. “After following the star in its orbit for over two and a half decades, our exquisite measurements robustly detect S2’s Schwarzschild precession in its path around Sagittarius A*,” says Stefan Gillessen of the MPE.

Most stars and planets have a non-circular orbit and therefore move closer to and further away from the object they are rotating around. S2’s orbit precesses, meaning that the location of its closest point to the supermassive black hole changes with each turn, such that the next orbit is rotated with regard to the previous one, creating a rosette shape.

General Relativity provides a precise prediction of how much its orbit changes and the latest measurements from this research exactly match the theory. This effect, known as Schwarzschild precession, had never before been measured for a star around a supermassive black hole.

“Because the S2 measurements follow General Relativity so well, we can set stringent limits on how much invisible material, such as distributed dark matter or possible smaller black holes, is present around Sagittarius A*. This is of great interest for understanding the formation and evolution of supermassive black holes,” say Guy Perrin and Karine Perraut, the French lead scientists of the project.

With ESO’s upcoming Extremely Large Telescope, the team believes that they would be able to see much fainter stars orbiting even closer to the supermassive black hole. “If we are lucky, we might capture stars close enough that they actually feel the rotation, the spin, of the black hole,” says Andreas Eckart from Cologne University.

This would mean astronomers would be able to measure the two quantities, spin and mass, that characterise Sagittarius A* and define space and time around it. “That would be again a completely different level of testing relativity". (ESO)

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE