| News / Science News |

Study finds out why some words may be more memorable than others

Thousands of words, big and small, are crammed inside our memory banks just waiting to be swiftly withdrawn and strung into sentences. In a recent study of epilepsy patients and healthy volunteers, National Institutes of Health researchers found that our brains may withdraw some common words, like “pig,” “tank,” and “door,” much more often than others, including “cat,” “street,” and “stair.”

NIH study suggests our brains may use search engine strategies to remember words and memories of our past experiences. Photo: Zaghloul lab, NIH/NINDS.

By combining memory tests, brain wave recordings, and surveys of billions of words published in books, news articles and internet encyclopedia pages, the researchers not only showed how our brains may recall words but also memories of our past experiences.

“We found that some words are much more memorable than others. Our results support the idea that our memories are wired into neural networks and that our brains search for these memories, just the way search engines track down information on the internet,” said Weizhen (Zane) Xie, Ph.D., a cognitive psychologist and post-doctoral fellow at the NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), who led the study.

Dr. Xie and his colleagues first spotted these words when they re-analyzed the results of memory tests taken by 30 epilepsy patients who were part of a clinical trial led by Kareem Zaghloul, M.D., Ph.D., a neurosurgeon and senior investigator at NINDS.

The memory tests were originally designed to assess episodic memories, or the associations – the who, what, where and how details - we make with our past experiences. Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia often destroys the brain’s capacity to make these memories.

Patients were shown pairs of words, such as “hand” and “apple,” from a list of 300 common nouns. A few seconds later they were shown one of the words, for instance “hand,” and asked to remember its pair, “apple.”

Dr. Zaghloul’s team had used these tests to study how neural circuits in the brain store and replay memories.

When Dr. Xie and his colleagues re-examined the test results, they found that patients successfully recalled some words more often than others, regardless of the way the words were paired.

In fact, of the 300 words used, the top five were on average about seven times more likely to be successfully recalled than the bottom five.

At first, Dr. Zaghloul and the team were surprised by the results and even a bit skeptical.

For many years scientists have thought that successful recall of a paired word meant that a person’s brain made a strong connection between the two words during learning and that a similar process may explain why some experiences are more memorable than others.

Also, it was hard to explain why words like “tank,” “doll,” and “pond” were remembered more often than frequently used words like “street,” “couch,” and “cloud.”

But any doubts were quickly diminished when the team saw very similar results after 2,623 healthy volunteers took an online version of the word pair test.

“Our memories play a fundamental role in who we are and how our brains work. However, one of the biggest challenges of studying memory is that people often remember the same things in different ways, making it difficult for researchers to compare people’s performances on memory tests,” said Dr. Xie.

“For over a century, researchers have called for a unified accounting of this variability. If we can predict what people should remember in advance and understand how our brains do this, then we might be able to develop better ways to evaluate someone’s overall brain health.”

In this paper, Dr. Xie proposed that the principles from an established theory, known as the Search for Associative Memory (SAM) model, may help explain their initial findings with the epilepsy patients and the healthy controls.

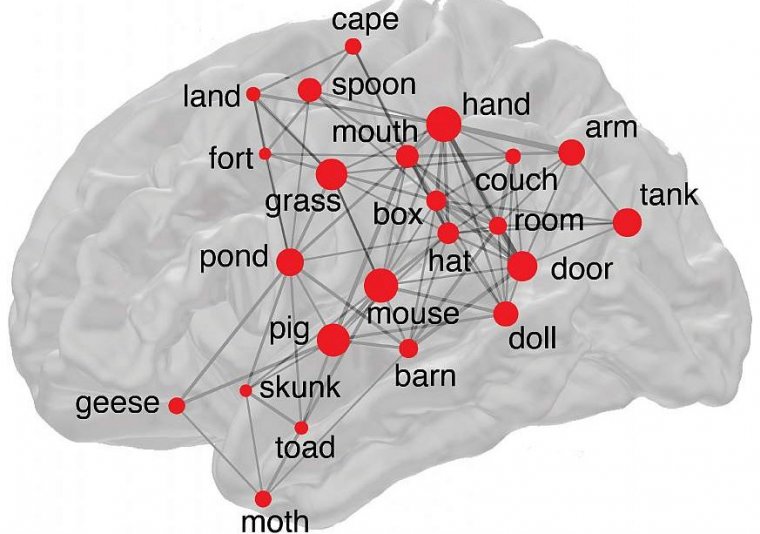

“We thought one way to understand the results of the word pair tests was to apply network theories for how the brain remembers past experiences. In this case, memories of the words we used look like internet or airport terminal maps, with the more memorable words appearing as big, highly trafficked spots connected to smaller spots representing the less memorable words,” said Dr. Xie. “The key to fully understanding this was to figure out what connects the words.”

The researchers found that seemingly straightforward ideas for connecting words could not explain their results. For instance, the more memorable words did not simply appear more often in sentences than the less memorable ones.

Similarly, they could not find a link between the relative “concreteness” of a word’s definition and its memorability. A word like “moth” was no more memorable than a word that has more abstract meanings, like “chief.”

Instead, their results suggested that the more memorable words were more semantically similar, or more often linked to the meanings of other words used in the English language.

This meant, that when the researchers plugged semantic similarity data into the computer model it correctly guessed which words that were memorable from patients and healthy volunteer test. In contrast, this did not happen when they used data on word frequency or concreteness.

Further results supported the idea that the more memorable words represented high trafficked hubs in the brain’s memory networks. The epilepsy patients correctly recalled the memorable words faster than others.

Meanwhile, electrical recordings of the patients’ anterior temporal lobe, a language center, showed that their brains replayed the neural signatures behind those words earlier than the less memorable ones.

The researchers saw this trend when they looked at both averages of all results and individual trials, which strongly suggested that the more memorable words are easier for the brain to find.

Moreover, both the patients and the healthy volunteers mistakenly called out the more memorable words more frequently than any other words.

Overall, these results supported previous studies which suggested that the brain may visit or pass through these highly connected memories, like the way animals forage for food or a computer searches the internet. (National Institutes of Health)